Were they really “rebels”? The Munich exhibition “Silent Rebels. Polish Symbolism around 1900”

Mediathek Sorted

In the “Hidden Powers” section, the exhibition returns to a particular path taken by Poland and discusses the recourse to “myths” regarding Polish history, according to the exhibition room text, and the conscious mythologisation of Polish culture, historical facts and individual people through painting.[45] In a similar way to the Polish homeland landscape, traditional farming life was a recurring topos for national awareness of a nation that did not have its own state. A childlike satyr playing to a farm girl on the panpipes (“Art on the Farm”, 1896) and a goddess from the realm of the dead in a suit of armour and with a scythe, who closes the eyes of a praying farmer (“Death”, 1902, Fig. 17

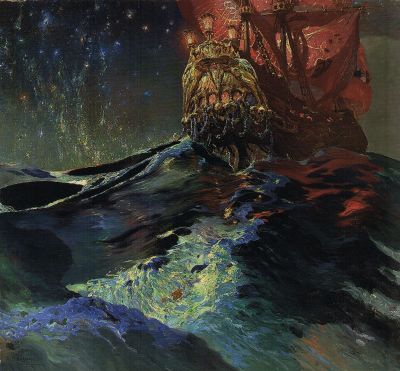

The feminine allegory of Polonia, the personification of Poland, also became the subject of mythologisation. In the painting by Malczewski, “In the Dust Storm” (1893–1895, Fig. 18

Even aside from all forms of mythologisation, rural people, their colourful traditions and their deep religious beliefs were regarded as the main pillars of Polish national consciousness. For the leading philosopher and literary critic Stanisław Brzozowski, Catholicism served to provide a sense of order, both for the individual and for the life of the cultural community. Religion was a “supernatural, superhuman fact [...] a living thing”, as is reflected in the title of the sixth section of the exhibition (room text: “Tradition and Religion”).[46] For numerous artists, both Catholic and Jewish, the “religiousness of the people was an example of the living force of tradition”.[47] Their preferred pictorial subjects included scenes from places of worship (Wyczółkowski: “Christ on the Mount of Olives”, 1896), people praying and rapt in devotion (Aleksander Grodzicki: “The Praying Jew”, 1893), as well as Aleksander Gierymski’s silent scene showing two grief-stricken parents sitting in front of their peasant hut next to the lid of a child’s coffin decorated with a cross (“Peasant Coffin”, 1894, Fig. 20

[45] Nerina Santorius: Verborgene Kräfte. Mythen und Mythisierung in der polnischen Malerei um 1900, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 129–137

[46] Agnieszka Skalska: “Ein lebendig Ding”. Zur Tradition und Religion in der Malerei des Jungen Polen, in: “Stille Rebellen” exhibition catalogue, 2022, page 153–161

[47] Ibid., page 153

[48] Image on the digital collection portal of the Warsaw National Museum, MN Cyfrowe, https://cyfrowe.mnw.art.pl/pl/katalog/508015