Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

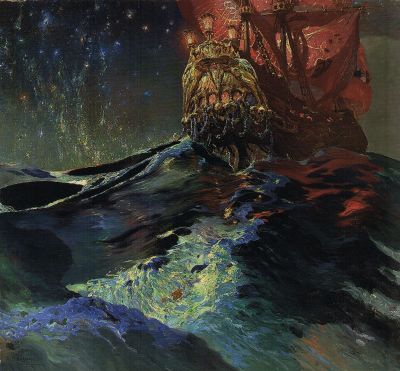

His successor Ferdynand Ruszczyc saw the fragmentation of mankind embodied in the drama and dynamic of nature. In his paintings, he pursued a “pictorial vision of Earth”[36] and symbolised the uncontrollability of nature. The obvious proximity of his painting “The Cloud” (1902, Fig. 13

To date, childhood and youth have hardly been acknowledged at all as a separate theme in European Symbolism, although there is sufficient evidence in favour of doing so. While since the early industrial period, children had been brought up as small adults in bourgeois circles, or out of simple necessity were maltreated as work slaves within the poorer levels of society, at the turn of the 20th century, childhood was perceived as being a separate phase in life, with youth as the flourishing of life. Finally, the Lebensreform movement (Fidus: “Light Prayer”, 1913) viewed children as powerful figures of light. This change in attitude is also reflected in numerous Symbolist works. In Hans von Marées work showing “Life Ages” (1873/74), children play a central role. Puvis de Chavannes had crowds of children playing naked and outdoors with sheep in the presence of their mothers (“Summer”, 1873). For Elisabeth Sonrel, they became a symbol of blossoming life (“Procession of Flora”, 1897), and Maurice Denis also rarely passed up on an opportunity to include children in his pictorial scenes (“Holy Women at the Tomb”, 1894). Magnus Enckell depicted a naked boy pondering over a skull as a symbol of human fate (1892). In Max Klinger’s and Edvard Munch’s works, children sit or stand at the bed of their dead mother, or for Walter Crane are mown down by the “Reaper” (1900/09). Jens Willumsen shows a boy running under a blazing sun after his anguished mother, whose husband has died a seaman’s death (“After the Tempest”, 1905). For Segantini, children in a tree symbolise the “Angel of Life” or the “Child Murderer” (both 1894). Young adults at the crossroads between innocence and awakening sensuality are portrayed by Franz von Stuck (“Innocentia”, 1889) and Ferdinand Hodler (“Spring”, 1901). “The Strange Garden” (1903) by the Polish artist Józef Mehoffer, which is displayed and acknowledged early on in the exhibition has given rise to various different interpretations of the naked boy with raised hollyhock stems: from Puck in a Polish “Midsummer Day’s Dream”[39] to the “notion of a carefree existence far removed from all time and civilisation”, as Godetzky writes in the fourth contribution to the Munich catalogue in an essay entitled “Street Children of the Atelier”.[40]

To the credit of the Munich exhibition, it dedicates an entire section to this topic (exhibition room text: “Spring Awakening”), filling it with works from Polish museums that are rarely shown (Fig. 14 ). Similarly to the Symbolist works from other European countries which associate childhood and youth with themes such as “innocence, purity, incorruptibility, new beginnings, life force, religious piety, the natural world and, above all, spring”,[41] Wojciech Weiss showed a youthful figure at the threshold between childhood and sexual awakening (“Springtime”, 1898, Fig. 15 ), while in the background, naked adults chase each other in the open fields. During this same period, Weiss studied the writings of Przybyszewski, in which he discussed sexual awakening and erotic desire as the real impulses for tensions within society.[42] Malczewski portrays himself as a satyr with cloven hoofs, abducting two street urchins (“My Models”, 1897, Fig. 16 ) into the realm of fantasy, surreal dreams and creativity on the path leading to his atelier. This atelier, according to reports by the contemporary writer and art critic Konstanty Górski, was “a place of libertinism and frivolity”[43]. Malczewski’s pupil Wlastimil Hofman depicted “Spring” (1918, Fig. 14 left centre) as a childlike faun or satyr, a typical creature from the Symbolist world of Arnold Böcklin,[44] thus portraying childhood as a time of uncontrolled, unpredictable animalist impulses.

[36] Ibid., page 80

[37] Prince Eugen: Cloud/Molnet, 1896, oil on canvas, 119 x 109 cm, Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde, Stockholm, https://collection-pew.zetcom.net/sv/collection/item/82416/

[38] Kozakowska-Zaucha 2022 (see note 35), page 82

[39] Symbolismus in Europa 1976 (see note 8), page 128

[40] Albert Godetzky: Straßenkinder des Ateliers. Jugend und Kindheit als Sujets in der polnischen Malerei um 1900, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 112. Godetzky refers to Agnieszka Morawińska: Hortus deliciarum Józefa Mehoffera, in: Ars auro prior. Studia Ioanni Białostocki sexagenario dicata, published by Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Warsaw 1981, page 713–718

[41] Godetzky 2022 (see note 40), page 111

[42] Ibid., page 110

[43] Ibid., page 115

[44] Arnold Böcklin: Faun Whistling to a Blackbird, 1864/65. Oil on canvas, 48.8 x 49 cm, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover