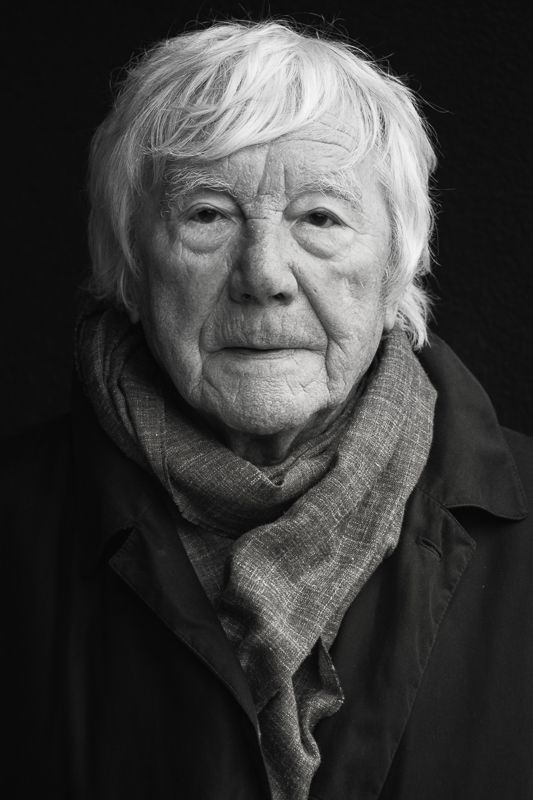

Tadeusz Rolke. A master of documentary photography

Mediathek Sorted

After the war, Tadeusz Rolke returned to school, and to taking photographs. He documented the destroyed city of Warsaw and the places where he had grown up before the war. Dozens of these photographs have been preserved. He travelled around Poland with increasing frequency, photographing people, towns and cities. In 1950, he enrolled as a student of philosophy and art history at the Catholic University of Lublin (Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski). Soon afterwards, he switched to his dream university in Warsaw, where he continued his art history studies. However, his streak of good luck didn’t last for long. In 1952, he was arrested and accused of being a member of Ruch Uniwersalistów (the Universalist movement), an organisation designated as illegal and hostile to the state by the government of the People’s Republic of Poland. The investigators found his name in a notebook belonging to Władysław Jaworski, the alleged leader of the movement. In a conversation with the Polish press agency (Polska Agencja Prasowa) in connection with an exhibition in Budapest in 2019, he described this period as follows:

“Without the terror overall, there would have been no Stalinism. The political police smelled danger in every meeting, particularly among young people. Władysław Jaworski had just graduated from the SGH (the trade and commerce college in Warsaw). In his diploma thesis, he criticised both the capitalist and socialist economic systems. He demanded a system somewhere in the middle: economic universalism. The thesis came to the notice of the SB (the Polish security service) and was classified as subversive material which compromised the basic order of the People’s Republic. All the people whom Jaworski knew from his wide circle of social contacts were arrested. All of them were branded as members of the illegal ‘Universalist movement’.”[6]

Rolke was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for anti-state activity and ownership of subversive texts. In September 1954, he was released as part of an amnesty. However, there was no longer any question of the politically convicted “enemy of the people” being able to continue his studies. Tadeusz Rolke turned instead to professional photography, and took up work as an untrained assistant in the photo laboratory of the Polish optics company Polskie Zakłady Optyczne, where he spent his evenings after work exploring the secrets of photography in the darkroom. In 1955, he joined the Zakład Foto-Przeźroczy [a state-run company producing slides – translator’s note] as a photographer. He went on many trips across Poland, taking photographs mainly of the agriculture and food industries. During this time, it became increasingly clear to him that he wanted to become a journalist. Finally, he was offered the chance to work with the most popular scouting journal, “Świat Młodych” (Youth World) and the illustrated weekly magazine “Stolica” (The Capital). Rolke’s talent was quickly recognised. Not only that, the “thaw” was breaking out in Poland at that time, thanks to which the legal convictions of the past no longer acted as an obstacle to his career path. Regular employment as a photojournalist was now within reach. In 1956, Rolke was offered a permanent job at “Stolica”, a magazine devoted to the reconstruction of Warsaw. Rolke recorded everyday life in the city, photographing architects, artists and painters, and occasionally also Party dignitaries. In 1960, he moved to a new job at the monthly journal “Polska”, which was published in several languages, and also worked for the weekly publication “Przekrój” (Profile) and the magazine “Ty i ja” (You and Me). He also took on fashion photography work, collaborating with the designer Barbara Hoff and later with Grażyna Hase. However, he didn’t regard himself as a fashion photographer:

“At that time, you had to be flexible. I was never a fashion photographer, which is why I never photographed models on the runway, in other words, women who are reduced to walking clothes hangers. I enjoyed photographing fashion. I gave the models a lot of leeway. They behaved very naturally in front of my lens and my job was to create a unique atmosphere.”[7]

Rolke’s fashion photographs were taken in Warsaw, Paris and Moscow.

However, despite his career success, he found it increasingly difficult to cope with the grey, repressive nature of everyday life in the People’s Republic of Poland during the 1960s. Not only that, but Rolke also awakened the interest of the state security service due to his contacts with foreign journalists. In a state-controlled reality, it was difficult to develop and pursue his own goals. The final straw came in 1968, when the Polish government began harassing the Jews living in Poland, while the Polish army became involved in the intervention in Czechoslovakia. Rolke decided to put his idea of emigrating to the West into action. Despite efforts to help him by his contacts abroad, his passport applications were turned down every time. Finally, in 1970, he was able to leave the country when he received a grant from Aktion Sühnezeichen (Action for Peace and Reconciliation), for which he had already taken photographs documenting the work of young Germans in the former concentration camp in Auschwitz. He moved to Wolfsburg, where he prepared his first photography exhibition, “Väter und Kinder” (Fathers and Children), which showed images from the concentration camp, both of the fathers, who were there for an on-site gathering as part of an Auschwitz trial, and of the children, who were working as volunteers there for Aktion Sühnezeichen. The photographs were exhibited again in Germany in 2011, this time as part of the exhibition “Tür an Tür. Polen – Deutschland. 1000 Jahre Kunst und Geschichte” (Door to Door. Poland – Germany. 1,000 Years of Art and History) in the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin.

[6] Quoted from the article “W Budapeszcie wystawa zdjęć Tadeusza Rolkego” on the dzieje.pl portal: https://dzieje.pl/wystawy/w-budapeszcie-wystawa-zdjec-tadeusza-rolkego (last accessed: 11/01/2021).

[7] “Tadeusz Rolke. Moja namiętność”, p. 171.