Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

By contrast, a connection to Symbolism is not always evident with regard to the portraits by Boznańska shown in this room. Like other women’s portraits by her, in which the face and hands alone stand out against the black of their clothes, hats and hairstyles, her portrait of an unknown woman (Fig. 28 ), painted in 1891 in Munich or Kraków, is influenced by James McNeill Whistler,[58] whom she clearly admired.[59] In 1888, a larger number of Whistler’s works were shown at the Third International Art Exhibition in the Glaspalast in Munich, at which a “study” by Boznańska was also displayed. The woman in the portrait holds a sprig from a rosebush whose bloom is about to fade. It is the only symbol that stands in relation to her, yet its function does not go beyond that of a traditional attribute. Boznańska’s “Boy in School Uniform” (around 1890)[60] drew inspiration not only from Whistler with his rich palette of grey shades, but also from Manet, with figures standing in front of a pure colour space[61], whereby the question arises regardless as to whether the painting is a portrait (of private or public interest) or whether it shows an idealised figure (naturally one that is based on a real-life model). However, paintings can be interpreted differently depending on the period in which they are viewed. In 1896, Boznańska’s “Girl with Chrysanthemums” (1894),[62] which today might appear to us to be without a deeper meaning, led the Swiss art critic William Ritter to make a comparison with the characters created by the Symbolist writer Maurice Maeterlinck: “She is a mysterious child, who drives anyone who looks at her for too long, to distraction. This disconcerting blonde girl, who is so pallid it makes one shudder, evokes a six-year-old Mélisande.”[63] The link to the painting “Innocentia” by Franz von Stuck,[64] in which an adolescent figure carries a white lily as a symbol of innocence, and which caused a furore when it was shown in the Glaspalast in 1889, is obvious.

The eighth section of the exhibition, “The Naked Soul”,[65] could be regarded as a deeper examination of the themes already covered, particularly since this section shows two portraits: the ghostly self-portrait of the painter Gustaw Gwozdecki (1900)[66], who had just been accepted to the Kraków Academy, and the portrait of the Kraków-based painter Antoni Procajłowicz as a “Melancholic (Requiem)” (1898, Fig. 29 ) by Wojciech Weiss. Through the painting’s title, Weiss creates a link to the short story “Requiem” (1893) by Przybyszewski, which had already served as inspiration for Edvard Munch (“The Scream”, 1893). Weiss, who maintained close contact with the writer, shows the “Melancholic”, who examines his unconscious inner self and who finds release in unbridled sexuality, symbolised by his hands held over his crotch.[67]

Above all, however, this section of the exhibition shows paintings that symbolise delirious-Dyonisian states of the soul, “The intoxication of sexual ecstasy, demonic power, the thrill of sunset and humid summer nights [...] the rapture of ecstatic excitement and Dyonisian frenzy, the longing and the pain”, as Przybyszewski wrote in 1892 in his essay “Chopin and Nietzsche” in the series “On the Psychology of the Individual”. Weiss and Podkowiński in particular followed Przybyszewski’s call for “new art as an expression of states of the soul”[68]: “Art is [...] the replication of the life of the soul in all its forms of expression, be they good or evil, ugly or beautiful”, wrote Przybyszewski in 1899 in his literary manifesto “Confiteor” in the Kraków newspaper “Życie”, which he edited.

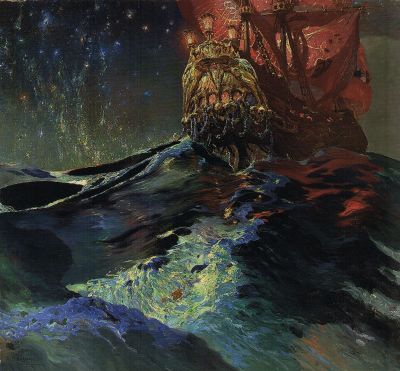

In “Obsession” (1899/1900, Fig. 30 ), Weiss shows a surging wave of human bodies merged into each other, in which a woman holds a head with Przybyszewski’s features in blind ecstasy. “The role of perpetrator and victim”, Santorius writes in her catalogue essay, indicate a “demonisation of female sexuality” as “a commonplace of the era, whose story is reflected by Przybyszewski”.[69] Similarly, in his oil sketch “Frenzy” (1893, Fig. 31 ), Podkowiński shows a female figure benighted by a sexual urge being driven down a steep mountain slope to certain death by the black stallion with which she is locked in an embrace. In 1894, the painting, which is over three metres high, and which in the words of Wacława Milewska embodied “the ecstasy of sensual intoxication, which borders on the destructive force of frenzy”,[70] caused a major scandal in the Zachęta art society, since it was said to depict the unfulfilled love of the artist. The matter did not end there: one day, the artist himself climbed a ladder at the exhibition and slashed the painting with a knife. Later, he claimed that the ripping sound of the canvas sounded like a scream, and the splintering of the wooden stretcher frame like the bones of a dissected corpse.[71] In his final painting, created before he died aged 28 from tuberculosis, he symbolically buried the woman he loved in an artistic vision entitled “Funeral March” (oil on canvas, 1894, Fig. 32 ), in which he himself, in a night-time scene, turns in a screaming gesture, with ravens screeching and the sound of death bells ringing, towards a passing group of white angels who bear an open casket containing the female corpse. The title of the painting refers to the poem of the same name by the Romantic Polish poet Kornel Ujejski, which in turn refers to the movement of a piano sonata by Chopin of the same name. Chopin’s music not only influenced poets and writers, as is evidenced by the dedication of Przybyszewski’s “Requiem” to the polonaise in F-sharp minor Op. 44 by the composer, but visual artists as well.

[58] See also James Abbott McNeill Whistler: Arrangement in Black: “The Lady in the Yellow Buskin”, in 1883. Oil on canvas, 248.9 × 141.6 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/104367

[59] See also the article in this portal “Olga Boznańska – Kraków, Munich, Paris“, page 6, https://www.porta-polonica.de/en/atlas-of-remembrance-places/olga-boznanska

[60] Image in this portal in the article on Olga Boznańska (see note 59), Fig. 13

[61] See also Édouard Manet: Le fifre, ca. 1866. Oil on canvas, 160.5 x 97 cm, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/le-fifre-709

[62] Ibid., Fig. 23

[63] “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 221

[64] Franz von Stuck: Innocentia, 1889. Oil on canvas, 68 x 61 cm, private collection, Paris, see also Symbolism in Europe (see note 8), page 222 f.

[65] Nerina Santorius: Die “nackte Seele”. Polnische Malerei des Fin de Siècle im Spiegel der Schriften Stanisław Przybyszewskis, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 205–211

[66] Image on the online collection portal of the National Museum of Kraków, MNK Zbiory Cyfrowe, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/97458

[67] Wacława Milewska on the online collection portal of the National Museum of Kraków, MNK Zbiory Cyfrowe, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/296928

[68] Nerina Santorius 2022 (see note 65), page 206

[69] Ibid., page 207

[70] National Museum of Kraków, https://zbiory.mnk.pl/pl/wyniki-wyszukiwania/katalog/143955

[71] Nerina Santorius 2022 (see note 65), page 205