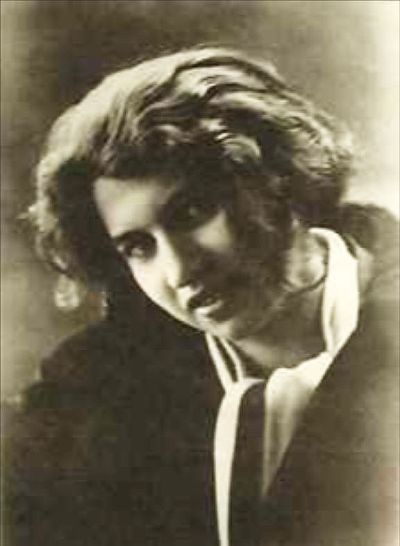

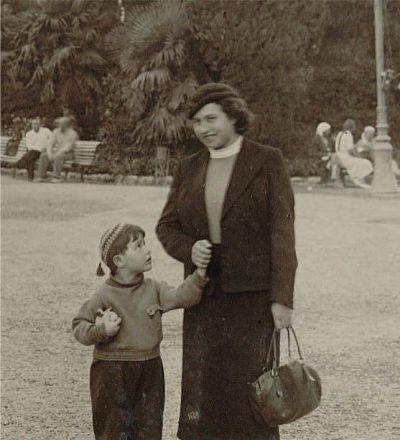

Dora Diamant. Activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Mediathek Sorted

According to Brod, Dora Dymant “came from a very well-regarded Polish Orthodox Jewish family. For all the respect she bore for her father, whom she loved, she could not stand the constraint, the narrowness of the tradition [...] Dora escaped from the little Polish town, and found jobs first in Breslau, then in Berlin, and came to Müritz in the employ of the Home. She was an excellent Hebrew student. Kafka was studying Hebrew with special zeal at that time. [...] One of the first conversations between the two ended in Dora’s reading aloud a chapter from Isaiah in the original Hebrew. Franz recognised her theatrical talent; following his advice and under his direction, she later educated herself in this art”.[16]

Fresh back from his summer holiday in Müritz, Kafka decided to “cut all ties [to Prague], get to Berlin and live with Dora”.[17] For the first six weeks, the couple lived on Miquelstraße in Steglitz. Since their landlady, Frau Hermann, immortalised by Kafka in his story “A Little Woman” (Eine kleine Frau, 1924), constantly created difficulties for the young, unmarried Jewish couple, they moved into two rooms on Grunewaldstraße shortly afterwards. Brod continues: “There I went to see him as often as I came to Berlin – three times it must have been in all. I found an idyll; at last I saw my friend in good spirits; his bodily health had got worse, it is true. [...] Franz spoke about the demons which had, at last, let go of him. ‘I have slipped away from them. This moving to Berlin was magnificent, now they are looking for me and can’t find me, at least for the moment.’ He had finally achieved the ideal of an independent life, a home of his own, he was no longer a son living with his parents, but to a certain extent himself a paterfamilias. [...] In this sense I saw Kafka on the right road, and truly happy with his life-companion in the last year of his life, which, despite his frightful illness, perfected him.”[18]

The external circumstances in which the couple lived were dominated by the rampant inflation during the winter months of 1923. Dora is quoted as saying that when Kafka came home after buying purchases in the centre of Berlin, it was “as if he were coming back from the battlefield”. Both suffered great privations. Brod writes that Kafka insisted on making do with his tiny pension: “Only in the worst case and under great pressure will he accept money and parcels of food from his family. [...] There is a shortage of coal. Butter, he gets from Prague”. Even so, he requested “gift parcels” for acquaintances in need, which contained only what was absolutely necessary for survival: “Now live a few days longer on groats, rice, flour, sugar, tea and coffee, and then die as best you can, we can’t do any more for you”. Between Christmas and New Year, Kafka was plagued by severe attacks of fever. Even so, febrile as he was, he and Dora moved to the district of Zehlendorf: “He lived a retired life. Very seldom visitors came from Berlin: Dr. Rudolf Kayser, Ernst Blass”.[19]

Kafka had plans to move to Palestine and together with Dora, “who was such an excellent cook”, to open a restaurant where he would make himself useful as a waiter. In one of the Berlin apartments, Dora, as she later told Brod, burned several of Kafka’s manuscripts at his request: “He commanded it, and, shaking, she obeyed him. Even many years later, she still had regrets that she had complied. She stressed the fact that even today, when presented with the same situation, she would have bowed to Kafka’s will. […] Other documents belonging to Kafka that remained with Dora were seized by the Gestapo after 1933 and were evidently destroyed”.[20]

On 17 March 1924, Brod accompanied Kafka, who by now was severely ill, to Prague, after Dora and Robert Klopstock had taken him to the railway station in Berlin. Klopstock was a medical student from Hungary who himself had fallen ill with tuberculosis during the First World War, and with whom Kafka had become acquainted at the start of 1921 in the sanatorium in the Slovakian health resort Tratranské Matliare.[21] According to Brod, Dora arrived several days later. After spending time along the way with his parents in Prague and in the Sanatorium Wienerwald in Feichtenbach in Lower Austria, Kafka was moved to a clinic in Vienna with laryngeal tuberculosis. “The only car to be had from the sanatorium to Vienna”, Brod reports, “was an open one. There was rain and wind. The whole journey through, Dora stood up in the car, trying to protect Franz with her body against the bad weather”. Dora and Klopstock, now referring to themselves “playfully as Franz’ ‘little family’”, devoted themselves entirely to his care, and finally succeeded in having him transferred to the friendly, light-filled Sanatorium Hoffmann in Kierling near Klosterneuburg.

During the following weeks, Kafka, who was now almost unable to speak or swallow food, found new courage. “He wanted to marry Dora”, Brod writes, “and had sent her pious father a letter in which he explains that, although he was not a practising Jew in her father’s sense, he was nevertheless a ‘repentant one, seeking to return’ and therefore might perhaps hope to be accepted into the family of such a pious man”. The father set off with the letter to Gerrer Rebbe, the highest authority in the Hasidic community, who read the letter, put it on one side, and said “No”. For Kafka, the father’s letter of response was a “bad omen”.[22] On the last day of his life, Kafka worked on corrections for his last book “A Hunger Artist” (Ein Hungerkünstler, 1924) and provided instructions for changing the order of the stories. At four o’clock on the following morning, Kafka's state became critical. Dora was the first to notice and the only way of providing any kind of relief was by administering morphine. Kafka died on 3 June 1924, with Diamant and Klopstock at his side.

[16] Ibid., page 197.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., page 198.

[19] Ibid., page 201–202.

[20] Brod, 1962, German language edition 247 f. (translated from the German). On 8 March 1933, the documents belonging to Kafka were seized by the Gestapo from the apartment of Lutz and Dora Lask in Pariserstraße 13 in Berlin-Wilmersdorf. They included diary entries, 35 letters addressed to Dora and 20 manuscript notebooks. They were kept in the Gestapo archive, were probably taken to Moscow in 1945 with the stock of documents held by the Gestapo and were returned to the GDR during the 1950s. There, they were stored in the Ministry for State Security, and are lying unidentified in what is likely to be an enormous stock of unseen files in the German Federal Archive (Bundesarchiv); see Hans-Gerd Koch: Franz Kafka. Der unbekannte Aktenberg, in: “Süddeutsche Zeitung” dated 6/12/2019, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/kafka-bundesarchiv-gestapo-akten-1.4711090 (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[21] For a biography of Robert Klopstock see also: Robert Klopstock – Kafkas letzter Freund, at: PragToGo, https://prag-to-go.com/kafka-in-prag/themen/familie-und-freunde/robert-klopstock-kafkas-letzter-freund (last accessed on 04.08.2023). See also Robert Klopstock: Mit Kafka in Matliary, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 153–156.

[22] Brod 1962, English language edition (see Bibliography), page 208.