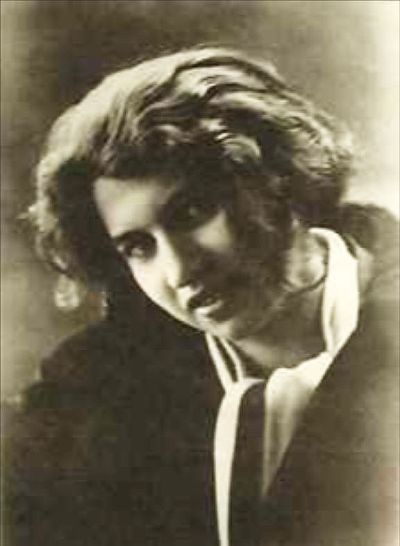

Dora Diamant. Activist, actress, and Franz Kafka’s last companion

Mediathek Sorted

Flight to the Soviet Union and emigration to Britain

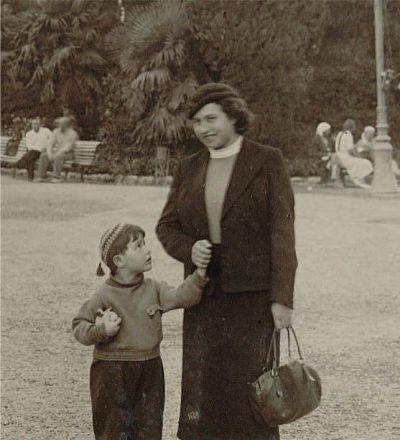

On 1 March 1934, Dora gave birth to a girl, Franziska Marianne. She managed to secure the premature release of her husband from the Gestapo. However, he was required to report to the police station every day. At the end of October, he escaped to his mother in Prague, who a short time later emigrated to Moscow. Lutz followed her to the Soviet Union four months later. While Berta worked as a librarian at the Russian State Library, Lutz was given a job as a research assistant at the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute. In November 1934, Dora applied for permission to leave for the Soviet Union. While she was waiting to receive her papers, she renewed her contact with Stencl and joined his Polish-Jewish group of literati. The Nuremberg Laws, which were passed on 15 September 1935, cemented the exclusion of the Jews from the National Socialist “racial community” (Volksgemeinschaft). Towards the end of 1935, Berta succeeded in procuring an invitation for Jacobsohn to the Soviet Union so that he could continue his research at the University of Sevastopol. Dora and her daughter (Fig. 15 ) were permitted to accompany him.

On the evening before her departure on 11 February 1936, Stencl organised a secret party in a Jewish restaurant in honour of the Russian Jewish poet Mendele Moicher Sforim (Scholem Jankew Abramowitsch, 1835/36–1917), which was disguised as a fictitious wedding celebration between Diamant and Stencl. Stencl described the evening later on that year, in a Yiddish journal published in Warsaw: “Dora Dymant sat at the head of the table, a professional actress and companion of Franz Kafka. She was ‘the bride’ and I was ‘the groom’. We were surrounded by several dozen members of our group, which no longer exists, who were still in Berlin, and a few other Yiddish language enthusiasts”. Dora read a chapter from Mendele’s story “The Wish Ring” (Dos wintschfingerl), and Stencl gave a talk about Mendele. “We sang old Yiddish songs, which made us, a group of Jews being persecuted in Nazi Germany, who were still able to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of our great classical author, joyful and merry”.[99] Diamant donated money to ensure that Stencl’s lecture could be printed in a special edition. The next day, Jacobsohn, Diamant and Marianne, under close observation by the Gestapo, departed for Moscow by train from Berlin.[100] During a brief stop in Będzin, Dora introduced her family to her daughter.

In Moscow, Diamant was amazed at the existence of the Yiddish-language State Jewish Theatre, founded in 1924, which she visited on one of her first evenings there. In February 1936, she applied for membership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Her application forms and the information about her life that they contained later formed the basis for reconstructing her life story. While Jacobsohn and Berta Lask moved to Sevastopol, Lutz and Dora remained in Moscow. The Stalinist show trials and two-way espionage among former KPD members who had immigrated from Germany put a strain on their marriage. When Marianne became severely unwell, contracting illnesses such as scarlet fever and infant tuberculosis, it became necessary to spend time in the milder climate of Sevastopol. In the spring of 1937, Diamant applied for permission to travel to Switzerland for the first time so that her daughter could visit a clinic there.

In June 1937, Diamant’s application for “transfer” from the German KPD to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was rejected due to political inactivity and her links to individuals who had since been arrested. Like all other foreign employees at the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute, Lutz Lask was dismissed, and soon received warnings regarding his earlier contact with former KPD members who had now been arrested. In March 1938, he was arrested by the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), accused of being a spy, sentenced a short time later, without a trial, to five years’ imprisonment in a labour and re-education camp, and deported to the Kolyma region of far-eastern Siberia. His connection to Dora, who still had only her German passport, was severed forever. Shortly afterwards, she and Marianne (Fig. 16 ) succeeded in escaping from the Soviet Union. How they managed to do so remains unknown.[101]

She was turned away at the Swiss border. In Germany, her name, “Lask, Dora, born Dymant” was on the Nazi regime’s wanted list. In the winter of 1938, she was able to enter the Netherlands, where she and Marianne found shelter with Lutz’ older sister Ruth and her husband, Ernest Friedländer, who had both emigrated from Berlin to The Hague in October 1933. Several attempts to reach Britain by ferry from the Hoek van Holland failed. In Friedländer’s apartment, she met the Dutch writer, Kafka researcher and anti-fascist Menno ter Braak (1902–1940, suicide following the German invasion). On 14 March 1939, Brod, who had published his first Kafka biography two years before, in which he had told the story of Diamant’s relationship with Kafka, succeeded in emigrating to Palestine from Prague.

Finally, on 16 March, Diamant received a temporary residence permit for Britain, and came back for Marianne at the end of August 1939. On 9 September 1939 and in the days that followed, her hometown of Będzin was destroyed by German troops. Her father had died the previous year. Other family members were deported to German labour and concentration camps. Of Diamant’s eleven siblings, just three survived the war, in a collection camp in Dachau.[102] At the end of May 1940, Diamant and her daughter were first interned in London, before being taken to the Isle of Man with over 3,000 other women and children from “enemy foreign countries”. She spent her free time organising theatre productions, concerts, lectures, and Yiddish readings.[103]

[99] Avrom-Nokhem Shtentsl: A Mendele-ovnt in Berlin, in: Literarisze bleter. Ilustrirte vokhnshrift far literatur, teater un ḳunst, Warsaw: Farlag B. Kletskin, 17/1/1936, page 33 f.; quoted here from the manuscript in the Archiv Bibliographia Judaica e.V., Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main; Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 234.

[100] Landesarchiv Berlin; ibid., page 235.

[101] Kathi Diamant 2013 (see Bibliography), page 237–252.

[102] Ibid., page 291.

[103] Ibid., page 253–271.