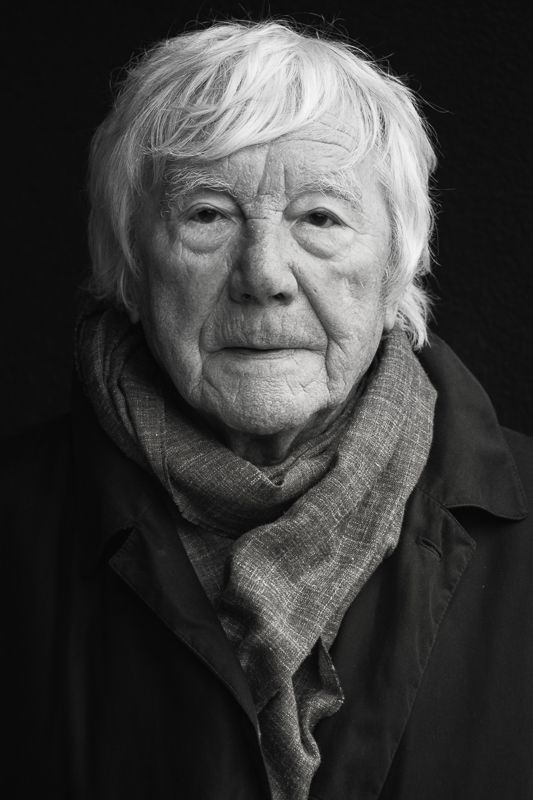

Tadeusz Rolke. A master of documentary photography

Mediathek Sorted

“I will travel and take photographs.”

These were the words spoken in 1944 by the 15-year-old Tadeusz Rolke. They would not have been particularly remarkable but for the circumstances in which they were uttered. During that time, the young Tadeusz was working as a forced labourer on the farm of the Gensch family in Dobbrikow in Brandenburg. Due to his delicate physique and young age, his German employers were dissatisfied with the amount of work he completed every day. These words, which would later become his life motto as an adult, were the answer he gave to the farmer’s wife when she asked him what he wanted to do with his life since he wasn’t fit for hard physical work.[1]

Tadeusz Rolke, who was born in Warsaw on 24 May 1929, and who was brought up to be independent even as a child, already took an interest in photography early on. At 14, he bought his first camera, a “Kodak BabyBox”, from a schoolfriend, which he paid for by selling model aeroplanes that he had made himself. After the death of his father, an administrative director in the city hall in Warsaw, the family fell on hard times. Together with his older brother Andrzej, Tadeusz attended the Helena Chełmońska school until it was closed following the outbreak of the Second World War. He continued his education by taking lessons given in private homes where students and teachers met in secret. Describing his experiences at the start of the war, he says:

“The most frightened I have ever been in my life was when I heard the aeroplanes coming and the bombs falling closer and closer. On 24 and 25 September 1939, there were devastating air attacks on Warsaw. We sought shelter in a cellar (...). After two days, we no longer recognised the street where we lived [the family lived in Nowy Świat street – author’s note]. In front of us was a corridor of burning houses. It was in the middle of the day, yet there was complete darkness.”[2]

During the war, the 12-year-old Tadeusz joined the Szare Szeregi (Grey Ranks), an underground Polish scouting organisation. There, he learned typical scout skills, but also how to shadow people, deliver prohibited printed materials and conduct small acts of sabotage. The outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising, on 1 August 1944, took Rolke by surprise after he travelled by bike to a scouts meeting in Wilanów [a district of Warsaw – translator’s note]. When he tried to return to the city centre, he was shot in the thigh. At the end of August, he began work as a courier. From then on, he delivered messages and helped recover the bodies of soldiers that had been buried in the rubble during the bombing raids. Looking back, Tadeusz Rolke is critical of the Warsaw Uprising. The order issued by Tadeusz Komorowski, codename “Bór”, to rise up against the incomparably better armed, battle-trained enemy was, in Rolke’s view, a crime of enormous magnitude which unnecessarily put the lives of the population of Warsaw at risk.[3] He has a similar view of the lofty patriotic mood that prevailed among his fellow Szare Szeregi members:

“The scout movement was strongly Catholic; no-one spoke about the Jews. I never heard one word about the Jews in the Szare Szeregi, either. They didn’t exist. There was no ghetto. There was no uprising in the ghetto. They didn’t exist.”[4]

Rolke also addresses this topic in his book “Moja namiętność” (My Passion):

“They were oblivious to everything except God, honour, the fatherland (...). No word was spoken about this. For the ‘Szare Szeregi’ there simply were no three million Jews. Evidently, this attitude was rooted in antisemitism as well as in Polish Catholicism and nationalism.”[5]

When the pockets of resistance increased in number at the start of September 1944, Rolke was interned in transit camp no. 121 in Pruszków. From there, he was sent to Germany as a forced labourer. From the transit camp in Frankfurt/Oder, he was taken to a farm owned by the Gensch family in Dobbrikow, Brandenburg, about 50 km to the south of Berlin. Despite the hard physical work in the fields, Rolke has fond memories of this time. Like the other forced labourers, he had his own room, and was given the same food to eat as the farmer’s family. He sat at the table with them. After witnessing the poverty that was rife in the Polish countryside, the level of productivity on the farm in Dobbrikow and the affluence enjoyed by his employers came as a cultural shock. Rolke attributes the humane way in which the forced labourers were treated to the inevitable approach of defeat in the war, of which the German population was becoming increasingly aware at that time.

Taduesz Rolke spent just a few weeks with the Gensch family before the Germans moved him and the other forced labourers to Chwalim, now in the Lubusz voivodeship (woj. lubuskie) in November 1944. They travelled there via Berlin, which Rolke saw for the first time. Years later, he had no qualms about saying that he found a kind of pleasure at the sight of the destroyed city with its empty streets, the endless rows of burned-out houses and the ruins everywhere. In Chwalim, the labourers were made to dig tank ditches in order to delay the approaching Russian offensive. Next, the men were sent to Szczutowo, near Sierpc, and from there, they marched on foot to the town of Golub (Gollub), just behind the front. In March 1945, Rolke arrived in Gdańsk (Danzig), which had already been encircled by the Red Army. Shortly afterwards, the Russians entered the city. Tadeusz, now 16 years old, was finally free and able to return to Warsaw. There, he was reunited with his mother. At that time, his older brother was in a displaced persons camp in Maczków, in a Polish enclave in Lower Saxony in Germany. It would be two years before he returned home. For Tadeusz, however, the joy over the end of the war and the opportunity to resume his former life was mingled with disappointment at the new geopolitical situation in his home country. Watching the victory parade of the Soviet soldiers on 9 May 1945, he realised that Poland’s situation as an occupied country had gone from bad to worse.

After the war, Tadeusz Rolke returned to school, and to taking photographs. He documented the destroyed city of Warsaw and the places where he had grown up before the war. Dozens of these photographs have been preserved. He travelled around Poland with increasing frequency, photographing people, towns and cities. In 1950, he enrolled as a student of philosophy and art history at the Catholic University of Lublin (Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski). Soon afterwards, he switched to his dream university in Warsaw, where he continued his art history studies. However, his streak of good luck didn’t last for long. In 1952, he was arrested and accused of being a member of Ruch Uniwersalistów (the Universalist movement), an organisation designated as illegal and hostile to the state by the government of the People’s Republic of Poland. The investigators found his name in a notebook belonging to Władysław Jaworski, the alleged leader of the movement. In a conversation with the Polish press agency (Polska Agencja Prasowa) in connection with an exhibition in Budapest in 2019, he described this period as follows:

“Without the terror overall, there would have been no Stalinism. The political police smelled danger in every meeting, particularly among young people. Władysław Jaworski had just graduated from the SGH (the trade and commerce college in Warsaw). In his diploma thesis, he criticised both the capitalist and socialist economic systems. He demanded a system somewhere in the middle: economic universalism. The thesis came to the notice of the SB (the Polish security service) and was classified as subversive material which compromised the basic order of the People’s Republic. All the people whom Jaworski knew from his wide circle of social contacts were arrested. All of them were branded as members of the illegal ‘Universalist movement’.”[6]

Rolke was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for anti-state activity and ownership of subversive texts. In September 1954, he was released as part of an amnesty. However, there was no longer any question of the politically convicted “enemy of the people” being able to continue his studies. Tadeusz Rolke turned instead to professional photography, and took up work as an untrained assistant in the photo laboratory of the Polish optics company Polskie Zakłady Optyczne, where he spent his evenings after work exploring the secrets of photography in the darkroom. In 1955, he joined the Zakład Foto-Przeźroczy [a state-run company producing slides – translator’s note] as a photographer. He went on many trips across Poland, taking photographs mainly of the agriculture and food industries. During this time, it became increasingly clear to him that he wanted to become a journalist. Finally, he was offered the chance to work with the most popular scouting journal, “Świat Młodych” (Youth World) and the illustrated weekly magazine “Stolica” (The Capital). Rolke’s talent was quickly recognised. Not only that, the “thaw” was breaking out in Poland at that time, thanks to which the legal convictions of the past no longer acted as an obstacle to his career path. Regular employment as a photojournalist was now within reach. In 1956, Rolke was offered a permanent job at “Stolica”, a magazine devoted to the reconstruction of Warsaw. Rolke recorded everyday life in the city, photographing architects, artists and painters, and occasionally also Party dignitaries. In 1960, he moved to a new job at the monthly journal “Polska”, which was published in several languages, and also worked for the weekly publication “Przekrój” (Profile) and the magazine “Ty i ja” (You and Me). He also took on fashion photography work, collaborating with the designer Barbara Hoff and later with Grażyna Hase. However, he didn’t regard himself as a fashion photographer:

“At that time, you had to be flexible. I was never a fashion photographer, which is why I never photographed models on the runway, in other words, women who are reduced to walking clothes hangers. I enjoyed photographing fashion. I gave the models a lot of leeway. They behaved very naturally in front of my lens and my job was to create a unique atmosphere.”[7]

Rolke’s fashion photographs were taken in Warsaw, Paris and Moscow.

However, despite his career success, he found it increasingly difficult to cope with the grey, repressive nature of everyday life in the People’s Republic of Poland during the 1960s. Not only that, but Rolke also awakened the interest of the state security service due to his contacts with foreign journalists. In a state-controlled reality, it was difficult to develop and pursue his own goals. The final straw came in 1968, when the Polish government began harassing the Jews living in Poland, while the Polish army became involved in the intervention in Czechoslovakia. Rolke decided to put his idea of emigrating to the West into action. Despite efforts to help him by his contacts abroad, his passport applications were turned down every time. Finally, in 1970, he was able to leave the country when he received a grant from Aktion Sühnezeichen (Action for Peace and Reconciliation), for which he had already taken photographs documenting the work of young Germans in the former concentration camp in Auschwitz. He moved to Wolfsburg, where he prepared his first photography exhibition, “Väter und Kinder” (Fathers and Children), which showed images from the concentration camp, both of the fathers, who were there for an on-site gathering as part of an Auschwitz trial, and of the children, who were working as volunteers there for Aktion Sühnezeichen. The photographs were exhibited again in Germany in 2011, this time as part of the exhibition “Tür an Tür. Polen – Deutschland. 1000 Jahre Kunst und Geschichte” (Door to Door. Poland – Germany. 1,000 Years of Art and History) in the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin.

Thanks to the grant, Rolke was able to visit Germany again for the first time since 1945. Above all, however, this was his first visit to West Germany (during the war he had only been in the east – author’s note). He was very impressed by the level of affluence visible everywhere:

“There was an enormous difference in the kind of civilisation between the two countries at that time. This standard of living and the shops... There was no comparison. In a word: the Germans had won the war, and Poland had lost. That was my conclusion.”[8]

Rolke decided not to return to Poland after the grant expired. His first commissions were for film productions, where he created portraits of the actors and took photographs on set. Later, he moved to Hamburg, where he worked for a short time as an employee of the Heinrich Bauer Verlag publishing house. He later became a freelancer, taking photos of Hamburg artists for various different companies. During this time, he produced his first photo essays, which were published in the press. Rolke also travelled around the country and took up work for Inter Nationes, a government-run agency in Bonn whose tasks included cultural PR work for the Federal Republic of Germany. He took portraits of major West German artists, including the painter Gerhard Richter, the painter and “Happening” artist Wolf Vostell and the versatile Joseph Beuys. The photograph of Beuys leaning against the hood of a VW Beetle is one of Rolke’s most famous images.

During this period, the turbulence in Poland during the 1970s, the growing protests against the government and the repressive measures against the “intransigents” engendered an increased interest in the country and its people. Rolke’s coverage appeared in the most popular West German magazines, from “Stern”, “Die Zeit” and “Der Spiegel” to “GEO”. His photographs of the famous Hamburg fish market attracted a great deal of attention. Rolke succeeded like no-one else in capturing the unique mixture of the bustle of the fish market and the colourful life that also played an important role there. The photographs of the fish market were also Rolke’s largest photo essay. He later remembered the market as follows:

“The air at this market pulsed with very interesting social activities. Visiting it was like going on a hunt. It was always really exciting to wonder how many pictures I would take over the course of the day. By the afternoon, I would already know: five photos are a good day. (...) I was fascinated by the way the people behaved, by their interactions and their diversity, by the bars, the whole relaxed atmosphere. It was like being in a cauldron.”[9]

While he was living in Germany, he was able to visit Poland multiple times, although not before having to wait several years to obtain a passport. In Poland, a “Solidarność carnival” was in full swing. An independent press was emerging, the communist regime was showing signs of becoming more liberal, and the government was allowing its citizens greater freedoms. During this period, Rolke produced a large feature for “Stern” magazine and others on the “Solidarność” conference held at the Warsaw University of Technology (Politechnika Warszawska). However, the thaw in Poland didn’t last long. It ended with the imposition of martial law on 13 December 1981. Rolke heard the news at the fish market in Hamburg. Several days later, he decided to return to Poland. There, he took almost no photographs, saying that he did not regard himself as a political photographer. At this time, inspired by “The Art of Loving” by Erich Fromm, he worked on an album about love, although this was never published. He now worked for the German art journal “Art” and published his reports from Poland in the “GEO”, Stern” and “Brigitte” magazines.

In Poland, Rolke became known above all as a chronicler of everyday life and social change, which he witnessed over a period of decades. His most important exhibition on these topics was “Jutro będzie lepiej” (It’ll get better tomorrow) in 2011. The exhibition showed photographs documenting the political upheaval during 1989 and the early 1990s. The images clearly demonstrate his talent for choosing the right moment. Like almost no-one else, Rolke is able to seek out the extraordinary in everyday life. He is a master of recording short moments for posterity that other people failed to notice. His oeuvre also includes outstanding portraits of Polish artists such as Tadeusz Kantor, the painter Nikifor, Kora Jackowska, the frontwoman in the band “Maanam”, Alina Szapocznikow, Zbigniew Cybulski and Kalina Jędrusik.

From the 1990s onwards, Tadeusz Rolke, who by now was no longer a member of any editorial team, devoted himself with increasing passion to his own projects – including the search for traces of Jewish life in Poland and Ukraine. He explains his reasons for doing so:

“I was a witness, after all. I really saw the Holocaust; I didn’t just read or hear about it. And I wanted to talk about it. I want to do it publicly, and not behind closed doors. In some way, this was also a personal mission of mine.”[10]

In 2008, the Berlin-based publishing house edition.fotoTAPETA, which Rolke had co-founded, published the album “Wir waren hier. Verschwindende Spuren einer verschwundenen Kultur” (We were Here. The Vanishing Traces of a Vanished Culture) which shows images of the remnants of Hassidic culture in the former Polish territories. In turn, the theme of the obscured past was addressed in the project “Sąsiadka” (The Neighbour). The inspiration for the project came from a book by the historian Jan Tomasz Gross, “Sąsiedzi. Historia zagłady żydowskiego miasteczka” [English: Neighbors. The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, Princeton University Press, 2001 – translator’s note]. The book tells the story of the Jews in Jedwabne, who were murdered by their Polish neighbours in 1941. Rolke curated the exhibition together with the photographer Chris Niedenthal. The exhibition was opened in 2001 to mark the 60th anniversary of the date when the events took place. In 2017, Rolke returned to this theme, travelling to 16 locations where similar pogroms were carried out, as documented by Mirosław Tryczyk in his book “Miasta śmierci” (Death Towns). The exhibition “Lekcja pamięci” (Lesson in Remembrance) was shown at the Jewish Historical Institute (Żydowski Instytut Historyczny) in Warsaw.

Of particular importance within Tadeusz Rolke’s work as a whole is the “Tam i z powrotem” (There and Back) project from 2019. It takes the 90-year-old photographer back to the places where he spent time at the end of the war. As part of the project, he travelled around Poland and Germany for ten days, producing over 20 photographs that tell the story of his life as a boy and young man. We see the village of Dobbrikow in Brandenburg as it looks today, where the young Rolke worked as a forced labourer, as well as Berlin, Kargowa, Chwalim, Okonin and, finally, Gdańsk. Marek Grygiel, the curator of the exhibition, which was shown at the Warsaw gallery “La Guern” in honour of Rolke’s 90th birthday, describes the project as follows:

“The idea of re-living this journey 75 years later is a reminder of the formative years in the life of the young boy. Considering the fact that each place along the road looks entirely different today, it wasn’t an easy journey to make. The images stored away in memory for many years come back to life; memories return and stand the test of time. The photographs, which were taken over a period of just ten days and after 2,200 km on the road, represent both the real and geographical places where events took place many years ago. But they also portray places that refer directly to the dramatic period in Tadeusz Rolke’s life.”[11]

Tadeusz Rolke continues to work despite his advanced age, and galleries are still keen to show his works. He just about always has a camera to hand. He is regarded as a true phenomenon among the viewing public and photography critics. In his foreword to the album “Tadeusz Rolke. Fotografie 1944–2005”, Adam Szymczyk wrote:

“He belongs to the dying generation of artists who believe in the value of photography, which lies in the recording of a moment of disclosure. Intuitively and intelligently, he always manages to be present where the planets align, and to capture this on camera. It is thanks to artists such as him that miracles still happen, and the purpose of memory is to enable us to have something that we can forget. Without him, we would be living in an eternal, perfectly transparent present, like on television.”[12]

Monika Stefanek, January 2021

Photographs shown with the kind permission of Tadeusz Rolke and Agencja Gazeta

Recent photo albums:

- “Rolke” (2015) http://www.bosz.com.pl/books/496/Rolke-Tadeusz-Rolke/-

- “Rolke w kolorze” (2019) http://www.bosz.com.pl/books/693/Rolke-w-kolorze-Tadeusz-Rolke/d,53,10/

A film directed by Piotr Stasik on the life of Tadeusz Rolke was released in 2012, entitled “Dziennik podróży” (The Travel Diary): https://ninateka.pl/film/dziennik-z-podrozy-piotr-stasik