Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

The last-but-one section of the exhibition, entitled “Laughter, Cruelty and Melancholy” (exhibition room text: “Fantastical Worlds”) is dedicated to an exceptional phenomenon in the Polish art of this period: Witold Wojtkiewicz and his scenes showing fairytale figures, clowns, dolls and toys from the theatre, circus and children’s everyday lives.[72] During his short life, which came to an end as a result of a congenital heart disease when he was just 29, he worked mainly in creative cycles consisting of “mysterious stories and somnambulistic-delirious poetry”, producing oil and tempera paintings, watercolours, lithographs and pen and ink drawings. Contemporaries described him as a “great poet, who was able to express himself with perfect painterly means” (Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński) and closely compared his ballad-like, fairytale images with Toulouse-Lautrec, Rops and Beardsley (Antoni Potocki).[73] After studying in Warsaw and Kraków under artists such as Pankiewicz and Wyczółkowski, he moved among Kraków’s bohemian circles and in literary-artistic cabarets, and worked as an illustrator for various magazines.

Wojtkiewicz was not interested in the prevalent Romantic view of Polish history and the myths with which it was associated, but was instead critical of social norms and moral ideals. According to Agnieszka Rosales Rodríguez in her catalogue essay, his imaginary world “is criss-crossed by processions of sad clowns and Pierrots, dolls and marionettes, tragicomic figures who unmask the spectacle-like appearance of life, the emptiness, the apathy and the drama of human existence.”[74] The loneliness in the dance of life, which is permeated with melancholy and compassion, but also with hypocrisy, cold calculation and the premonition of death – here, Edvard Munch comes to mind – was one of his main themes (Fig. 33

Rather abruptly, the exhibition turns in the tenth and final section, “Happy End?” (exhibition room text: “Polonia”) to the political dimension of Polish painting and thus back to the beginning of the exhibition. This clearly rhetorical question refers to the question portrayed by the artists as to whether the end of foreign rule in Poland would bring about a happy end. In the historical paintings of Grottger and Matejko, “Polonia” – a symbol of the Polish nation in a similar way to “Marianne” for France or “Germania” for Germany – is shown bound and shrouded in mourning robes. Following the January uprising of 1863/64 in particular, she became a standard motif. As Godetzky explains in his catalogue essay, during the decades that followed, this symbolic figure was subject to re-interpretation.[77] While for Malczewski, the visionary “Polonia” stood as an “Inspiration” (1897, Fig. 36 ), providing orientation for his own creative work, in “Polish Hamlet” (1903, Fig. 37 left), he depicts the painter Aleksander Wielopolski, grandson of a politician who sought to reach a settlement with the Russian occupying power, counting off the petals of a daisy so that he can make a choice between the old, decrepit, chained “Polonia” and the young version of the figure whose chains have been blown away.

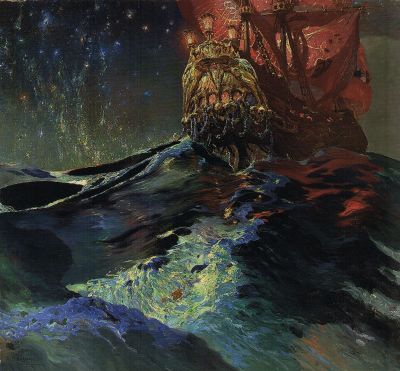

Other pictorial subjects have also been interpreted as allegories for the Polish nation. Witold Pruszkowski shows a female figure bearing a crown as a “Vision” (1890) before a procession of the Polish estates. She appears to be not so much a “Polonia”[78] as the mother of God as protector of the Polish nation, as she is also portrayed in the poem that inspired the painting, “Przedświt” by Zygmunt Krasiński.[79] The mysterious ship depicted by Ruszczyc in “Nec mergitur” (1904/04, Fig. 38 ) has its origins in a literary work, the “Seaman's Legend” by Henryk Sienkiewicz. However, in line with the patriotic spirit, it was interpreted as an allegory of the Polish nation in turbulent waters.[80] The national romantic interpretation of a “Knight Surrounded by Flowers” by Wyczółkowski (1904, Fig. 39 ), who while riding through a field of tulips in 17th century Polish finery is also reminiscent of the Jugendstil fairy tale motifs from other European countries, appears uncertain as well.[81]

[72] Agnieszka Rosales Rodríguez: Gelächter, Grauen und Melancholie. Das malerische Theater des Witold Wojtkiewicz, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 231–239

[73] Ibid., page 231 f.

[74] Ibid., page 236

[75] Ibid., page 237

[76] Leon Wyczółkowski: Ploughing in Ukraine, 1892, National Museum of Kraków, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/136944; Józef Chełmoński: Ploughing, 1896, National Museum of Poznań, https://fundacjaraczynskich.pl/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/FR-17.jpg

[77] Albert Godetzky: Glückliches Ende? Das sich stetig wandelnde Bild der “Polonia”, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 265

[78] Ibid.

[79] See also Leszek Lubicki: Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu. 10 dzieł, które warto znać, at: Fundacja Promocji Sztuki “Niezła Sztuka”, https://niezlasztuka.net/o-sztuce/muzeum-narodowe-w-poznaniu-10-dziel-ktore-warto-znac/

[80] “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 271

[81] See also Heinrich Vogeler: Edge of the Heath, 1900. Oil on canvas, private collection, Berlin (on loan to the Barkenhoff, Heinrich-Vogeler-Museum, Worpswede); Carl Otto Czeschka, illustrations for: Die Nibelungen, Gerlachs Jugendbücherei, Vol. 22, Vienna, Leipzig 1908/09