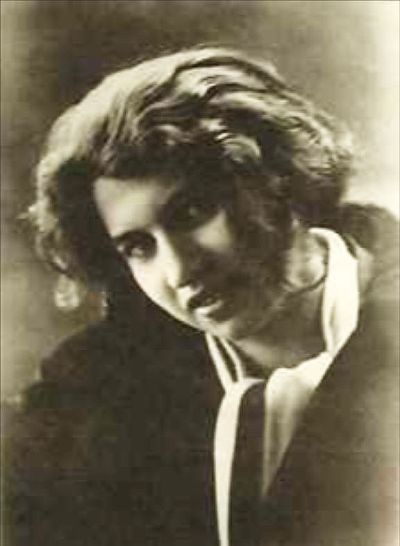

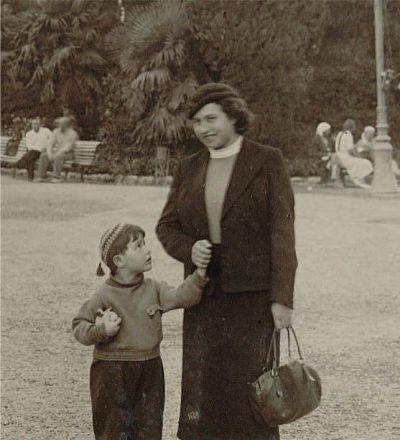

Dora Diamant. Activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Mediathek Sorted

“If only there had been a medicine available” – Kafka’s illness and death

Kafka’s health continued to deteriorate. This was confirmed by his uncle, the country physician Dr. Siegfried Löwy (1867–1942 suicide prior to deportation), who came to Berlin for a few days and who advised him to have himself admitted to a sanatorium. At the beginning of March, Diamant raised the alarm with Dr Nelken from the Jüdisches Krankenhaus. Although he did not find Kafka in bed, the patient was in a terrible state. As Nelken remembered later: “If only Streptomycin or another medication against tuberculosis had been available then. All I could do was to prescribe something to alleviate his cough and other symptoms”.[70] Diamant had abandoned her classes at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies and now dedicated herself fully to caring for Kafka. She earned a small amount of money as a dressmaker. Through his connections, Löwy organised a place for Kafka in a sanatorium in Austria without having to wait. Klopstock travelled to Berlin to offer his support. On 17 March, Kafka travelled to Prague, accompanied by Brod. Diamant remained in Berlin.[71]

Kafka spent three weeks in his parents’ apartment, bedridden and emaciated and weighing just 49 kilograms. He was visited there by Klopstock. There were already signs that the tuberculosis was spreading to his larynx. After Löwy had taken care of Kafka’s admission to the Sanatorium Wienerwald, Diamant travelled to Vienna and visited him on 8 April. “D. is with me, that is very good, she is living in a farmhouse next to the sanatorium”, Kafka wrote to his parents.[72] Just three days later, after being diagnosed with tuberculosis of the larynx, he was moved to Professor Markus Hajek (1861–1941) at the Laryngologische Universitätsklinik in the General Hospital (Allgemeines Krankenhaus) in Vienna, where Kafka was accommodated in a large, multi-bed room filled with dying patients. However, when Felix Weltsch found out about the private lung clinic run by Dr. Hugo Hoffmann in Kierling (Fig. 8

Diamant was also able to live there. She took on the correspondence with Kafka’s parents and sisters, who made telephone calls to the sanatorium every day. At the beginning of May, the Viennese lung specialist, Dr. Oskar Beck, whom Diamant had called on for a consultation, diagnosed a non-treatable condition of the lung and larynx, and advised Diamant to transport Kafka back to his family in Prague. In the interim, Klopstock had also moved into the sanatorium to help care for the patient. The letter from Dora’s father in Poland, whom she had not seen for four years, in which he denied his permission for she and Kafka to marry, arrived on 12 May. On the same date, Brod travelled from Prague to Vienna to visit his ill friend for a day. Brod, Diamant and Klopstock agreed that Kafka should remain in Kierling, since a return to Prague would cause him to lose all hope.[74]

On 25 November 1953, the Prague-born publicist Willy Haas wrote an article about “Franz Kafka’s death” on 3 June 1924 in the Berlin newspaper “Der Tagesspiegel” after a nurse, Anna, who had cared for Kafka until the end in the sanatorium in Kierling, had written him a letter. “Kafka took various precautions in the event of his death. We already know about the agreement with Dr. Klopstock that he should bring about a quick end with a syringe if all hope was lost. It appears that Kafka, in an hour of weakness, granted his life companion Dora permission to die with him. None of these arrangements were followed through. However, the loyal Klopstock did adhere to a third, secret agreement that in the final hour, he was to send Dora away on some pretext so that she would not witness the death struggle. Klopstock did so, and asked Dora to take a letter to the post office. However, in the final minutes, Kafka missed Dora. ‘I sent the maid after her’, the nurse writes, ‘since the post office was close by’. Dora came back out of breath, carrying flowers that she had presumably just bought. Kafka appeared to be fully unconscious. Dora held the flowers in front of his face. ‘Franz, look at the beautiful flowers! Smell them!’, she whispered. ‘Then the dying man sat up and smelled the flowers. [...] He had such wonderfully bright eyes, and his smile said so much, and his hands and eyes were so expressive, now that he could no longer speak’”.[75]

At the request of Kafka’s father, Löwy came to Kierling to take care of the body. According to the nurse’s account, he pushed Diamant and Klopstock to one side “in a rather rough manner” and dealt with the formalities with “cool, indifferent professionalism”. However, an order came via telegram from Kafka’s father on 4 June: “Dora decides”; in other words, she should decide what should happen with the body.[76] Kafka’s body was then taken to Prague by train. Obituaries by Brod, Weltsch, and the writer Oskar Baum (1883–1941) appeared in the German-language Prague newspapers, and Milena Jesenská also wrote an obituary on 6 June in the Czech daily newspaper Národní Listy. On 11 June, Kafka was buried in the New Jewish Cemetery in Prague-Žižkov, with his family and closest friends in attendance. The poet and essayist Johannes Urzidil (1896–1970), who was the press attaché at the German Embassy in Prague, recalled in an essay: “I walked in the wake which followed Kafka’s coffin from the ceremonial hall to the open grave; behind his family and his pale companion, who was supported by Max Brod”.[77] He wrote that Dora broke down at the open grave with anguished, piercing screams.[78]

On the following day, with Diamant present, a memorial ceremony attended by 500 guests was held in the German-language Kleine Bühne theatre in Prague, with speeches and readings from Kafka’s works. During the days and weeks that followed, Diamant remained in Kafka’s parents’ apartment, while Brod began to sort through his literary estate. While doing so, he discovered written instructions from Kafka, addressed to Brod, requesting that “everything written and drawn” that he found in his estate “should be burned completely, without being read”.[79] This would later bring Brod into conflict, not only with his own conscience, but also with Diamant, who later wrote to him that: “Knowledge about Franz should be kept from the whole world. It is none of the world’s concern, because – well, because the world doesn’t understand him.[80]

[70] Gottgetreu 1974 (see note 37).

[71] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 107–122.

[72] Postcard from Franz Kafka to Hermann Kafka, Ortmann 9/4/1924, https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1924/el24-021.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[73] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 123–135.

[74] Ibid., page 137–157.

[75] Willy Haas: Franz Kafkas Tod, in: “Der Tagesspiegel”, Volume 9, No. 2497 dated 15/11/1953, supplement, page 1; reprinted as Willy Haas: Die letzten Tage, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 193–195.

[76] Telegram from Hermann Kafka, archive of the Kafka Research Centre (Kafka-Forschungsstelle) at Wuppertal University (Bergische Universität/Gesamthochschule Wuppertal); quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 161.

[77] Johannes Urzidil: 11 June 1924, in: idem, Da geht Kafka. Essays, Zürich/Stuttgart: Artemis, 1965, page 78.

[78] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 159–166.

[79] Max Brod: postscript to the first edition, in: Franz Kafka. Die Romane. Amerika. Der Prozeß. Das Schloß, Frankfurt/Main: S. Fischer, 1965, page 472.

[80] Dora Diamant to Max Brod, Berlin 2/5/1930, in Max Brod: Der Prager Kreis, Stuttgart et al.: Kohlhammer, 1966, page 113.