Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

Visitors to “Polish Symbolism around 1900” may come with firm ideas, formed over the decades, about the pictorial world of “Symbolism in Europe”, to take the title of the early, important exhibition on this topic in 1975–1976 in Baden-Baden, Rotterdam (“Het symbolisme en Europa”), Brussels and Paris (“Le symbolisme en Europe”). If so, they will have to revise their view. As demonstrated by the paintings on show, the Polish version of this style covers a broad timespan from 1875 to 1918 and in some cases presents themes and a style of painting that would not be classified as “Symbolism” in Germany, France or Britain. At first, the strong presence of the historical painter Jan Matejko at the start of the exhibition is a surprise; only recently, in 2018–2019, were we introduced to him as one of the European “Malerfürsten” (“painter princes”) in the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, to a certain extent with the same paintings.[1] However in Munich, together with Wojciech Gerson, he represents the forerunners among the “Polish Symbolist” painters, who opposed historical painting and the political tendencies with which this style was associated.

In an exhibition on “European” Symbolism, therefore, one would be hard put to find some of the paintings shown in Munich: “A Japanese Woman” (1908, Fig. 10 . ) by Józef Pankiewicz, or the night-time view of the “Ludwig Bridge in Munich” (1896/97, Fig. 8 . ) by Aleksander Gierymski, or the Ukrainian woman lying in an open field, in the style of Franz von Lenbach, portrayed in “Indian Summer” (1875) by Józef Chełmoński (Fig. 7 . ), “Cloud” (1902, Fig. 13 . ) by Ferdynand Ruszczyc, which was influenced by Prince Eugene’s Swedish landscapes, the “Boy in School Uniform” (around 1890) by Olga Boznańska, which is reminiscent of Édouard Manet, or the folkloristic figure scenes (1891–1895) by Włodzimierz Tetmajer and Teodor Axentowicz (Figs. 21 . , 22 . ), to name just a few. The prefaces and introductory texts in the catalogue already indicate that the exhibition has something new to offer when they describe the “movement of the so-called ‘Young Poles’”[2] or the “first such comprehensive exhibition of painting by the Young Poles in Germany”[3], while at the same time making hardly any mention of Symbolism, if at all. We are not told whether “Polish Symbolism” and the art of the “Young Poles” are congruent, or whether one is part of the other. Indeed, no mention is made of either in the introductory text in the exhibition hall itself. As a result, a reference to older literature is required in the search for reliable definitions.

From a German perspective, Jost Hermand already described Symbolism in 1959 (and later in 1972) as a “late Romantic current, enriched with certain Impressionist elements” in painting immediately at the turn of the 20th century, in which “spiritistic-occultist elements” predominated with a “conscious antagonism towards positivist materialism”. Inspired by spiritualist secret societies and a tendency towards the “uncanny and inexplicable”, a “mysterious Symbolism” arose, whose adherents in Germany, influenced by the French artists Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Odilon Redon, Eugène Carrière and Gustave Moreau, the Belgian James Ensor and the early works of the Norwegian Edvard Munch, included above all Arnold Böcklin with his allegorical mythical creatures, the Munich artist Franz von Stuck and Max Klinger in his late works, Fernand Khnopff in Belgium and Giovanni Segantini in Italy. Their work was published from 1895 onwards in the Berlin art and literary magazine “Pan”.[4] Similarly, in 1965 (and in the second edition published in 1973), Hans H. Hofstätter described Symbolism as “art that is emphatic and aggressive anti-bourgeois, and sometimes even anti-ethical” with repeated attempts “to break through the positive realism of the bourgeois worldview and world order”.[5] He used the words “pessimism” and “perversion” to describe Symbolism’s aesthetic and used the words “cosmic Symbolism”, “death and eros”, “dream experience”, “the human as mask”, “symbolic forms of woman”, “fetishism” and “satanism” to describe its pictorial worlds.

[1] “Malerfürsten”, exhibition catalogue, Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, catalogue concept: Doris Lehmann and Katharina Chrubasik, Munich: Hirmer 2018; see also the article in this portal, “Malerfürst” Jan Matejko in the Bundeskunsthalle https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/malerfuerst-jan-matejko-der-bundeskunsthalle

[2] Roger Diederen: Preface, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 8

[3] Barbara Schabowska: Greeting, ibid., page 11; similarly Albert Godetzky/Nerina Santorius: Introduction, ibid., page 14

[4] Symbolism chapter in: Richard Hamann/Jost Hermand: Stilkunst um 1900 (Epochen deutscher Kultur von 1870 bis zur Gegenwart, Volume 4 [1959, 1972]), Frankfurt/Main 1977, page 289–304

[5] Hans H. Hofstätter: Symbolismus und die Kunst der Jahrhundertwende. Voraussetzungen, Erscheinungsformen, Bedeutungen [1965], 2nd edition, Cologne 1973, page 9, 23

In 1967, the art historian and professor of aesthetics Renato Barilli, who taught in Bologna, described Symbolism as a cultural movement which began in France during the 1880s and 1890s in the literature of Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud and Mallarmé, while its first manifesto was written by Jean Moréas in the literary supplement to the “Figaro” newspaper in the autumn of 1886. According to Moréas, Symbolism wanted to give the “idea” a form. Charles Morice added that the aim was to achieve a reconciliation between the spirit and the senses, of truth and beauty, faith and joy, science and art, and not least to create “a fruitful alliance between the natural sciences and metaphysics”.[6] In painting, Barilli recognised the “idealists” Puvis de Chavannes and Moreau as being forerunners, traced the beginnings of Symbolism back to Carrière and Redon, and then created a broad arc covering Seurat, Gauguin, Bernard and the Pont-Aven school, van Gogh and the Nabis through to Art Nouveau with Toulouse-Lautrec, Mucha and Grasset.

In his book “Symbolist Art”, published in London in 1972, the art critic Edward Lucie-Smith traced the British Symbolist movement back to the Romantic period, with William Blake and the Pre-Raphaelites Millais, Holman Hunt and Rossetti. However, he also located the true origins of Symbolism in French literature, particularly in Joris-Karl Huysmans, who was inspired by the paintings of Moreau and Redon to explore the themes of decadence and Satanism in his novels “À rebours” (1884) and “Là-bas” (1891). According to Lucie-Smith, Mallarmé, by contrast, derived his understanding of the world from the ambiguous nature of its phenomena and symbols, as well as from astrological and alchemistic ideas, in order to ultimately create a new reality that was at peace with itself.[7]

The “Symbolism in Europe” exhibition showed over 260 works of art from 15 countries, including Poland. The subjects of the works, nearly all of which were figural, were selected based on their depiction of the “imaginative images and forms” according to Moréas’ definition, “in which the ambiguous nature and polymorphism of the idea ... are combined”: “The search for the hidden purpose and the secret meaning in the ‘appearance of the real’ brought the Symbolists to more or less adventurous ‘journeys of exploration’ through space and time, to excavations in the underground caverns of the unconscious [...] The symbolists attempted to discern the spiritual message from the everyday and to show it, not in a natural light, but in the aureole of a revelation.”[8] Hofstätter added that: “The Symbolists also attempted to do what Christianity had undertaken from the beginning: to provide a sense of meaning for our world by imagining a world beyond, and to offer hope for liberation and release from its hardships.”[9] In the exhibition, Polish art was represented by Jacek Malczewski (“Whirlwind”, today: “In the Dust Storm”, 1893–1895, Fig. 18 . ; “Thanatos”, around 1898–1899), many of whose works are shown in the Munich exhibition, as well as by a painting (“The Strange Garden”, 1903) by Józef Mehoffer, whose portrait of his wife sitting in front of Pegasus (1913, Fig. 27 . ) is shown in Munich, and with the tempera painting “Meditations” (1908) by Witold Wojtkiewicz, to whom an entire section is dedicated in Munich.

In Poland, art history research had developed terms to describe art periods that differed from those used in western Europe. Overall, there is a tendency to distil the period around the turn of the 20th century into a single term. In the catalogue published in 1984 to accompany the exhibition “Symbolism in Polish Painting 1890–1914” at the Detroit Institute of Arts (which was reproduced in 1987 in Polish in the Warsaw National Museum’s annual volume), Agnieszka Morawińska argued that the terms “Fin de Siècle” or “Belle Époque” had proven to be too narrow. Finally, it was agreed that the historical term “Young Poland/Młoda Polska” should be used; alternatively, preference was given to the term “Modernizm” used by Sven Lövgren[10], which was rendered into Polish from the original English. According to Morawińska, however, “Modernizm” was also unsuitable, since outside of Poland, the term was increasingly used to describe “the experimental art of the 20th century”[11]. The people responsible for creating the concept for the exhibition in Detroit were certainly aware of the narrower definition of Symbolism coined by Hofstätter based on Moréas’ ideas, as well as of the “Symbolism in Europe” exhibition. Even so, according to Morawińska, when describing the epoch of Polish “thought painting”, or “idea painting/Malarstwo myśli”, which covered a broader spectrum of content, the decision was made to use the word “Symbolism” in relation to the period after Matejko so as not to further exacerbate the terminological chaos.

[6] Renato Barilli: Symbolismus [Milan 1967], Munich 1975, page 8

[7] Edward Lucie-Smith: Symbolist Art, London: Thames and Hudson 1972, page 51–55

[8] Franco Russoli: Bildvorstellungen und Darstellungsformen des Symbolismus, in: Symbolismus in Europa, exhibition catalogue Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden 1976, page 18 f.

[9] Hans H. Hofstätter: Die Bildwelt der symbolistischen Malerei, in: Symbolismus in Europa 1976 (see note 8), page 13

[10] Sven Lövgren: The Genesis of Modernism. Seurat, Gauguin, van Gogh and French Symbolism in the 1880s [Uppsala, Stockholm 1959], New York 1983

[11] Agnieszka Morawińska: Polish Symbolism, in: Symbolism in Polish painting 1890–1914, exhibition catalogue, The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit 1984, page 13–35; republished as: Polski Symbolizm, in: Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, Volume 31, Warsaw 1987, page 467–498, quote page 467, online resource: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/roczmuzwarsz1987/0471/image,info#col_text_ocr

Morawińska continued that it was certainly clear that non-Polish visitors to the exhibition would probably have found it very difficult to understand why certain paintings were defined as being part of the European Symbolism movement.[12] Furthermore, some of the artists represented in the exhibition were only involved with Symbolism for a short period of time. They include Józef Pankiewicz,[13] who is also shown in the Munich exhibition with his purely impressionistic painting “Cart Loaded with Hay” (1890, Fig. 9 . ). The Detroit exhibition also included an image of equestrians (“Insurgent Patrol”, 1873) by Maksymilian Gierymski, a genre scene (“At the Entrance to a Tavern”, 1877) by Józef Chełmoński, the conscious “Cloud” (1902, Fig. 13 . ) by Ferdynand Ruszczyc, or a “Cloud” sketch (1906) by Konrad Krzyżanowski, which was again shown in Munich, since in terms of the history of ideas, these works express the Polish sense of its own history, culture and landscape which is characterised by national romantic sentiment. Naturally, Morawińska was aware of the fact that certain manifestations of Polish landscape painting bore close relation to Scandinavian art. She conjectured that in both artistic regions, there was a deep sense of connection between people and their natural environment and local traditions.[14]

In a similar exhibition at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden in 1997–1998, the decision was made, probably in deference to the German public, to use the main title “Impressionism and Symbolism” to describe the “painting of the turn of the century from Poland”. In her introductory catalogue essay, “Polish painting around 1900”, Elżbieta Charazińska also initially focused on the terminology used. She wrote that various different terms had been used to describe the art of turn-of-the-century Poland, such as Young Poland, Modernism, the modern era, New Art, Symbolism and New Romanticism. Of these, “Young Poland” had remained the most appropriate in relation to “the entire epoch from 1890–1914, with all its artistic manifestations, including literature and music”.[15] In her consideration of Symbolism, the author followed the “Symbolism in Europe” exhibition, which was also shown in the Baden-Baden Kunsthalle in 1975–1976, according to which this term also described the “ideological stance of the artists” in Poland, “which at the end of the century questioned the artistic criteria of Realism and rebelled against scientific objectivity and the standard ways of thinking of that era. [...] Intuitively, they rediscovered the world and humankind, attempted to communicate the ‘unsayable’, the hidden, the secret. They professed their adherence to the pan-psychic principle of the material-spiritual universal oneness of the world.”[16]

According to Charazińska, the first Polish artists to experiment with Impressionism and Symbolism belonged to the circle of artists based in Munich. While Aleksander Gierymski focused his attention on the subject matter of his paintings, on light, colour and the vibrations from light, as well as the twinkling of the streetlamps as the sun set, Witold Pruszkowski was the first Polish artist to acquaint himself with the works of Manet and the Impressionists. The night paintings by Adam Chmielowski, which are characterised by love, loneliness and death, tend towards Symbolism, as do his religious scenes, which are infused with mysticism. Meanwhile, the realist, “genre painter and hymnodist of his native landscape” Chełmoński only began creating atmospheric lyrical landscapes with animals and birds as motifs, as well as “night-time landscape paintings with a strong mystical note” in his late works.[17] By contrast, in her portraits, still lifes, interiors and urban scenes, Boznańska created “her own world, independent of the real-life environment”. Charazińska writes that attempts were occasionally made “to assign Boznańska’s works to the Impressionists; yet her oeuvre is beyond any clear classification. The term ‘Intimism’, which has almost been forgotten today, would perhaps best describe the atmosphere and subject matter of her art”.[18]

[12] Ibid., page 469

[13] Ibid., page 473

[14] Ibid., page 496

[15] Elżbieta Charazińska: Polnische Malerei um 1900, in: Impressionismus und Symbolismus. Malerei der Jahrhundertwende aus Polen, exhibition catalogue Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden 1997, page 11-34, quote page 11

[16] Ibid., page 11

[17] Ibid., page 15

[18] Ibid., page 20

Charazińska names Malczewski, Mehoffer and Wyspiański, who studied under Matejko in Kraków, as being typical representatives of Polish Symbolism, while Tetmajer, also a pupil of Matejko, and Axentowicz with their colourful weddings, processions and harvest festivals in idyllic landscapes demonstrated their solidarity with the Polish country folk, investing them with heroic-mythological features: “The emotive gravity of rural rituals and festivals was seen to reflect the world order, and there was praise for the Polish village landscape as a domain of the blessed, the lost Paradise.” They were followed by the Lviv(/Lemberg/Lwów)-based artists Władysław Jarocki and Kazimierz Sichulski.[19] Ruszczyc and Krzyżanowski “led the beholder ‘into the interior’ of a landscape”, in which emptiness predominated, and in which one could feel “loneliness, a sense of being lost, fear, even horror”. According to Charazińska, they expressed “the existential fears of the people of their age” in a metaphorical way through their landscape paintings.[20] Overall, Charazińska identified four groups of artists: those for whom a significant proportion of their work could be ascribed to Impressionism or Symbolism; those who as “Young Poles” could not be assigned to either of the two groups; and those who added new themes to the canon already explored by Symbolism.

The “Silent Rebels” exhibition in Munich builds on the previous exhibitions in Detroit and Baden-Baden, both in terms of the selection of the artworks shown and the comparative images in the catalogue texts. It also draws on subsequent exhibitions in Raleigh and Chicago in 1993, in Rapperswil in 1996, in Brussels in 2001, in Madrid in 2003, in Dublin in 2007–2008 and finally in Gothenburg in 2018. Conceptually, however, the show aims to go a step further by dividing the works according to their thematic areas, rather than historically or according to the individual artists. In the introduction to the catalogue, however, Albert Godetzky and Nerina Santorius explain that the most important aim of the exhibition is to “familiarise the German public with the subject”, since “Polish art remains relatively unknown among the general population in Germany”.[21]

It therefore comes as a surprise that the subtitle, “Polish Symbolism around 1900”, which is used to describe the temporally and thematically broad epoch from Chełmoński’s “Indian Summer” of 1875 (Fig. 7 . ) or Pruszkowski’s “The Confession of Madej” of 1879, and the paintings of children created in 1918 by Wlastimil Hofman (“Nativity Scene” and “Spring”; Fig. 14 . ), falls short of the differentiated terminology used by Charazińska in the Baden-Baden catalogue. This is particularly striking since it is clearly not at all the case that the “Young Poland” movement “emerged at the beginning of this period”, as is claimed in the introduction; in fact, the term was not coined until 1898, when the literary critic Artur Górski used it in a programmatic article on the literature of that age.[22] There is a further expansion of the conceptual approach taken by the Munich exhibition in that it aims to present “silent rebellions on numerous fronts [...] not just in opposition to political repression, but also as a departure from established artistic traditions”[23]. Whether the overall title, “Silent Rebels”, really is a relevant characterisation of different individuals such as the “painter princes” Jan Matejko and Olga Boznańska, the grande dame of Polish and French painting, remains to be seen.

The first section of the exhibition, with the catalogue text “Obligation and Freedom”, and the less trenchant exhibition room texts, “Serious Fools” (room 1) and “The Art Centres Kraków and Warsaw”[24] (room 2, Fig. 4 . ) initially document the state of Polish painting between 1862 and 1875 with its most important protagonists, Jan Matejko in Kraków and Wojciech Gerson in Warsaw. In the exhibition, these artists are already described as “silent rebels”, whose art was a non-violent protest against the occupying powers of Prussia, Russia and Austria, and who could be regarded as defending and upholding Polish culture.[25] In Kraków, where Matejko had worked as Director of the School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych) since 1873, and from 1875 as the head of the faculty of art at the School for the Higher Women’s Arts (Wyższe kursy dla kobiet), “the policies of the Austrian authorities were less repressive, as a result of which the city had a certain degree of autonomy and better opportunities for developing an artistic infrastructure”, according to Agnieska Bagińska in the catalogue essay on the topic.[26] Against the background of the Polish poesy of the Romantic period, and of the aspirations in art theory during the decades that followed, Matejko understood his historical paintings – in which he dramatically re-created scenes from 16th and 17th century Polish history filled with a large number of human figures and in a monumental format – as being his obligation towards his homeland and its society. He “repeatedly [stressed] the connection between creativity and patriotic feelings”, and regarded himself as a “prophet and teacher of the nation”.[27] He even did so to the extent that in his paintings, he brought together historical figures who had never come into contact with each other in real life, and positioned selected Polish aristocrats in such a way that they could be identified as traitors to the fatherland. In his view, the purpose of historical painting was to interpret the subjects of the works from a present-day perspective, even if this resulted in criticism of the artist by the aristocratic families.

Was the “painter prince” Matejko, who had comfortably settled with his family into his parent’s house, which was located in the old town of Kraków and which had been modernised and ornately refurbished, already a “rebel” merely by way of his art? He and his wife enjoyed a gentrified existence among the upper echelons of society in the city and had their children pose for portraits in aristocratic costume. In 1878, Matejko was presented with a sceptre, which had previously been blessed by the bishop, in the council chamber of the city hall in front of his 4x10-metre historical painting “The Battle of Grunwald”, as “a symbol of his dominance in the sphere of art”[28]. In 1880, he received Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria in his home and presented the monarch with a painting he had completed the previous year, “Meeting of Jagiellonians with Emperor Maximilian at Vienna”. In 1867, Matejko was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph, and in 1887 the Pro litteris et artibus medal of the imperial house of Austria. Thousands of people came to pay their respects at his funeral procession on 1 November 1893. As the Vienna weekly newspaper “Das interessante Blatt” wrote, they bore him to the grave “with true regal honours, since he was a prince of art and in addition a real, true Pole, who bore the ideals of freedom of his people in his soul, who never forgot that he was a son of the land that deems itself the unhappiest on Earth”.[29]

[19] Ibid., page 25

[20] Ibid., page 33 f.

[21] Albert Godetzky/Nerina Santorius: Introduction, in: exhibition catalogue, Stille Rebellen 2022, page 14; list of previous exhibitions in comments 2 to 5 in the same publication

[22] Elżbieta Charazińska 1997 (see note 15), page 27

[23] Godetzky/Santorius (see note 21), page 14

[24] All the exhibition room texts are available as part of the online tour: https://www.kunsthalle-muc.de/en/silent-rebels-digital/.

[25] This is one of the curators of the Munich exhibition, Nerina Santorius, a curator at the Kunsthalle München, in an interview with the online portal culture.pl: “Tytuł wystawy można czytać na kilku poziomach. Cicha rebelia to pozbawiony przemocy protest przeciwko okupantom poprzez sztukę, obrona i kultywowanie polskiej kultury, ale także bunt nowego pokolenia artystów Młodej Polski przeciwko akademickiemu malarstwu historycznemu reprezentowanemu przez Jana Matejkę i Wojciecha Gersona, kwestionowanie patriotycznych zobowiązań artysty połączone z pragnieniem artystycznej wolności.” (Agnieszka Bagińska, Nerina Santorius: Docenić lokalne odcienie symbolizmu [wywiad], https://culture.pl/pl/artykul/agnieszka-baginska-nerina-santorius-docenic-lokalne-odcienie-symbolizmu-wywiad)

[26] Agnieszka Bagińska: Pflicht und Freiheit, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 24

[27] Ibid., page 25

[28] Matejko-Feier, in: Die Presse, Vienna, 31/10/1878, page 10, online resource: https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=apr&datum=18781031&seite=10&zoom=33

[29] Das Leichenbegängniß Jan Matjko’s in Krakau, in: Das interessante Blatt, Vol. XII., No. 47, Vienna, 23/11/1893, page 4 f.; online resource: https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/anno?aid=dib&datum=18931123&seite=4&zoom=33

Wojciech Gerson, who found success in Warsaw after studying in St. Petersburg, Warsaw and Paris, and who from 1872 onwards was a professor at the Warsaw drawing school (Klasa rysunkowa), created historical paintings with similar themes to those of Matejko. Like Matejko, he felt that one purpose of art was to fulfil the artist’s “obligations towards their native country” and to communicate “noble ideas” and give expression to “spiritual beauty”.[30] There are three paintings by Matejko on show at the Munich exhibition: “Blind Veit Stoss with his Granddaughter” (1864, Fig. 4 . 2nd from right), “The Interior of the Tomb of King Kasimir the Great” (1869), and the self-portrait of the artist from the year of his death. All three had been previously included in the Bonn exhibition.[31] The detailed oil on board painting “The Hanging of the Sigismund Bell at the Cathedral Tower in Kraków in 1521”, completed in 1874, is also on display (Fig. 1 . ). “Stańczyk” (1862, Fig. 2 . ) shows a court jester during a ball at the palace of Sigismund the Elder (1507–1548), who (with Matejko’s own facial features) is shown mulling the political situation of Poland and the future of the country. Gerson is also included in the exhibition with a self-portrait, also a scene referencing Veit Stoss (Fig. 4 . right) and with the painting purchased in 2009 from an auction house for the National Museum of Szczecin (Muzeum Narodowe w Szczecinie), “Without Land. Pomeranians, Driven by the Germans to the Baltic Islands” from 1888, which in terms of its composition, motifs and dramatic mood is redolent of “The Raft of the Medusa” (1819) by Théodore Géricault (Fig. 3 . ).

As the Munich exhibition understands it, “Silent Rebels” refers above all to the “new generation of young Polish artists” who turned their backs on academic historical painting, challenged patriotism in art and its obligation towards society, and placed artistic freedom at the forefront of their work. This dissent, and the awakening of a new era, are represented at the start of the exhibition by Leon Wyczółkowski, a pupil of Gerson and Matejko, and Matejko’s pupil Malczewski. Their pictorial themes differ greatly from the historical works of their teachers: Wyczółkowski portrays a desperate “Stańczyk” (1898), who has placed members of traditional Polish society on a wall shelf behind him, lined up as a row of dolls. The works by Malczewski – “Painter’s Inspiration” (1897, Fig. 36 . ), “Vicious Circle” (1895–1897, Fig. 5 . ) and “Painter’s Dream” (around 1888) – depict traditional Polish themes, including the enslaved Polonia, people wearing traditional costumes and prisoners or casualties from former uprisings and wars. They are shown as dreamlike images and ghostly manifestations, and symbolise the rupture experienced by the artist between historical burden and artistic freedom. According to the exhibition room text, Wyczółkowski and Malczewski here represent the “painters of the Young Poland movement”, who established “a new, Symbolist pictorial language”. Here, at the latest, a clear definition of the terms “Symbolism” and “Young Poland” would have been desirable, as well as a differentiation between the two.

In the second section of the exhibition, entitled “Between Paris and St. Petersburg”, Agnieszka Bagińska gives a broad overview of the artists as individuals and the variety of styles of their period (exhibition room text: “In Dialogue with European Art”, Fig. 6 . ). Due to the particular political situation characterised in all three divided areas of Poland by more or less severe suppression of Polish culture, Polish artists – in most cases following initial and very thorough training in Kraków and Warsaw – tended to continue their studies in other European art centres, usually in Paris, Munich, Vienna or St. Petersburg, or even to emigrate abroad. They took with them Polish themes and painting styles and developed these further, formed Polish artists’ groups, befriended local artists, were influenced by them, and continued to exhibit their new work in Poland. Thus, Polish art offers a vibrant facet of European artistic development of outstanding quality. As Bagińska rightly concludes: “It is only with a knowledge of a coexistence of and interconnection between different currents that we can obtain a comprehensive and multifarious picture of European art at the turn of the 19th century”.[32]

[30] Bagińska 2022 (see note 26), page 24 f.

[31] Two of the images in this portal, see note 1

[32] Agnieszka Bagińska: Zwischen Paris und St. Petersburg. Polnische Künstler und die europäische Kunst um 1900, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 57

In Munich, a Polish “school” had already been in existence since 1828, and was particularly strong following the suppression of the Polish uprisings of 1830/31 and 1863/64. Over the course of several decades, it had attracted up to 700 members, who painted in a wide range of different styles and who were naturally influenced by the local artists around them.[33] In 1875, for example, Józef Chełmoński, who was influenced by the Munich Realism style, produced “Indian Summer” (Fig. 7 . ), which was likely based on Lenbach’s “Shepherd Boy” (1860) in the private collection of Count Schack. That same year, he moved to Paris. Adam Chmielowski was inspired by paintings by Arnold Böcklin, also in the Count Schack collection, and created Italian mood landscapes in a similar style. The same collection was also a source of inspiration for Władysław Czachórski’s “Cemetery in Venice” (1876). Witold Pruszkowski was clearly influenced by Symbolism when he created “All Souls” (1888) to mark the Catholic holiday, showing a young girl frightened to death and cowering before an oil lamp in a cemetery. The night-time Munich scenes by Aleksander Gierymski, who lived in the Bavarian capital multiple times and over several years before and after spending interim periods in Paris, where he created impressionistic city vedutas, turned the classical Munich architecture “into a stage for a play of light and shadow”[34] (Fig. 8 . ).

In 1889/90, after training in Warsaw and at the Academy in St. Petersburg, Józef Pankiewicz and Władysław Podkowiński left for Paris. Inspired by Claude Monet, Pankiewicz painted in the divisionist style there (“Cart Loaded with Hay”, 1890, Fig. 9 . ), basing his style on Paul Cézanne with regard to the simplification of form and image space, and increased his autonomy of colour in the manner of his friend Pierre Bonnard and the Nabis group. Podkowiński painted landscapes in shimmering colours and forms that merged into each other (Fig. 6 . centre right). Pankiewicz, who taught at the Kraków Art Academy from 1906 onwards and who passed on his sophisticated colourism to the next generation of pupils, also created works in the Japonesque style (“Japanese Woman”, 1908, Fig. 10 . ), which was also used at times by Boznańska and Leon Wyczółkowski in their interiors, portraits and still lifes. Wyczółkowski, who studied in Warsaw, Munich and Kraków, and who visited Paris multiple times to attend the world exhibitions, transferred the nature experiences of the Barbizon school and the French Impressionists to genre and landscape motifs from Ukraine (“Fisherman”, 1891, Fig. 6 . centre). Kazimierz Stabrowski, Ruszczyc, Krzyżanowski and other artists also studied at the St. Petersburg Academy.

In keeping with the spirit of the exhibition, the third section, “Landscapes of Mourning and Hope” (Fig. 11 . ) should be regarded as the particular Polish route to European Symbolism, which otherwise largely ignores the artistic interpretation of the landscape. As Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha explains, in divided Poland, which was subject to foreign rule, landscape painting “was assigned an important role in society in the fight for the survival of the nation”. Its purpose was to “compensate for the loss of homeland by emphasising the beauty of the Polish landscape”. In around 1900, the unspectacular views of the Romantic and Biedermeier period had given way to “symbolic landscape visions, which were interpreted not only as a metaphor for a lost homeland, but also as artistic reflections on the world, on world order or on human fates”.[35] Individual motifs such as trees whipped by the wind, clouds racing through the sky, gushing bodies of water and flowering or withered meadows served as an expression of psychological states of mind. In the works of Jan Stanisławski (Fig. 12 . ), who was head of the landscape class at the Kraków Academy from 1896–1907, the emptiness of the landscape space and a particular position of the horizon line emphasised feelings of loneliness and fear.

[33] See also the following articles in this portal: “Polish artists in Munich, 1828-1914”https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/polish-artists-munich-1828-1914, “Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890” https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/ateliers-polish-painters-munich-ca-1890, and the list of individual biographies of the “Munich School, 1828–1914“, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/lexikon/muenchner-schule-1828-1914 with the associated biographies in the Encyclopaedia Polonica.

[34] Bagińska 2022 (see note 32), page 51

[35] Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha: Landschaften der Trauer und der Hoffnung. Naturdarstellungen in der Malerei des Jungen Polen, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 77

His successor Ferdynand Ruszczyc saw the fragmentation of mankind embodied in the drama and dynamic of nature. In his paintings, he pursued a “pictorial vision of Earth”[36] and symbolised the uncontrollability of nature. The obvious proximity of his painting “The Cloud” (1902, Fig. 13 . ) to the almost identical subject matter painted in 1896 by the Swedish landscape artist Prince Eugen,[37] whose works expressed national romantic ideas in relation to the Swedish landscape, is evidence of Ruszczyc’ appreciation of Scandinavian painting. Similarly, Wojciech Weiss, who was Rector of the Kraków Academy from 1907, was inspired by Edvard Munch to create landscape images in which expressive light symbolism reflected inner states of the soul. His bleak autumn and winter landscapes, which embodied death and transience, were influenced by literary themes of Stanisław Przybyszewski. For many artists, the Tatra mountains and the spa town of Zakopane at their foot became a place of longing for pure, unadulterated nature and for an original sense of “Polishness”. In paintings such as “Foehn Wind” (1895, Fig. 11 . right) Stanisław Witkiewicz, who moved there in 1890, created images of his vision of a “symbolic meaning of the majestically lying rocks”[38] in the form of a national pictorial epos.

To date, childhood and youth have hardly been acknowledged at all as a separate theme in European Symbolism, although there is sufficient evidence in favour of doing so. While since the early industrial period, children had been brought up as small adults in bourgeois circles, or out of simple necessity were maltreated as work slaves within the poorer levels of society, at the turn of the 20th century, childhood was perceived as being a separate phase in life, with youth as the flourishing of life. Finally, the Lebensreform movement (Fidus: “Light Prayer”, 1913) viewed children as powerful figures of light. This change in attitude is also reflected in numerous Symbolist works. In Hans von Marées work showing “Life Ages” (1873/74), children play a central role. Puvis de Chavannes had crowds of children playing naked and outdoors with sheep in the presence of their mothers (“Summer”, 1873). For Elisabeth Sonrel, they became a symbol of blossoming life (“Procession of Flora”, 1897), and Maurice Denis also rarely passed up on an opportunity to include children in his pictorial scenes (“Holy Women at the Tomb”, 1894). Magnus Enckell depicted a naked boy pondering over a skull as a symbol of human fate (1892). In Max Klinger’s and Edvard Munch’s works, children sit or stand at the bed of their dead mother, or for Walter Crane are mown down by the “Reaper” (1900/09). Jens Willumsen shows a boy running under a blazing sun after his anguished mother, whose husband has died a seaman’s death (“After the Tempest”, 1905). For Segantini, children in a tree symbolise the “Angel of Life” or the “Child Murderer” (both 1894). Young adults at the crossroads between innocence and awakening sensuality are portrayed by Franz von Stuck (“Innocentia”, 1889) and Ferdinand Hodler (“Spring”, 1901). “The Strange Garden” (1903) by the Polish artist Józef Mehoffer, which is displayed and acknowledged early on in the exhibition has given rise to various different interpretations of the naked boy with raised hollyhock stems: from Puck in a Polish “Midsummer Day’s Dream”[39] to the “notion of a carefree existence far removed from all time and civilisation”, as Godetzky writes in the fourth contribution to the Munich catalogue in an essay entitled “Street Children of the Atelier”.[40]

To the credit of the Munich exhibition, it dedicates an entire section to this topic (exhibition room text: “Spring Awakening”), filling it with works from Polish museums that are rarely shown (Fig. 14 . ). Similarly to the Symbolist works from other European countries which associate childhood and youth with themes such as “innocence, purity, incorruptibility, new beginnings, life force, religious piety, the natural world and, above all, spring”,[41] Wojciech Weiss showed a youthful figure at the threshold between childhood and sexual awakening (“Springtime”, 1898, Fig. 15 . ), while in the background, naked adults chase each other in the open fields. During this same period, Weiss studied the writings of Przybyszewski, in which he discussed sexual awakening and erotic desire as the real impulses for tensions within society.[42] Malczewski portrays himself as a satyr with cloven hoofs, abducting two street urchins (“My Models”, 1897, Fig. 16 . ) into the realm of fantasy, surreal dreams and creativity on the path leading to his atelier. This atelier, according to reports by the contemporary writer and art critic Konstanty Górski, was “a place of libertinism and frivolity”[43]. Malczewski’s pupil Wlastimil Hofman depicted “Spring” (1918, Fig. 14 . left centre) as a childlike faun or satyr, a typical creature from the Symbolist world of Arnold Böcklin,[44] thus portraying childhood as a time of uncontrolled, unpredictable animalist impulses.

[36] Ibid., page 80

[37] Prince Eugen: Cloud/Molnet, 1896, oil on canvas, 119 x 109 cm, Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde, Stockholm, https://collection-pew.zetcom.net/sv/collection/item/82416/

[38] Kozakowska-Zaucha 2022 (see note 35), page 82

[39] Symbolismus in Europa 1976 (see note 8), page 128

[40] Albert Godetzky: Straßenkinder des Ateliers. Jugend und Kindheit als Sujets in der polnischen Malerei um 1900, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 112. Godetzky refers to Agnieszka Morawińska: Hortus deliciarum Józefa Mehoffera, in: Ars auro prior. Studia Ioanni Białostocki sexagenario dicata, published by Juliusz A. Chrościcki, Warsaw 1981, page 713–718

[41] Godetzky 2022 (see note 40), page 111

[42] Ibid., page 110

[43] Ibid., page 115

[44] Arnold Böcklin: Faun Whistling to a Blackbird, 1864/65. Oil on canvas, 48.8 x 49 cm, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover

In the “Hidden Powers” section, the exhibition returns to a particular path taken by Poland and discusses the recourse to “myths” regarding Polish history, according to the exhibition room text, and the conscious mythologisation of Polish culture, historical facts and individual people through painting.[45] In a similar way to the Polish homeland landscape, traditional farming life was a recurring topos for national awareness of a nation that did not have its own state. A childlike satyr playing to a farm girl on the panpipes (“Art on the Farm”, 1896) and a goddess from the realm of the dead in a suit of armour and with a scythe, who closes the eyes of a praying farmer (“Death”, 1902, Fig. 17 . ), both by Malczewski, raise Polish farm life to the sphere of a myth that idealises that which is primeval and of eternal validity. Wojciech Weiss created a visionary image, which was augmented into a dynamic scene, in which “Scarecrows” (1905), also a symbol of primitive farm life, are chasing a barefooted shepherdess.

The feminine allegory of Polonia, the personification of Poland, also became the subject of mythologisation. In the painting by Malczewski, “In the Dust Storm” (1893–1895, Fig. 18 . ), she is shown in an open field, with bound hands, lifted up from the ground in a rapid swirl, leaving her children behind her. The artist also painted numerous works showing mythological scenes and individual figures who were well known from Polish literature of the Romantic period, and whose origins lay in local legends, fairy tales and religious texts. The tragedy “Lilla Weneda” (1839/40) by Juliusz Słowacki, as well as studies by contemporary historians, who identified the Celts as being one of the original ethnic groups in Poland, inspired him to create a portrait of the Wenendan king “Derwid” (1902, Fig. 19 . ), who was blinded by his enemies and who listens to the sounds of the magical harp that has been taken away from him. This mythology was also a subject of interest for Wyczółkowski, who painted a “Petrified Druid” (1894), who was thought to be situated in another mythological place, on a mountain in the Tatras. His painting, “Sarcophagus” (1895), brought the royal relief portraits of Kasimir the Great and Jadwiga of Anjou in Wawel Cathedral so much to life that they appeared to be on the brink of returning. Unlike the historicist painters, who depicted mythological themes through generally static everyday scenes, such subjects were now furnished with so many contextual, emotional and creative levels that they were able to generate a new wave of enthusiasm for folkloristic and nationalist sentiment.

Even aside from all forms of mythologisation, rural people, their colourful traditions and their deep religious beliefs were regarded as the main pillars of Polish national consciousness. For the leading philosopher and literary critic Stanisław Brzozowski, Catholicism served to provide a sense of order, both for the individual and for the life of the cultural community. Religion was a “supernatural, superhuman fact [...] a living thing”, as is reflected in the title of the sixth section of the exhibition (room text: “Tradition and Religion”).[46] For numerous artists, both Catholic and Jewish, the “religiousness of the people was an example of the living force of tradition”.[47] Their preferred pictorial subjects included scenes from places of worship (Wyczółkowski: “Christ on the Mount of Olives”, 1896), people praying and rapt in devotion (Aleksander Grodzicki: “The Praying Jew”, 1893), as well as Aleksander Gierymski’s silent scene showing two grief-stricken parents sitting in front of their peasant hut next to the lid of a child’s coffin decorated with a cross (“Peasant Coffin”, 1894, Fig. 20 . ). As well as being a pupil of Malczewski, Hofman also studied at the Ècole des beaux-arts in Paris at the turn of the century under the late classicist and orientalist Jean-Léon Gérôme, who by then was already a very old man. Hofman aimed to do nothing less than generate a renewal of religious art; one painting shows a kneeling peasant confessing in an open field before a weather-worn figure of Christ (“Confession”, 1906).[48]

[45] Nerina Santorius: Verborgene Kräfte. Mythen und Mythisierung in der polnischen Malerei um 1900, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 129–137

[46] Agnieszka Skalska: “Ein lebendig Ding”. Zur Tradition und Religion in der Malerei des Jungen Polen, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 153–161

[47] Ibid., page 153

[48] Image on the digital collection portal of the Warsaw National Museum, MN Cyfrowe, https://cyfrowe.mnw.art.pl/pl/katalog/508015

“For the Modernists, the peasantry epitomised the power of survival of the nation at a time when it was not free. With the help of the peasantry as the embodiment of the original Slavic culture, from whom the artists were to draw inspiration, efforts were made to initiate a regeneration in art.”[49] There were contemporary demands for a new, folkloristic sense of colour and line, which was intended to be adopted not only in painting, but also in decorative elements in architecture, the applied arts and fashion. For the critic Artur Górski, this development was reflected in the work of the painter Włodzimierz Tetmajer, and it corresponded to very similar folk art movements in Scandinavia and Germany at the time. Tetmajer, like Axentowicz, had studied in Munich, and brought with him an interest in folkloristic themes from Bavaria and the Alpine region. In Poland, these two artists painted colourful wedding processions, scenes from inns and at Catholic holiday celebrations, processions at religious festivals and funerals, people dancing and playing musicians from Bornowice near Kraków (Fig. 21 . ), where Tetmajer settled down, married a peasant’s daughter and established his own artists’ colony. In the same way, the local population from the Carpathian highlands, the Hutsuls (Fig. 22 . ) and the people of the Podhale region “were elevated to become symbols of folkloristic vitalism in the new Polish art”.[50] Kazimierz Sichulski and Władysław Jarocki, both pupils of Mehoffer and Wyspiański, spent several months in Tatariw in the Polish Carpathian Mountains, were fascinated by the folk costumes and customs of the local population and painted monumental individual portraits as well as the traditional weddings of the region (Fig. 23 . left-hand wall).

While no mention was made at all of Symbolism in the previous essay on religion and tradition, in the seventh section of the exhibition, “Tête-à-Tête with the Portrait” (exhibition room text: “Portraits”), Michał Haake is at pains to point out Symbolist tendencies in Polish portraiture at the turn of the century.[51] This is all the more remarkable in that the Munich exhibition is able to offer important Polish examples of work to substantiate this idea (Fig. 24 . ), while the earlier studies by Hofstätter, Lucie-Smith and the “Symbolism in Europe” exhibition only explored the issue at the margins, rather than in separate sections. Since Symbolism, in Haake’s view, emerged to a particular degree as being the ability of the artists to forge new paths into extrasensory, metaphysical, secretive and spiritual depths “which can neither be comprehended by the cognitive mind, nor described in words”,[52] it appears logical that these tendencies should also be present in the portraits of the period.

The superior-distanced “Self-Portrait in Spanish Costume” (1911, Fig. 24 . left) by Edward Okuń may only be of an anecdotal nature, since the artist had previously seen an exhibition by the Spanish painter Ignacio Zuloaga. In the self-portrait painted in 1896, (Fig. 24 . centre left) by Julian Fałat, who had been Director of the Kraków Art Academy since the previous year and who had introduced fundamental reforms there, the profound, pensive facial expression of the painter, who is interrupted while working, contrasts with dynamic elements such as the moving palette, a blue-and-white track in the snow running diagonally over the canvas, and the dogs running in the upper edge of the painting, depicting different levels of the psyche. In the works of Malczewski, the protagonist of Polish Symbolism, the painter and other portrait subjects are accompanied by the “fantastical creatures from mythology and Romantic poetry” typical of his work.[53] The self-portrait “On One String” (1908, Fig. 25 . ) shows the famous goddess of death in a suit of armour, while the portrait of the poet Adam Asnyik (1899, Fig. 24 . right centre) shows a group of satyrs playing the flute. “Self-Portrait with Death” (1902, Fig. 24 . right) shows a female figure holding a garlanded skull.

In 1900, Weiss painted a “Self-Portrait with Masks” (Fig. 26 . ; reminiscent of “Self-Portrait with Masks” by the Belgian Symbolist James Ensor painted one year earlier[54]). In a letter to his parents, he described the painting as follows: “Paris is seething inside me. Thousands of different races, passions, types. Hence the masks in my arm – a masquerade of feelings. In the foreground, the mask of a woman, a diabolical woman who kills purely for pleasure.”[55] Entirely under the overly powerful influence of a religiosity that may already be in the process of disintegrating, Wyczółkowski shows the important and controversial art critic and collector “Feliks Jasieński at the Organ” (or rather, at the harmonium, 1902) as a noticeably small figure below a lamentation of Christ that has almost disappeared from view and a fragmented sculpture of the crucified Christ from Jasieński’s own collection.[56] Against the background of a Pegasus, mythological symbol of poesy, whose hoofbeat created Hippocrene, the spring that inspired singing and poetry, Mehoffer painted one of many portraits of his wife Jadwiga (Fig. 27 . ), born Radzim-Janakowska and herself a painter, whom he had met in Paris and of whom he claimed that she would “never descend from the plinth of inimitability and originality”[57]. Even if it is likely that the background to the painting was a wall frieze that existed in real life, through his composition, Mehoffer confers a realm of the highest intellectual order onto the telling expression and living embodiment of the portrait subject.

[49] Agnieszka Skalska 2022 (see note 46), page 154

[50] Ibid., page 157

[51] Michał Haake: Tête-à-Tête mit dem Porträt. Die Erneuerung der polnischen Bildniskunst an der Wende vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 179–187

[52] Ibid., page 181

[53] Ibid.

[54] James Ensor: Self-Portrait with Masks, 1899. Oil on canvas, 120 x 80 cm, private collection, Antwerp; Symbolism in Europe 1976 (see note 8), page 66 f.

[55] “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 199

[56] Image on the online collection portal of the National Museum of Kraków, MNK Zbiory Cyfrowe, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/142860

[57] Józef Mehoffer: Dziennik [Diary], published and annotated by Jadwiga Puciata-Pawłowska, Kraków 1975, page 422

By contrast, a connection to Symbolism is not always evident with regard to the portraits by Boznańska shown in this room. Like other women’s portraits by her, in which the face and hands alone stand out against the black of their clothes, hats and hairstyles, her portrait of an unknown woman (Fig. 28 . ), painted in 1891 in Munich or Kraków, is influenced by James McNeill Whistler,[58] whom she clearly admired.[59] In 1888, a larger number of Whistler’s works were shown at the Third International Art Exhibition in the Glaspalast in Munich, at which a “study” by Boznańska was also displayed. The woman in the portrait holds a sprig from a rosebush whose bloom is about to fade. It is the only symbol that stands in relation to her, yet its function does not go beyond that of a traditional attribute. Boznańska’s “Boy in School Uniform” (around 1890)[60] drew inspiration not only from Whistler with his rich palette of grey shades, but also from Manet, with figures standing in front of a pure colour space[61], whereby the question arises regardless as to whether the painting is a portrait (of private or public interest) or whether it shows an idealised figure (naturally one that is based on a real-life model). However, paintings can be interpreted differently depending on the period in which they are viewed. In 1896, Boznańska’s “Girl with Chrysanthemums” (1894),[62] which today might appear to us to be without a deeper meaning, led the Swiss art critic William Ritter to make a comparison with the characters created by the Symbolist writer Maurice Maeterlinck: “She is a mysterious child, who drives anyone who looks at her for too long, to distraction. This disconcerting blonde girl, who is so pallid it makes one shudder, evokes a six-year-old Mélisande.”[63] The link to the painting “Innocentia” by Franz von Stuck,[64] in which an adolescent figure carries a white lily as a symbol of innocence, and which caused a furore when it was shown in the Glaspalast in 1889, is obvious.

The eighth section of the exhibition, “The Naked Soul”,[65] could be regarded as a deeper examination of the themes already covered, particularly since this section shows two portraits: the ghostly self-portrait of the painter Gustaw Gwozdecki (1900)[66], who had just been accepted to the Kraków Academy, and the portrait of the Kraków-based painter Antoni Procajłowicz as a “Melancholic (Requiem)” (1898, Fig. 29 . ) by Wojciech Weiss. Through the painting’s title, Weiss creates a link to the short story “Requiem” (1893) by Przybyszewski, which had already served as inspiration for Edvard Munch (“The Scream”, 1893). Weiss, who maintained close contact with the writer, shows the “Melancholic”, who examines his unconscious inner self and who finds release in unbridled sexuality, symbolised by his hands held over his crotch.[67]

Above all, however, this section of the exhibition shows paintings that symbolise delirious-Dyonisian states of the soul, “The intoxication of sexual ecstasy, demonic power, the thrill of sunset and humid summer nights [...] the rapture of ecstatic excitement and Dyonisian frenzy, the longing and the pain”, as Przybyszewski wrote in 1892 in his essay “Chopin and Nietzsche” in the series “On the Psychology of the Individual”. Weiss and Podkowiński in particular followed Przybyszewski’s call for “new art as an expression of states of the soul”[68]: “Art is [...] the replication of the life of the soul in all its forms of expression, be they good or evil, ugly or beautiful”, wrote Przybyszewski in 1899 in his literary manifesto “Confiteor” in the Kraków newspaper “Życie”, which he edited.

In “Obsession” (1899/1900, Fig. 30 . ), Weiss shows a surging wave of human bodies merged into each other, in which a woman holds a head with Przybyszewski’s features in blind ecstasy. “The role of perpetrator and victim”, Santorius writes in her catalogue essay, indicate a “demonisation of female sexuality” as “a commonplace of the era, whose story is reflected by Przybyszewski”.[69] Similarly, in his oil sketch “Frenzy” (1893, Fig. 31 . ), Podkowiński shows a female figure benighted by a sexual urge being driven down a steep mountain slope to certain death by the black stallion with which she is locked in an embrace. In 1894, the painting, which is over three metres high, and which in the words of Wacława Milewska embodied “the ecstasy of sensual intoxication, which borders on the destructive force of frenzy”,[70] caused a major scandal in the Zachęta art society, since it was said to depict the unfulfilled love of the artist. The matter did not end there: one day, the artist himself climbed a ladder at the exhibition and slashed the painting with a knife. Later, he claimed that the ripping sound of the canvas sounded like a scream, and the splintering of the wooden stretcher frame like the bones of a dissected corpse.[71] In his final painting, created before he died aged 28 from tuberculosis, he symbolically buried the woman he loved in an artistic vision entitled “Funeral March” (oil on canvas, 1894, Fig. 32 . ), in which he himself, in a night-time scene, turns in a screaming gesture, with ravens screeching and the sound of death bells ringing, towards a passing group of white angels who bear an open casket containing the female corpse. The title of the painting refers to the poem of the same name by the Romantic Polish poet Kornel Ujejski, which in turn refers to the movement of a piano sonata by Chopin of the same name. Chopin’s music not only influenced poets and writers, as is evidenced by the dedication of Przybyszewski’s “Requiem” to the polonaise in F-sharp minor Op. 44 by the composer, but visual artists as well.

[58] See also James Abbott McNeill Whistler: Arrangement in Black: “The Lady in the Yellow Buskin”, in 1883. Oil on canvas, 248.9 × 141.6 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/104367

[59] See also the article in this portal “Olga Boznańska – Kraków, Munich, Paris“, page 6, https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/olga-boznanska

[60] Image in this portal in the article on Olga Boznańska (see note 59), Fig. 13

[61] See also Édouard Manet: Le fifre, ca. 1866. Oil on canvas, 160.5 x 97 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/le-fifre-709

[62] Ibid., Fig. 23

[63] “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 221

[64] Franz von Stuck: Innocentia, 1889. Oil on canvas, 68 x 61 cm, private collection, Paris, see also Symbolism in Europe (see note 8), page 222 f.

[65] Nerina Santorius: Die “nackte Seele”. Polnische Malerei des Fin de Siècle im Spiegel der Schriften Stanisław Przybyszewskis, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 205–211

[66] Image on the online collection portal of the National Museum of Kraków, MNK Zbiory Cyfrowe, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/97458

[67] Wacława Milewska on the online collection portal of the National Museum of Kraków, MNK Zbiory Cyfrowe, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/296928

[68] Nerina Santorius 2022 (see note 65), page 206

[69] Ibid., page 207

[70] National Museum of Kraków, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/143955

[71] Nerina Santorius 2022 (see note 65), page 205

The last-but-one section of the exhibition, entitled “Laughter, Cruelty and Melancholy” (exhibition room text: “Fantastical Worlds”) is dedicated to an exceptional phenomenon in the Polish art of this period: Witold Wojtkiewicz and his scenes showing fairytale figures, clowns, dolls and toys from the theatre, circus and children’s everyday lives.[72] During his short life, which came to an end as a result of a congenital heart disease when he was just 29, he worked mainly in creative cycles consisting of “mysterious stories and somnambulistic-delirious poetry”, producing oil and tempera paintings, watercolours, lithographs and pen and ink drawings. Contemporaries described him as a “great poet, who was able to express himself with perfect painterly means” (Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński) and closely compared his ballad-like, fairytale images with Toulouse-Lautrec, Rops and Beardsley (Antoni Potocki).[73] After studying in Warsaw and Kraków under artists such as Pankiewicz and Wyczółkowski, he moved among Kraków’s bohemian circles and in literary-artistic cabarets, and worked as an illustrator for various magazines.

Wojtkiewicz was not interested in the prevalent Romantic view of Polish history and the myths with which it was associated, but was instead critical of social norms and moral ideals. According to Agnieszka Rosales Rodríguez in her catalogue essay, his imaginary world “is criss-crossed by processions of sad clowns and Pierrots, dolls and marionettes, tragicomic figures who unmask the spectacle-like appearance of life, the emptiness, the apathy and the drama of human existence.”[74] The loneliness in the dance of life, which is permeated with melancholy and compassion, but also with hypocrisy, cold calculation and the premonition of death – here, Edvard Munch comes to mind – was one of his main themes (Fig. 33 . ). For him, the “imagined circus was not a magical childhood realm of innocence and carefree enjoyment, but a locus horridus, a metaphor for life, in which comedy and tragedy merge into one another”[75] (Fig. 34 . ). In his works, even the portrayal of peasant activities such as ploughing, which artists such as Wyczółkowski and Chełmoński turned into national romantic symbols,[76] became a simplified puppet-like, deformed grotesque, in which a sad clown plods along behind a wooden horse (Fig. 35 . ).

Rather abruptly, the exhibition turns in the tenth and final section, “Happy End?” (exhibition room text: “Polonia”) to the political dimension of Polish painting and thus back to the beginning of the exhibition. This clearly rhetorical question refers to the question portrayed by the artists as to whether the end of foreign rule in Poland would bring about a happy end. In the historical paintings of Grottger and Matejko, “Polonia” – a symbol of the Polish nation in a similar way to “Marianne” for France or “Germania” for Germany – is shown bound and shrouded in mourning robes. Following the January uprising of 1863/64 in particular, she became a standard motif. As Godetzky explains in his catalogue essay, during the decades that followed, this symbolic figure was subject to re-interpretation.[77] While for Malczewski, the visionary “Polonia” stood as an “Inspiration” (1897, Fig. 36 . ), providing orientation for his own creative work, in “Polish Hamlet” (1903, Fig. 37 . left), he depicts the painter Aleksander Wielopolski, grandson of a politician who sought to reach a settlement with the Russian occupying power, counting off the petals of a daisy so that he can make a choice between the old, decrepit, chained “Polonia” and the young version of the figure whose chains have been blown away.

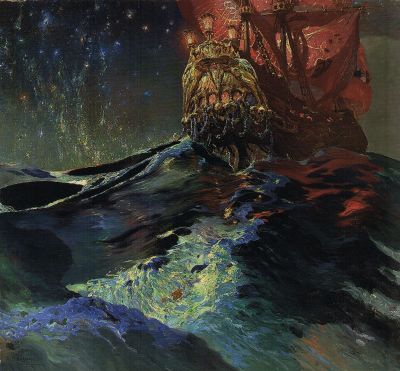

Other pictorial subjects have also been interpreted as allegories for the Polish nation. Witold Pruszkowski shows a female figure bearing a crown as a “Vision” (1890) before a procession of the Polish estates. She appears to be not so much a “Polonia”[78] as the mother of God as protector of the Polish nation, as she is also portrayed in the poem that inspired the painting, “Przedświt” by Zygmunt Krasiński.[79] The mysterious ship depicted by Ruszczyc in “Nec mergitur” (1904/04, Fig. 38 . ) has its origins in a literary work, the “Seaman's Legend” by Henryk Sienkiewicz. However, in line with the patriotic spirit, it was interpreted as an allegory of the Polish nation in turbulent waters.[80] The national romantic interpretation of a “Knight Surrounded by Flowers” by Wyczółkowski (1904, Fig. 39 . ), who while riding through a field of tulips in 17th century Polish finery is also reminiscent of the Jugendstil fairy tale motifs from other European countries, appears uncertain as well.[81]

[72] Agnieszka Rosales Rodríguez: Gelächter, Grauen und Melancholie. Das malerische Theater des Witold Wojtkiewicz, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 231–239

[73] Ibid., page 231 f.

[74] Ibid., page 236

[75] Ibid., page 237

[76] Leon Wyczółkowski: Ploughing in Ukraine, 1892, National Museum of Kraków, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/136944; Józef Chełmoński: Ploughing, 1896, National Museum of Poznań, https://fundacjaraczynskich.pl/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/FR-17.jpg

[77] Albert Godetzky: Glückliches Ende? Das sich stetig wandelnde Bild der “Polonia”, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 265

[78] Ibid.

[79] See also Leszek Lubicki: Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu. 10 dzieł, które warto znać, at: Fundacja Promocji Sztuki “Niezła Sztuka”, https://niezlasztuka.net/o-sztuce/muzeum-narodowe-w-poznaniu-10-dziel-ktore-warto-znac/

[80] “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 271

[81] See also Heinrich Vogeler: Edge of the Heath, 1900. Oil on canvas, private collection, Berlin (on loan to the Barkenhoff, Heinrich-Vogeler-Museum, Worpswede); Carl Otto Czeschka, illustrations for: Die Nibelungen, Gerlachs Jugendbücherei, Vol. 22, Vienna, Leipzig 1908/09

As the end of the First World War approached, and as internal battles were fought for the restoration of the Polish nation, the (apparent) depictions of “Polonia” increased in number. Malczewski shows female allegories of “Slavery”, “War” and “Liberty” in a clear and direct sequence in a triptych (1917, Fig. 37 . right). In “Pythia” (1917, Fig. 40 . ), Godetzky writes that the auguring priestess of the Delphic oracle slips “as it were into the role of Polonia”.[82] In “The War and Us” (1917–1923, title image . ), which he began in Italy and completed in Poland long after the country had gained independence, Okuń shows himself and his wife walking through the final years of the war, accompanied by an old, white-haired woman who personifies hunger, disease and death, with snakes and butterflies in the background as symbols of the enemy threat and joyous hope.

Even after a thorough examination of the exhibition and catalogue, no evidence of “rebels” was found. Furthermore, the over-simplified titles of the individual chapters in the exhibition catalogue tend to misrepresent the core of the problem. The term “Young Poland” also remains a mystery until the end, presumably in the hope that through more frequent use, its meaning will become clearer among the general public and readership. This aside, with its large number of artworks, the exhibition expands and supplements our understanding of European Symbolism in an astonishing way, and places artists centre stage who are largely unknown in Germany. Knowledgeable visitors to the exhibition will encounter numerous “old acquaintances”, whose works have been shown elsewhere in Europe in recent years.[83] Nearly all the works can be viewed online in the digital collections of the Polish national museums or websites in the public domain.

Axel Feuß, July 2022

Exhibition catalogue: Stille Rebellen. Polnischer Symbolismus um 1900, edited by Roger Diederen, Albert Godetzky and Nerina Santorius. With contributions by Agnieszka Bagińska, Albert Godetzky, Michał Haake, Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha, Agnieszka Rosales Rodríguez, Nerina Santorius and Agnieszka Skalska, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthalle München, Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2022, 300 pages.

All links in the notes were last accessed in July 2022.

[82] Godetzky 2022 (see note 77), page 266

[83] See, for example, the exhibition Pologne 1840–1918. Peindre l’âme d’une nation in the Musée Louvre-Lens in Lens, 25/9/2019–25/1/2020, https://www.louvrelens.fr/exhibition/pologne/?tab=exposition#onglet, image selection at france3 hautes-de-france, https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/hauts-de-france/louvre-lens-10-tableaux-decouvrir-nouvelle-expo-pologne-peindre-ame-nation-1727395.html, educational concept: https://education.louvrelens.fr/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/09/Dossier-pedagogique-Pologne_optimise.pdf