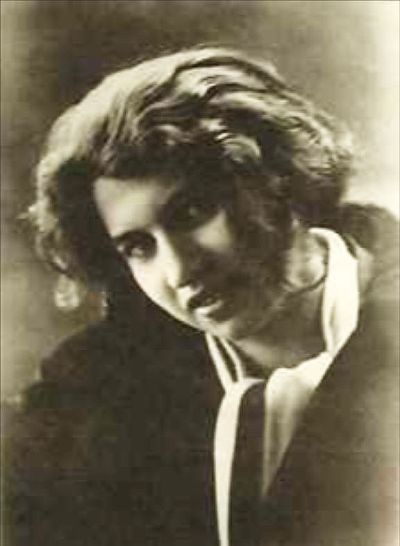

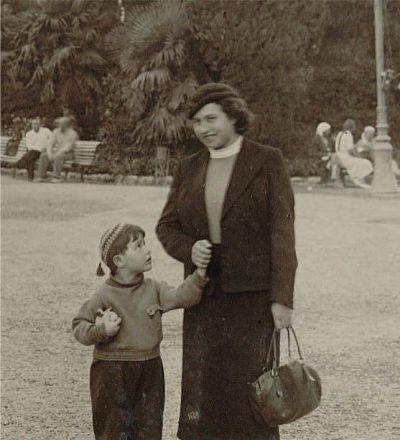

Dora Diamant. Activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Mediathek Sorted

Franz Kafka and Dora Diamant move in together

At last, on 21 September, he seemed to be sufficiently recovered to attempt the journey to Berlin three days later. Even on the way to the station, his father tried to persuade him to change his mind. For his part, Kafka made no mention of Dora’s existence, since his parents had already been incensed by his engagement to Julie Wohryzek (1891–1944, Auschwitz concentration camp), the daughter of a grocer and synagogue sexton. On the two days previously, he had almost backed off from his own “foolhardiness” in moving to Berlin and daring to enter into a new relationship. He had been kept awake during the night by indescribable “fears”. When he arrived in Berlin, the small shared apartment assuaged his fears at first. However, rampant inflation made any kind of normal life almost impossible. In September 1923, a loaf of bread cost 4 million marks. On 2 October, he wrote to Ottla: “... the prices are climbing like the squirrels where you are. Yesterday, they almost made me a bit dizzy, and I find the inner city quite dreadful, for this reason and otherwise. That aside, for the time being, it is peaceful and beautiful here on the outskirts. When I leave the house during these warm evenings, I am met with a scent from the old, lush gardens, which I don’t believe I have ever felt anywhere to this degree of delicateness and intensity...”.[56] Two weeks after his arrival, he told Ottla, Brod and Klopstock that he was considering remaining in Berlin and even spending the winter there.[57] For a long time, he made no mention of “D.”, however, and it was not until 25 October that he wrote to Brod: “The name is Diamant”.[58]

Although Kafka’s pension was paid out in the Czech currency, which was not affected by inflation, his parents only forwarded the money at irregular intervals. Even so, he still hoped that he could make a living as a freelance writer in the future. At first, Diamant had to get used to the hours he spent writing, his silence while he worked and his solitary walks. She enrolled for courses at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies (Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums) (Fig. 6 ) in Artilleriestraße in Berlin-Mitte[59], for which she needed to study at home. She also helped out in the orphanage and continued to work as a volunteer in the Jüdisches Volksheim, where she took up a class in rhythmic dance. During their time together when they were not working, she told Kafka about the life of her family in the Hasidic community in Poland, and they made plans together for a future in Palestine. However, his state of health made it unlikely that they would ever be realised. In mid-November, after the rent on their apartment had risen by more than tenfold in two months when converted into Czech crowns, the couple moved into two “beautifully furnished rooms” with central heating and electric lighting[60] on the first floor of a villa inhabited by Frau Dr. Rethberg at Grunewaldstraße 13 (Fig. 7 ).[61] That same month, Brod came to Berlin with a heavy suitcase full of Kafka’s winter clothes from Prague.[62]

In the interim, Diamant and Kafka had attended several courses at the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies and travelled by tram to the Scheunenviertel district up to three times a week. Diamant studied Jewish laws, the Halacha, while Kafka took lessons in Jewish stories and legends, the Aggada, from the Lwów/Lemberg-born Bible exegete and Semitist Harry Torczyner (Naftali Herz Tur-Sinai, 1886–1973). Ottla brought Kafka’s pension payments from Prague, which could finally be exchanged at the pre-war rate following the introduction of the Rentenmark. For Diamant, Kafka’s sister became a “trusted ally”.[63]

In the winter of 1923, either before or after the short story “A Little Woman” (Eine kleine Frau), which describes and analyses not only the couple’s previous landlady, but also general human behaviour, Kafka wrote “The Burrow” (Der Bau). Only a fragment of the story remains. In the narrative, the protagonist – either a badger or a creature that is a mixture of human and animal – which has just finished digging its underground, labyrinthine abode, becomes paranoid when it hears sounds that steadily increase in volume. The approaching threat, possibly another burrowing animal, causes him to reflect on his own life, at the end of which he is resigned, however, to the nature of his existence and to the impossibility of eliminating the danger. Ultimately, “everything went on unchanged”.[64] Taken in the context of the time at which it was written, the story refers to the “narrowness and heaviness of life in our own, far too expensive, apartment”; the labyrinth is a reference to the Kafka’s deteriorating health and the hopelessness of his situation, together with the threat of returning to his old life in Prague.[65]

Diamant later reported to J.P. Hodin that “The Burrow... was written in a single night. It was winter; he began early in the evening and was finished towards the morning, then he worked on it again. He told me about it, jokingly and in seriousness. It was an autobiographical story, and perhaps it was a premonition of his return to his parents’ house and the end of freedom that generated this sense of panic and fear. He explained to me that I was the ‘citadel plaza’ in this burrow”.[66] In Kafka’s telling of the story, this “central plaza” – possibly Dora – is “well selected for the eventuality of extreme danger, perhaps not of pursuit, but certainly of a siege ... While everything else may be the work more of a concentrated mind than body, this citadel is in all its parts the product of the very hardest manual labour”.[67] Diamant concluded that “He had experienced life as a labyrinth from which he could see no way out”.

It was probably during the Christmas period that Ottla told Kafka’s parents about Dora for the first time. They supported the couple by sending them food parcels. A heavy package arrived from his sisters with household utensils. Before Christmas, Kafka became ill. Every evening during the first two weeks of January, he again suffered from fever, shivering, intestinal problems, and a cough that lasted until the morning. Diamant called a doctor from the Jüdisches Krankenhaus, whose bill, even after she had haggled him down to half the original price, made it clear to Kafka that he could not afford to be admitted to the hospital as an inpatient. The never-ending price increases in the Rentenmark meant that the couple were forced to give notice on their apartment and move out by 1 February 1924. They feared that they would have to leave Berlin entirely. On that date, however, they moved into a one-room apartment in the villa of the widow of the deceased writer and literary critic, Carl Hermann Busse (1872–1918) in Heidestraße 25-26 in Zehlendorf.[68] By this time, Diamant was attending Kafka’s evening appointments, as he himself had been unable to leave the house at night for several months. They included a lecture evening given by the reciter and actor Ludwig Hardt, an acquaintance of Kafka, in the Meistersaal hall on Potsdamer Platz. Diamant rediscovered her own talent for the theatre, and was further encouraged by Kafka and the Prague actress Midia Pines (Midia Kraus, 1893–1965), a friend of Kafka’s.

It was evidently in the Zehlendorf apartment that Diamant burned several of Kafka’s works. She told Hodin that he was obsessed with the idea; to a certain extent, it was a form of stubborn protest: “He wanted to burn everything that he had written in order to free his soul from these ‘ghosts’. I respected his wish, and when he lay ill, I burnt things of his before his eyes. What he really wanted to write was to come afterwards, only after he had gained his ‘liberty’.”[69]

[56] Franz Kafka to Ottla Kafka, Berlin-Steglitz 2/10/1923, in: Franz Kafka: Briefe an Ottla und die Familie, Frankfurt/Main 2011, page 134 f., https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/ok23-106.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[57] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 59-74.

[58] Franz Kafka to Max Brod, arrival postmark Praha-Hrad, 25/10/1923, in: Max Brod, Franz Kafka – eine Freundschaft 1989 (see note 1), page 434 f., https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/bk23-012.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[59] Now Tucholskystraße 9, known as the Leo-Baeck-Haus and headquarters of the Central Council of Jews in Germany (Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland).

[60] Franz Kafka to his parents, Berlin-Steglitz, beginning of November 1923, https://homepage.univie.ac.at/werner.haas/1923/el23-003.htm (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[61] See Karen Noetzel: Vor 90 Jahren genoss Franz Kafka das Vorstadtidyll, in: “Berliner Woche”, 6/1/2014, https://www.berliner-woche.de/steglitz/c-sonstiges/vor-90-jahren-genoss-franz-kafka-das-vorstadtidyll_a43304 (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[62] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 75–92.

[63] Ibid., page 93–105.

[64] Franz Kafka: The Burrow, in: Franz Kafka. The Burrow, London 2017, page 183–220.

[65] Florian Kraiczi: Der Einfluss der Frauen auf Kafkas Werk. Eine Einführung (Schriften aus der Fakultät Geistes- und Kulturwissenschaften, 1), Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press, 2008, page 119–124, https://fis.uni-bamberg.de/bitstream/uniba/118/1/Dokument_1.pdf (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[66] Hodin 1948 (see Bibliography), page 38; quoted from Dora Diamant: Mein Leben 1995 (see Bibliography), page 179.

[67] Kafka: The Burrow (see note 64), page 186.

[68] Today Busseallee 9. The house has been rebuilt and bears a memorial plaque to Franz Kafka. The widow Paula Busse (*1876) was liberated from the Theresienstadt ghetto in 1945.

[69] Hodin 1948 (see Bibliography), page 39.