Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

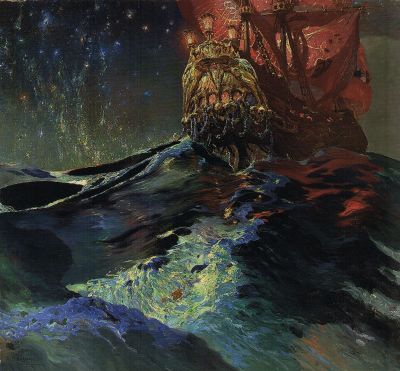

Wojciech Gerson, who found success in Warsaw after studying in St. Petersburg, Warsaw and Paris, and who from 1872 onwards was a professor at the Warsaw drawing school (Klasa rysunkowa), created historical paintings with similar themes to those of Matejko. Like Matejko, he felt that one purpose of art was to fulfil the artist’s “obligations towards their native country” and to communicate “noble ideas” and give expression to “spiritual beauty”.[30] There are three paintings by Matejko on show at the Munich exhibition: “Blind Veit Stoss with his Granddaughter” (1864, Fig. 4 2nd from right), “The Interior of the Tomb of King Kasimir the Great” (1869), and the self-portrait of the artist from the year of his death. All three had been previously included in the Bonn exhibition.[31] The detailed oil on board painting “The Hanging of the Sigismund Bell at the Cathedral Tower in Kraków in 1521”, completed in 1874, is also on display (Fig. 1 ). “Stańczyk” (1862, Fig. 2 ) shows a court jester during a ball at the palace of Sigismund the Elder (1507–1548), who (with Matejko’s own facial features) is shown mulling the political situation of Poland and the future of the country. Gerson is also included in the exhibition with a self-portrait, also a scene referencing Veit Stoss (Fig. 4 right) and with the painting purchased in 2009 from an auction house for the National Museum of Szczecin (Muzeum Narodowe w Szczecinie), “Without Land. Pomeranians, Driven by the Germans to the Baltic Islands” from 1888, which in terms of its composition, motifs and dramatic mood is redolent of “The Raft of the Medusa” (1819) by Théodore Géricault (Fig. 3 ).

As the Munich exhibition understands it, “Silent Rebels” refers above all to the “new generation of young Polish artists” who turned their backs on academic historical painting, challenged patriotism in art and its obligation towards society, and placed artistic freedom at the forefront of their work. This dissent, and the awakening of a new era, are represented at the start of the exhibition by Leon Wyczółkowski, a pupil of Gerson and Matejko, and Matejko’s pupil Malczewski. Their pictorial themes differ greatly from the historical works of their teachers: Wyczółkowski portrays a desperate “Stańczyk” (1898), who has placed members of traditional Polish society on a wall shelf behind him, lined up as a row of dolls. The works by Malczewski – “Painter’s Inspiration” (1897, Fig. 36 ), “Vicious Circle” (1895–1897, Fig. 5 ) and “Painter’s Dream” (around 1888) – depict traditional Polish themes, including the enslaved Polonia, people wearing traditional costumes and prisoners or casualties from former uprisings and wars. They are shown as dreamlike images and ghostly manifestations, and symbolise the rupture experienced by the artist between historical burden and artistic freedom. According to the exhibition room text, Wyczółkowski and Malczewski here represent the “painters of the Young Poland movement”, who established “a new, Symbolist pictorial language”. Here, at the latest, a clear definition of the terms “Symbolism” and “Young Poland” would have been desirable, as well as a differentiation between the two.

In the second section of the exhibition, entitled “Between Paris and St. Petersburg”, Agnieszka Bagińska gives a broad overview of the artists as individuals and the variety of styles of their period (exhibition room text: “In Dialogue with European Art”, Fig. 6 ). Due to the particular political situation characterised in all three divided areas of Poland by more or less severe suppression of Polish culture, Polish artists – in most cases following initial and very thorough training in Kraków and Warsaw – tended to continue their studies in other European art centres, usually in Paris, Munich, Vienna or St. Petersburg, or even to emigrate abroad. They took with them Polish themes and painting styles and developed these further, formed Polish artists’ groups, befriended local artists, were influenced by them, and continued to exhibit their new work in Poland. Thus, Polish art offers a vibrant facet of European artistic development of outstanding quality. As Bagińska rightly concludes: “It is only with a knowledge of a coexistence of and interconnection between different currents that we can obtain a comprehensive and multifarious picture of European art at the turn of the 19th century”.[32]