Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

In Munich, a Polish “school” had already been in existence since 1828, and was particularly strong following the suppression of the Polish uprisings of 1830/31 and 1863/64. Over the course of several decades, it had attracted up to 700 members, who painted in a wide range of different styles and who were naturally influenced by the local artists around them.[33] In 1875, for example, Józef Chełmoński, who was influenced by the Munich Realism style, produced “Indian Summer” (Fig. 7 ), which was likely based on Lenbach’s “Shepherd Boy” (1860) in the private collection of Count Schack. That same year, he moved to Paris. Adam Chmielowski was inspired by paintings by Arnold Böcklin, also in the Count Schack collection, and created Italian mood landscapes in a similar style. The same collection was also a source of inspiration for Władysław Czachórski’s “Cemetery in Venice” (1876). Witold Pruszkowski was clearly influenced by Symbolism when he created “All Souls” (1888) to mark the Catholic holiday, showing a young girl frightened to death and cowering before an oil lamp in a cemetery. The night-time Munich scenes by Aleksander Gierymski, who lived in the Bavarian capital multiple times and over several years before and after spending interim periods in Paris, where he created impressionistic city vedutas, turned the classical Munich architecture “into a stage for a play of light and shadow”[34] (Fig. 8 ).

In 1889/90, after training in Warsaw and at the Academy in St. Petersburg, Józef Pankiewicz and Władysław Podkowiński left for Paris. Inspired by Claude Monet, Pankiewicz painted in the divisionist style there (“Cart Loaded with Hay”, 1890, Fig. 9 ), basing his style on Paul Cézanne with regard to the simplification of form and image space, and increased his autonomy of colour in the manner of his friend Pierre Bonnard and the Nabis group. Podkowiński painted landscapes in shimmering colours and forms that merged into each other (Fig. 6 centre right). Pankiewicz, who taught at the Kraków Art Academy from 1906 onwards and who passed on his sophisticated colourism to the next generation of pupils, also created works in the Japonesque style (“Japanese Woman”, 1908, Fig. 10 ), which was also used at times by Boznańska and Leon Wyczółkowski in their interiors, portraits and still lifes. Wyczółkowski, who studied in Warsaw, Munich and Kraków, and who visited Paris multiple times to attend the world exhibitions, transferred the nature experiences of the Barbizon school and the French Impressionists to genre and landscape motifs from Ukraine (“Fisherman”, 1891, Fig. 6 centre). Kazimierz Stabrowski, Ruszczyc, Krzyżanowski and other artists also studied at the St. Petersburg Academy.

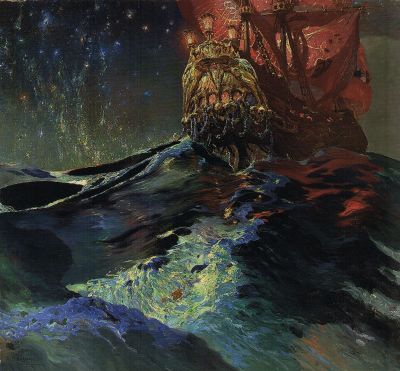

In keeping with the spirit of the exhibition, the third section, “Landscapes of Mourning and Hope” (Fig. 11 ) should be regarded as the particular Polish route to European Symbolism, which otherwise largely ignores the artistic interpretation of the landscape. As Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha explains, in divided Poland, which was subject to foreign rule, landscape painting “was assigned an important role in society in the fight for the survival of the nation”. Its purpose was to “compensate for the loss of homeland by emphasising the beauty of the Polish landscape”. In around 1900, the unspectacular views of the Romantic and Biedermeier period had given way to “symbolic landscape visions, which were interpreted not only as a metaphor for a lost homeland, but also as artistic reflections on the world, on world order or on human fates”.[35] Individual motifs such as trees whipped by the wind, clouds racing through the sky, gushing bodies of water and flowering or withered meadows served as an expression of psychological states of mind. In the works of Jan Stanisławski (Fig. 12 ), who was head of the landscape class at the Kraków Academy from 1896–1907, the emptiness of the landscape space and a particular position of the horizon line emphasised feelings of loneliness and fear.

[33] See also the following articles in this portal: “Polish artists in Munich, 1828-1914”https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/polish-artists-munich-1828-1914, “Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890” https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/ateliers-polish-painters-munich-ca-1890, and the list of individual biographies of the “Munich School, 1828–1914“, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/lexikon/muenchner-schule-1828-1914 with the associated biographies in the Encyclopaedia Polonica.

[34] Bagińska 2022 (see note 32), page 51

[35] Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha: Landschaften der Trauer und der Hoffnung. Naturdarstellungen in der Malerei des Jungen Polen, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 77