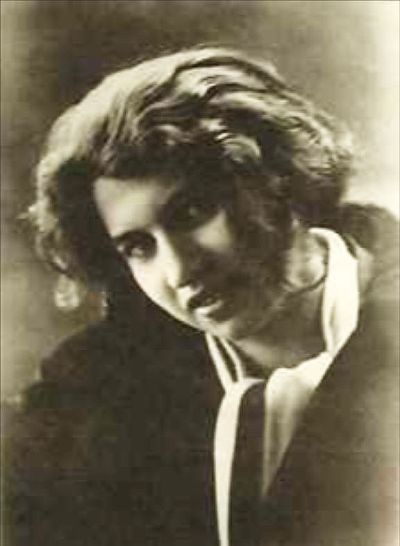

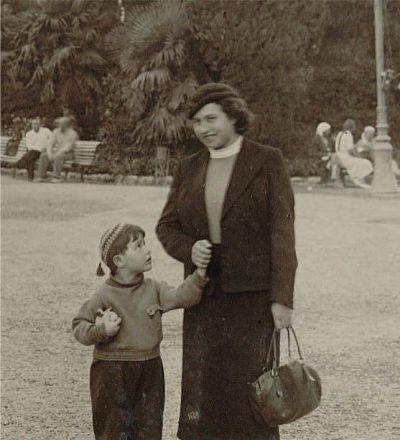

Dora Diamant. Activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Mediathek Sorted

An active member of the Jewish community in London

In August 1941, after having been classified as politically uncontaminated, she was permitted to move to Manchester, to the home of the British philosopher Dorothy Emmet (1904–2000), who at that time was renting a room to a young Kafka researcher. In 1942, she returned to London after taking Marianne to a Quaker-run boarding school to the north of Lancaster. In Whitechapel, in London’s East End, where there was a large Jewish population, she met Stencl again, who before the outbreak of war had already set up a group, the “Friends of Yiddish Group”, which promoted Yiddish literature and culture. The group still exists today. From 1940 onwards, he had been working on a new edition of the journal Loshn un lebn. In Diamant, he found an enthusiastic fellow activist for his “campaign to preserve Yiddish as a living language”[104]. He later reported that Diamant had immediately joined the group and become actively involved in their work after arriving in London: “She organised readings on the afternoons of the Sabbath, read from Jewish literature, particularly from the classics. Dora Dymant’s readings of excerpts from Yiddish stories, or of the poem ‘Monish’, for example, always made the Yiddish literary afternoon a ‘Yontif’, a holy day”.[105] To earn a living for herself, she worked as a dressmaker and opened a restaurant.

After the end of the war, while Marianne lay severely ill in a paediatric hospital in London, Dora tried out her acting skills at the New Yiddish Theatre in the East End. However, in Stencl’s opinion, she was not able to keep up with the standards of the time. Instead, she wrote theatre reviews for Stencl’s journal. In 1947, Marianne was again able to attend the High School in South Hampstead, although she, and by now also Dora, was suffering from severe kidney disease. That same year, Dora invited Josef Paul Hodin to her apartment in London for an interview about Kafka, which lasted for many hours. In 1948, she met Marianne Steiner[106] again in London, the daughter of Kafka’s sister Valli, who had been murdered in the Kulmhof death camp in 1942.[107]

While Dora’s surviving siblings emigrated from Germany to Israel in 1948 and the following year, Dora was forced to remain in London, where her daughter again had to spend two years in hospital. In the interim, she continued to give lectures, readings and performances in Yiddish “during which she dressed in costume and read several parts at the same time – reciting, miming, singing and encouraging others to sing, offering everything to her audience that evoked old, almost forgotten feelings once again”,[108] while the Yiddish culture and way of life gradually disappeared and the Yiddish language coming from Israel went out of fashion in favour of Hebrew.

Diamant remained in close contact with Marianne Steiner and received royalties from Kafka’s estate through her. She exchanged letters with Brod every month. In October 1949, she travelled to Israel for four months. Brod organised a lecture evening with her in the Habima Theater (later the National Theatre) in Tel Aviv, which was attended by an audience from the Mischmar haScharon kibbutz, people from Będzin, and Kafka enthusiasts. Of course, she stayed with her siblings, met Tile Rössler and, in the En Charod kibbutz, saw David Maletz again, her Hebrew teacher from Będzin. In February 1950, she embarked on the return journey to London with the promise to come back to Israel with her daughter Marianne.[109]

On the way back, she visited Paris, where she spent several days as a consultant and reviewer for the actor and director Jean-Louis Barrault (1910–1994) who was producing a stage version of Kafka’s novel The Trial (Der Prozess) at the Théâtre Marigny. She had long conversations with Nicolas Baudy and formed a friendship with Marthe Robert, both of whom published articles about Dora Dymant’s memories of Kafka, either immediately afterwards or at a later date. When Diamant arrived in London, it was clear that her daughter Marianne was too ill to make the journey to Israel. In January 1951, Dora was diagnosed with a rapidly progressing, chronic kidney infection. In March, she began her written notes about Kafka, mostly in German. Confined to bed for weeks on end, she began exchanging long letters with Marthe Robert. Marianne was cared for by the Steiners while her mother lay in hospital.

Diamant witnessed the ever-increasing number of editions and analyses of Kafka’s works that began appearing in the US and Europe from the beginning of the 1950s. In March 1952, the German writer Martin Walser (1927–2023) visited her in her apartment. The previous year, he had completed his doctoral thesis on Kafka,[110] and had collaborated on a joint production between the BBC and the “Süddeutsche Rundfunk” in London. His description of the visit, to mark the publication of Kafka’s “Letters to my Parents” (Briefe an die Eltern)[111] between 1922 and Kafka’s death, reads as follows:

“It was the darkest late afternoon of my life. In the stairwell of the old rented block in Chelsea, there was a kind of night, in comparison with which real night should be called day. I felt my way up the banister. Upstairs, the door was opened by a 13- or 16-year-old girl. She led me to Dora Diamant. All I knew about her was that she had been at Kafka’s side until the end. It has only now become possible to know what exactly happened at that time, thanks to this wonderfully precise letter edition. I say this, because I have rarely bungled an opportunity to such a degree as I did on this afternoon, sitting on the chair next to the bed of the woman who had lived with Kafka for his last two years. I only knew her name from Max Brod’s Kafka biography. There, she is called Dora Dymant, she is 19 or 20 years old, and is introduced in a scene which is, however, unforgettable. [...] Now, around 30 years later, I sat at this woman’s bedside. There was a very small lamp on the nightstand offering a tiny circle of light in the room, which otherwise appeared boundless in the darkness. Dora Diamant’s hair, untied. Perhaps her daughter had just combed it. The daughter who brought me to the chair next to the bed and then disappeared. Dora Diamant looked ill. But for me, the real calamity was not her condition, but my inability to respond appropriately to it. I had hardly sat down before she reached down under one of the many pillows, in front of which she was more sitting than lying. She brought out a kind of school notebook and started to read from it. It was her written notes about Franz Kafka. [...] Through his letters to his parents and Dora Diamant’s additions to these letters, which have now been published, we can intimate that she was one of the few people who awakened an interest in life in Kafka. Yet her notes, which she recorded after Kafka’s death, were not about my Kafka, but about hers. Her Kafka was the founder of a religion, whom I did not know and whom, in my literary narrow-mindedness, I did not want to know. I was incapable of accepting the thoroughly religious lens through which this woman from the eastern Jewish tradition viewed the world as a way of expressing how she experienced Kafka. She spoke of Kafka as though he were a saviour. The light in which someone appears to us always comes from ourselves. [...] Even so, I should have been able to hear the real origin of Dora Diamant’s religious tone. But no: instead, I found the way in which she religiously glorified her Kafka to be rather repugnant. I should have at least remained curious. But no, I was the opposite: narrow-minded. That’s how I botched a unique opportunity with my ridiculous attitude. When I read the sentences written by Dora Diamant in this letters edition, which so precisely preserves her involvement, I realised how close she was to Kafka, what a help she could have been for Kafka. It was then that I again became fully aware of the extent of my failure at the time. I left Dora Diamant sitting in front of her pillows, travelled from Chelsea back to Piccadilly Circus and went to the theatre.”[112]

On 15 August 1952, Dora Diamant died in Plaistow Hospital in West Ham, East London (Fig. 17

Axel Feuß, May 2023

[104] Valencia 1997 (see note 85), page 8.

[105] A. N. Stencl: Über den ersten Jahrestag des Todes der Schauspielerin Dora Dimant, in: Yoyvl-almanakh. Loshn un lebn, 1956. Unzer beyshteyer tsu der fayerung der tsurikker fun yidn for 300 yor in england, London 1956; quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 280.

[106] On Marianne Steiner, the final executor of Kafka’s estate, see Hanns Zischler: Kafkas Nichte. Gedenkblatt für Marianne Steiner, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, No. 264, dated 13/11/2000, page 55; again at https://www.franzkafka.de/fundstuecke/kafkas-nicht-gedenkblatt-fuer-marianne-steiner (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[107] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 272–307.

[108] Robert 1952 (see Bibliography), quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 312.

[109] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 309–322.

[110] First published as Martin Walser: Beschreibung einer Form. Versuch über Franz Kafka (Literatur als Kunst series), Munich: Hanser, 1961.

[111] Franz Kafka: Briefe an die Eltern aus den Jahren 1922–1924, edited by Josef Čermák and Martin Svatoš, Frankfurt/Main: S. Fischer, 1990.

[112] Martin Walser: Kafkas Stil und Sterben. Letzte Briefe und Postkarten, in: Die Zeit, No. 31, dated 26/7/1991, https://www.zeit.de/1991/31/kafkas-stil-und-sterben/komplettansicht (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[113] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 323–363.