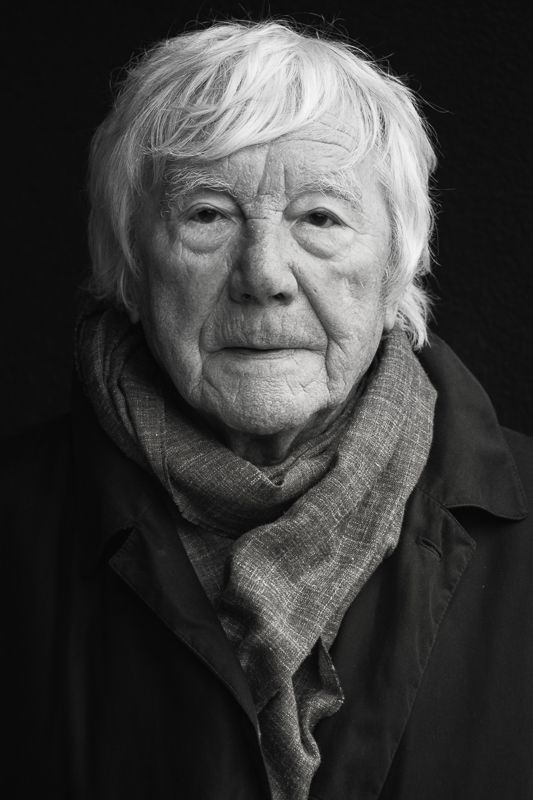

Tadeusz Rolke. A master of documentary photography

Mediathek Sorted

“I will travel and take photographs.”

These were the words spoken in 1944 by the 15-year-old Tadeusz Rolke. They would not have been particularly remarkable but for the circumstances in which they were uttered. During that time, the young Tadeusz was working as a forced labourer on the farm of the Gensch family in Dobbrikow in Brandenburg. Due to his delicate physique and young age, his German employers were dissatisfied with the amount of work he completed every day. These words, which would later become his life motto as an adult, were the answer he gave to the farmer’s wife when she asked him what he wanted to do with his life since he wasn’t fit for hard physical work.[1]

Tadeusz Rolke, who was born in Warsaw on 24 May 1929, and who was brought up to be independent even as a child, already took an interest in photography early on. At 14, he bought his first camera, a “Kodak BabyBox”, from a schoolfriend, which he paid for by selling model aeroplanes that he had made himself. After the death of his father, an administrative director in the city hall in Warsaw, the family fell on hard times. Together with his older brother Andrzej, Tadeusz attended the Helena Chełmońska school until it was closed following the outbreak of the Second World War. He continued his education by taking lessons given in private homes where students and teachers met in secret. Describing his experiences at the start of the war, he says:

“The most frightened I have ever been in my life was when I heard the aeroplanes coming and the bombs falling closer and closer. On 24 and 25 September 1939, there were devastating air attacks on Warsaw. We sought shelter in a cellar (...). After two days, we no longer recognised the street where we lived [the family lived in Nowy Świat street – author’s note]. In front of us was a corridor of burning houses. It was in the middle of the day, yet there was complete darkness.”[2]

During the war, the 12-year-old Tadeusz joined the Szare Szeregi (Grey Ranks), an underground Polish scouting organisation. There, he learned typical scout skills, but also how to shadow people, deliver prohibited printed materials and conduct small acts of sabotage. The outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising, on 1 August 1944, took Rolke by surprise after he travelled by bike to a scouts meeting in Wilanów [a district of Warsaw – translator’s note]. When he tried to return to the city centre, he was shot in the thigh. At the end of August, he began work as a courier. From then on, he delivered messages and helped recover the bodies of soldiers that had been buried in the rubble during the bombing raids. Looking back, Tadeusz Rolke is critical of the Warsaw Uprising. The order issued by Tadeusz Komorowski, codename “Bór”, to rise up against the incomparably better armed, battle-trained enemy was, in Rolke’s view, a crime of enormous magnitude which unnecessarily put the lives of the population of Warsaw at risk.[3] He has a similar view of the lofty patriotic mood that prevailed among his fellow Szare Szeregi members:

“The scout movement was strongly Catholic; no-one spoke about the Jews. I never heard one word about the Jews in the Szare Szeregi, either. They didn’t exist. There was no ghetto. There was no uprising in the ghetto. They didn’t exist.”[4]

Rolke also addresses this topic in his book “Moja namiętność” (My Passion):

“They were oblivious to everything except God, honour, the fatherland (...). No word was spoken about this. For the ‘Szare Szeregi’ there simply were no three million Jews. Evidently, this attitude was rooted in antisemitism as well as in Polish Catholicism and nationalism.”[5]

When the pockets of resistance increased in number at the start of September 1944, Rolke was interned in transit camp no. 121 in Pruszków. From there, he was sent to Germany as a forced labourer. From the transit camp in Frankfurt/Oder, he was taken to a farm owned by the Gensch family in Dobbrikow, Brandenburg, about 50 km to the south of Berlin. Despite the hard physical work in the fields, Rolke has fond memories of this time. Like the other forced labourers, he had his own room, and was given the same food to eat as the farmer’s family. He sat at the table with them. After witnessing the poverty that was rife in the Polish countryside, the level of productivity on the farm in Dobbrikow and the affluence enjoyed by his employers came as a cultural shock. Rolke attributes the humane way in which the forced labourers were treated to the inevitable approach of defeat in the war, of which the German population was becoming increasingly aware at that time.

Taduesz Rolke spent just a few weeks with the Gensch family before the Germans moved him and the other forced labourers to Chwalim, now in the Lubusz voivodeship (woj. lubuskie) in November 1944. They travelled there via Berlin, which Rolke saw for the first time. Years later, he had no qualms about saying that he found a kind of pleasure at the sight of the destroyed city with its empty streets, the endless rows of burned-out houses and the ruins everywhere. In Chwalim, the labourers were made to dig tank ditches in order to delay the approaching Russian offensive. Next, the men were sent to Szczutowo, near Sierpc, and from there, they marched on foot to the town of Golub (Gollub), just behind the front. In March 1945, Rolke arrived in Gdańsk (Danzig), which had already been encircled by the Red Army. Shortly afterwards, the Russians entered the city. Tadeusz, now 16 years old, was finally free and able to return to Warsaw. There, he was reunited with his mother. At that time, his older brother was in a displaced persons camp in Maczków, in a Polish enclave in Lower Saxony in Germany. It would be two years before he returned home. For Tadeusz, however, the joy over the end of the war and the opportunity to resume his former life was mingled with disappointment at the new geopolitical situation in his home country. Watching the victory parade of the Soviet soldiers on 9 May 1945, he realised that Poland’s situation as an occupied country had gone from bad to worse.

[1] https://culture.pl/pl/tworca/tadeusz-rolke (last accessed: 8/1/2021).

[2] “Tadeusz Rolke. Moja namiętność. Mistrz fotografii w rozmowie z Małgorzatą Purzyńską” [Tadeusz Rolke. My Passion. The Master of Photography in Conversation with Małgorzata Purzyńska], Agora SA, Warsaw 2016, p. 28–29.

[3] “Tadeusz Rolke. Moja namiętność”, p. 36.

[4] Mirosław Tkaczyk, “Drzazga. Kłamstwa silniejsze niż śmierć”, Znak Literanova, Kraków 2020.

[5] “Tadeusz Rolke. Moja namiętność”, p. 33.