Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

In 1967, the art historian and professor of aesthetics Renato Barilli, who taught in Bologna, described Symbolism as a cultural movement which began in France during the 1880s and 1890s in the literature of Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud and Mallarmé, while its first manifesto was written by Jean Moréas in the literary supplement to the “Figaro” newspaper in the autumn of 1886. According to Moréas, Symbolism wanted to give the “idea” a form. Charles Morice added that the aim was to achieve a reconciliation between the spirit and the senses, of truth and beauty, faith and joy, science and art, and not least to create “a fruitful alliance between the natural sciences and metaphysics”.[6] In painting, Barilli recognised the “idealists” Puvis de Chavannes and Moreau as being forerunners, traced the beginnings of Symbolism back to Carrière and Redon, and then created a broad arc covering Seurat, Gauguin, Bernard and the Pont-Aven school, van Gogh and the Nabis through to Art Nouveau with Toulouse-Lautrec, Mucha and Grasset.

In his book “Symbolist Art”, published in London in 1972, the art critic Edward Lucie-Smith traced the British Symbolist movement back to the Romantic period, with William Blake and the Pre-Raphaelites Millais, Holman Hunt and Rossetti. However, he also located the true origins of Symbolism in French literature, particularly in Joris-Karl Huysmans, who was inspired by the paintings of Moreau and Redon to explore the themes of decadence and Satanism in his novels “À rebours” (1884) and “Là-bas” (1891). According to Lucie-Smith, Mallarmé, by contrast, derived his understanding of the world from the ambiguous nature of its phenomena and symbols, as well as from astrological and alchemistic ideas, in order to ultimately create a new reality that was at peace with itself.[7]

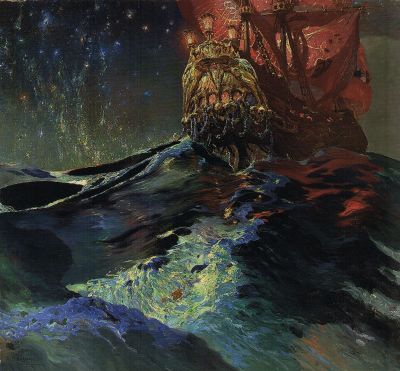

The “Symbolism in Europe” exhibition showed over 260 works of art from 15 countries, including Poland. The subjects of the works, nearly all of which were figural, were selected based on their depiction of the “imaginative images and forms” according to Moréas’ definition, “in which the ambiguous nature and polymorphism of the idea ... are combined”: “The search for the hidden purpose and the secret meaning in the ‘appearance of the real’ brought the Symbolists to more or less adventurous ‘journeys of exploration’ through space and time, to excavations in the underground caverns of the unconscious [...] The symbolists attempted to discern the spiritual message from the everyday and to show it, not in a natural light, but in the aureole of a revelation.”[8] Hofstätter added that: “The Symbolists also attempted to do what Christianity had undertaken from the beginning: to provide a sense of meaning for our world by imagining a world beyond, and to offer hope for liberation and release from its hardships.”[9] In the exhibition, Polish art was represented by Jacek Malczewski (“Whirlwind”, today: “In the Dust Storm”, 1893–1895, Fig. 18

In Poland, art history research had developed terms to describe art periods that differed from those used in western Europe. Overall, there is a tendency to distil the period around the turn of the 20th century into a single term. In the catalogue published in 1984 to accompany the exhibition “Symbolism in Polish Painting 1890–1914” at the Detroit Institute of Arts (which was reproduced in 1987 in Polish in the Warsaw National Museum’s annual volume), Agnieszka Morawińska argued that the terms “Fin de Siècle” or “Belle Époque” had proven to be too narrow. Finally, it was agreed that the historical term “Young Poland/Młoda Polska” should be used; alternatively, preference was given to the term “Modernizm” used by Sven Lövgren[10], which was rendered into Polish from the original English. According to Morawińska, however, “Modernizm” was also unsuitable, since outside of Poland, the term was increasingly used to describe “the experimental art of the 20th century”[11]. The people responsible for creating the concept for the exhibition in Detroit were certainly aware of the narrower definition of Symbolism coined by Hofstätter based on Moréas’ ideas, as well as of the “Symbolism in Europe” exhibition. Even so, according to Morawińska, when describing the epoch of Polish “thought painting”, or “idea painting/Malarstwo myśli”, which covered a broader spectrum of content, the decision was made to use the word “Symbolism” in relation to the period after Matejko so as not to further exacerbate the terminological chaos.

[6] Renato Barilli: Symbolismus [Milan 1967], Munich 1975, page 8

[7] Edward Lucie-Smith: Symbolist Art, London: Thames and Hudson 1972, page 51–55

[8] Franco Russoli: Bildvorstellungen und Darstellungsformen des Symbolismus, in: Symbolismus in Europa, exhibition catalogue Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden 1976, page 18 f.

[9] Hans H. Hofstätter: Die Bildwelt der symbolistischen Malerei, in: Symbolismus in Europa 1976 (see note 8), page 13

[10] Sven Lövgren: The Genesis of Modernism. Seurat, Gauguin, van Gogh and French Symbolism in the 1880s [Uppsala, Stockholm 1959], New York 1983

[11] Agnieszka Morawińska: Polish Symbolism, in: Symbolism in Polish painting 1890–1914, exhibition catalogue, The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit 1984, page 13–35; republished as: Polski Symbolizm, in: Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, Volume 31, Warsaw 1987, page 467–498, quote page 467, online resource: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/roczmuzwarsz1987/0471/image,info#col_text_ocr