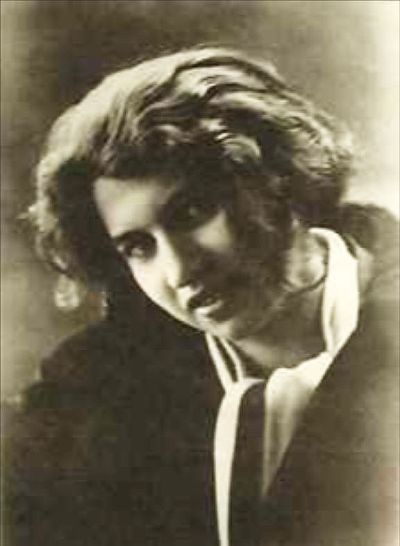

Dora Diamant. Activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Mediathek Sorted

A Jewish life story between Poland and Germany

According to the birth certificate in the registration office in Pabianice, Dworja Diament was born on 4 March 1898, the daughter of Hersz Aron Diament and Frajda Fridl Diament, aged 24 and 25 respectively. In Yiddish, her father’s name was Herszel (Hebrew: Zvi) Aron Lizer Dymant. His wife was known by the Yiddish name Friedel. The earliest records go back to a weaver, Szlama Efroim Dymant, who was born in 1827 in Brzeziny, a few kilometres to the east of Łódź. Twenty years later, he moved to Pabianice with his young family, where weavers and tailors were resettled in order to support the expansion of the cotton industry. Herszel Dymant, who was probably his grandson, and Friedel had a son, David, in 1897. He was followed by Dworja (or Dora), then Jakub, a sister, Nacha, then Abram and another son, Arje. In 1905, the same year as the birth of her youngest son, Dora’s mother died.[30] As the eldest daughter, Dora was assigned the task of taking care of the household and of her siblings.

After the death of his wife, Herszel moved to Będzin with the children. There, the family lived in ulica Modrzejowska, in the area between the castle ruins and the great synagogue (Fig. 1 ), where he ran a successful workshop for suspenders and garters. He was educated, had an extensive library, spoke Polish, German, Yiddish and Hebrew, and was one of the most respected residents in the town. He wore a traditional kaftan, with a beard and sidecurls, was the head of the local Hasidic community under the Rebbe of Ger (Góra Kalwaria) and was responsible for the house of prayer. On the Sabbath, members of the community came to his home, while he dedicated himself to supporting poor families. He did nothing without the approval of the incumbent Gerrer Rebbe, Avraham Mordechai Alter (1866–1948), who in turn referred to “Herszel the Paviancer” – Herszel from Pabianice – as his “diamond”. While at the end of the 19th century, Będzin had the seventh-largest Jewish community in the Kingdom of Poland, with around 11,000 members making up 45 percent of the population of the district mining town,[31] the Gerrer Hasidim dedicated themselves to the study of the Talmud, forbade any kind of reform or modernisation that was not prescribed in the Torah, and opposed the Jewish reformist movements.

Even though in Russian-ruled Congress Poland there was no mandatory schooling for children up to age 14, Dora was permitted to attend Polish schools. For girls, who according to the Jewish laws were not allowed to study the Talmud, a general school education improved their “prospects on the marriage market”. Nevertheless, Dora’s father did not marry her off early, probably because of her duties in the family household.[32] Eager to obtain an education, she joined Hebraica, an organisation founded by Zionist groups in Będzin during the course of the First World War. Based on the first Zionist movement established in 1881, Chibbat Zion, the ideas of Theodor Herzl (1860–1904) and the first Zionist World Congress of 1897, the organisation propagated the founding of a Jewish state and the dissemination of Hebrew as the national language. Although the religious community led by Gerrer Rebbe threatened the parents of the pupils of the organisation, who came from all political and social layers of Jewish society, with exclusion from the congregation, Dora enrolled for courses in Hebrew. The courses offered to girls and women who wanted to teach their children Hebrew were given by the Będzin-born writer David Maletz (1899–1981), one of the later founding members of the Kibbutz En Charod in Palestine, who had studied at a Talmud university (Fig. 2 ).[33] In addition, Dora joined a theatre group, which according to Kathi Diamant’s account was regarded by the “ultraorthodox religious groups” as a “desecration of the Holy Scripture”.[34]

After remarrying in 1918 and fathering more children with his new wife, Herszel Dymant brought Dora to Krakow, where she was to receive training as a kindergarten teacher at the Beis-Ya’acov School (Szkoła Beis Jaakow). This school, which was founded in 1917 by the Polish-Jewish teacher Sara Szenirer (Sarah Schenirer, 1883–1935), and which was followed by other schools that were established worldwide, was supported by Hasidic rabbis such as Gerrer Rebbe, and aimed, for the first time, to provide young Orthodox women with a higher school education while at the same time protecting them against secular influences and assimilation into Polish society. According to Dora’s own account, it was here that she perceived herself for the first time as being a “thinking, aware person”.[35] Nevertheless, she felt so uncomfortable among her fellow pupils that she secretly packed her suitcase and fled to Breslau in Prussia, where acquaintances of hers lived. Her father found out her whereabouts, and brought her first back home, then back to the school in Krakow.

However, Dora ran away a second time, and again travelled to Breslau. This time, her father gave up trying to bring her back. She worked in a children’s home, learned German, and moved in literary and student circles. Her acquaintances included the journalist from Berlin, Dr. Manfred Georg (Manfred George, 1893–1965),[36] who at that time was the chief editor of the “Vossische Zeitung” newspaper in Breslau. Following his expatriation from Germany in 1938, he became editor in chief of the “Aufbau” news-sheet published by the German Jewish Club in New York. The Breslau-born doctor Dr. Ludwig Eleazar Nelken (1898–1985), who studied medicine there at the end of the First World War, and who most recently worked as a doctor in Jerusalem, remembered that Dora, who came from Poland, spoke Yiddish, but learned German very quickly. According to Nelken, the strict devotion of the pretty, intelligent woman to all things Jewish had an influence over a certain number of young Jewish people who had otherwise assimilated or who had joined the left-wing camp (see PDF).[37]

[30] On the early years of Dora Diamant’s life and her family background, see Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 41–50 (German language edition).

[31] See: Będzin, at Świętokrzyski Sztetl – Ośrodek Edukacyjno-Muzealny, http://swietokrzyskisztetl.pl/asp/en_start.asp?typ=14&menu=178&sub=173 (last accessed on 4/8/2023).

[32] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 45.

[33] A description of Hebraica in Będzin by Moshe Rozenkar, one of the founders, is included in the volume by Abraham Samuel Stein (Avraham Shemuʼel Shtain, 1912–1960), which is over 400 pages long, and which is written in Hebrew and Yiddish: Pinkes Bendin. A Memorial to the Jewish Community of Bendin (Poland), Tel-Aviv: Hotsẚat Irgun yotsʾe Bendin be-Yiśrẚel, 1959, page 294, https://archive.org/details/nybc313684/page/n6/mode/2up (last accessed on 04.08.2023). The account also contains the earliest photograph of Dora Dymant, taken in around 1916. She can be seen together with the other women and girls in the Hebrew class and their teacher, David Maletz, page 294.

[34] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 27, 46, 48.

[35] Dora’s own account of her life in the Komintern file in Moscow, quoted from Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 49.

[36] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 49.

[37] Eric Gottgetreu: They knew Kafka, in: “The Jerusalem Post Magazine”, Jerusalem, 14/6/1974, page 16, https://archive.org/details/TheJerusalemPost1974IsraelEnglish/Jun%2014%201974%2C%20The%20Jerusalem%20Post%20Magazine%2C%20%2314%2C%20Israel%20%28en%29/page/n7/mode/2up (last accessed on 4/8/2023). The passages relating to Ludwig Nelken again in German translation as Ludwig Nelken: Ein Arztbesuch bei Kafka, in the collected volume of Hans-Gerd Koch: “Als Kafka mir entgegen kam …” 1995 (see Bibliography), page 186 f.