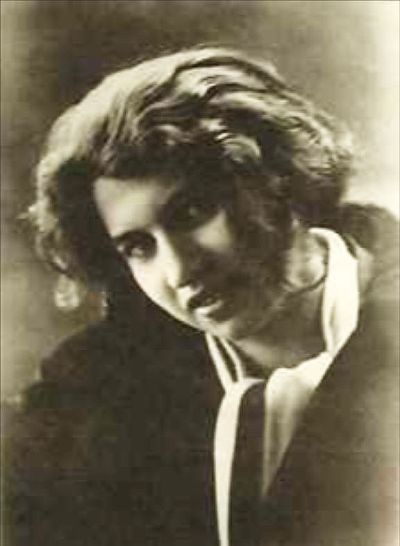

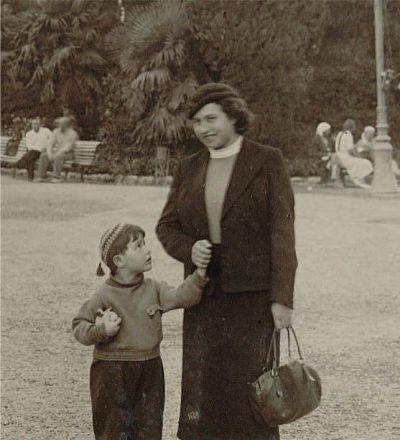

Dora Diamant. Activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Mediathek Sorted

Friends and acquaintances describe Kafka and Diamant

Diamant’s account is supplemented by the reminiscences of Tile Rössler, who was 16 years old at the time, and who had also fallen in love with Kafka in Müritz. In August 1923, she wrote a letter from Müritz to Kafka in Berlin. Her account was recorded by the Austrian writer Martha Hofmann (1896–1975).[9] Tile, born in 1907 as Tehila Ressler in Tarnów in Lesser Poland, in Austrian-ruled Galicia, fled to Berlin with her parents at the outbreak of the First World War. There, she worked as a young trainee in the Jurovicz bookshop in the city, not far from Alexanderplatz. In July 1923, she was also staying at the Jewish holiday home in Müritz. She had already heard of Kafka, having placed a copy of his short story “The Stoker” (Der Heizer, 1913) in the shop window of the bookshop herself. Kafka noticed Tile during a theatre performance given by the children staying in the home and invited her to join him on his wicker beach chair. As she later reported, Tile returned the gesture with an invitation to join them for an evening at the Volksheim. It was there that she introduced Kafka to Dora, who was the kitchen manager there. When Kafka took Tile to a performance of Schiller’s play “The Robbers” (Die Räuber) in the Schauspielhaus theatre after he returned to Berlin, she thought that her hopes for a closer relationship with the famous writer would be fulfilled. Therefore, when Kafka invited her to his apartment in Steglitz, she was all the more disappointed to find Dora there, who was now his partner.[10]

The French essayist, respected Kafka specialist, and Kafka translator Marthe Robert (1914–1996) also remembered Dora Diamant. Three months after Diamant’s death, she published an obituary in the Paris journal “Évidences”, the monthly magazine of the American Jewish Committee. Ten months later, the short text was re-printed in German translation in the monthly culture journal “Merkur. Deutsche Zeitschrift für europäisches Denken”[11]. Robert, who described Diamant as reclusive, with "gloomy" living conditions in London, knew of just one earlier interview, which had been published two years previously by the editor of “Évidences”, the Hungarian-born French journalist and activist Nicolas Baudy (real name Miklos Neumann, 1907–1972). Baudy had interviewed Diamant on topics such as Kafka’s Hebrew lessons and his relationship to Judaism and Zionism.[12] According to Robert, Diamant consistently responded with a clear “No” to repeated questions as to whether Kafka “believed”, in other words, whether he was religious.[13] Robert reported that Diamant had begun to record her memories of Kafka in writing at the start of her own illness. However, Robert’s plan to publish these records never came to fruition.

She quoted word-for-word Diamant’s description of her first meeting with Kafka in Müritz. In particular, however, she made it known for the first time that decades after Kafka’s death, Diamant, who was in exile in London, felt that it was her “calling” to save the Yiddish language from extinction. “In her eyes, Yiddish poetry and literature were the only part of the truth that she could preserve and pass on to others”. She organised lecture evenings, meetings, readings, and theatre performances: “She recited, played, sang, and encouraged others to sing with her – in front of an audience whose connection to old, almost forgotten emotions was reawakened by her. She developed the extraordinary acting skills that she had not wished to develop in the theatre. This passion was engendered within her by the end of Jewish Poland, the Poland from which she, like so many others, had fled in her youth, and yet which she had never really left behind”. According to Robert, she cast her own light onto the world around her. Just as she had radiated it onto Kafka, so “she also spread light onto her environment in the Jewish milieu of Whitechapel, which had become her adoptive home”.[14]

Brod, Kafka’s friend since they had studied together in Prague in 1902, was a supporter, mentor, and collector of Kafka’s literary work, as well as the publisher of his extensive literary estate, including the three major novels “The Castle” (Das Schloss), “The Trial” (Der Prozess), and “America” (Amerika). His biography of Kafka, which was first published in Prague in 1937, and later in 1962 by S. Fischer Verlag in Frankfurt/Main, contains 21 pages of information about Dora Dymant, which has since then been repeatedly re-used elsewhere. In Brod’s view, as he wrote in the chapter “The Final Years”, for Kafka “happiness did come his way [...], and the outcome of his fate was more positive and more full of life than its whole previous development” with his final partner.[15]

[9] Martha Hofmann, a poet, writer, teacher and Jewish activist who was born in Vienna, had probably received the account, together with Kafka’s letter, from Tile Rössler (Tehila Ressler) in around 1940 in Palestine, and subsequently published the novella “Dinah and the Poet” in Hebrew, which centred around Rössler’s meeting with Kafka, in 1942. In 1954, in the Viennese weekly journal “Die Österreichische Furche” (see Bibliography), she revealed that “Dina” was Tile Rössler, again discussed her account, and as an appendix published Kafka’s letter to “My dear Dinah”, or “My dear Tila”, dated Müritz, 3/8/1923 and addressed to the Jurovicz bookshop in Berlin C 2, https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/br23-017.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023). According to Yonat Rotman in 2011 (see below, note 10), the letter is now held in the archive of the Beit Ariela Library in Tel Aviv. In 1995, Hans-Gerd Koch again published Martha Hofmann’s article under the name Tile Rössler, entitled Meeting in Müritz (Begegnung in Müritz), in his collected volume “Als Kafka mir entgegenkam …” (see Bibliography), page 168–173.

[10] From 1925, Tile Rössler/Tehila Ressler trained as a dancer in Mannheim with Irmgard Meyer, a pupil of the choreographer and dance teacher Mary Wigman. She then studied with Wigman herself in Dresden, and also at the dance school founded by Gret Palucca in 1925. Palucca and Rössler had a close relationship. From 1930, Rössler worked as a teacher and school director at the Palucca School. In 1933, she and all other Jewish employees at the school were dismissed as part of the National Socialist “coordination policy” (“Gleichschaltung”). She emigrated to Palestine, where she founded her own dance school, the Tehila Ressler School, in Tel Aviv. In 1943, she established a teacher training programme at her school. The first female pupil was the Israeli dancer, dance teacher, choreographer and textile artist Noa Eshkol (1924–2007). Ressler died in Tel Aviv in 1959. On Tile Rössler/Tehila Ressler, see: Biographisches Lexikon der Theaterkünstler (Frithjof Trapp et al, publisher: Handbuch des deutschsprachigen Exiltheaters 1933–1945, Volume 2), Munich 1998, page 788; Yonat Rotman: Three letters to Tehila Rössler, in: Mahol Akhshav-Dance Today, No. 21, 2011, page 69–71, https://www.israeldance-diaries.co.il/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/DT21_Three_letter_to-Tehila.pdf (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[11] Robert 1952 and Robert 1953 (see Bibliography)

[12] Baudy 1950 (see Bibliography); a copy of the journal can be found in the National Library of France in Paris. See also Iris Bruce: Der Proceß in Yiddish, or The Importance of being Humorous, in: Traduction, terminologie, rédaction (TTR), Volume 7, No. 2, Québec 1994, page 41.

[13] Robert 1953 (see Bibliography), page 239.

[14] Ibid., page 848.

[15] Brod 1962, English language edition (see Bibliography), page 196.