Polish poster art in post-war Germany

Mediathek Sorted

3. Good, inexpensive and in tune with the times: the reasons for success

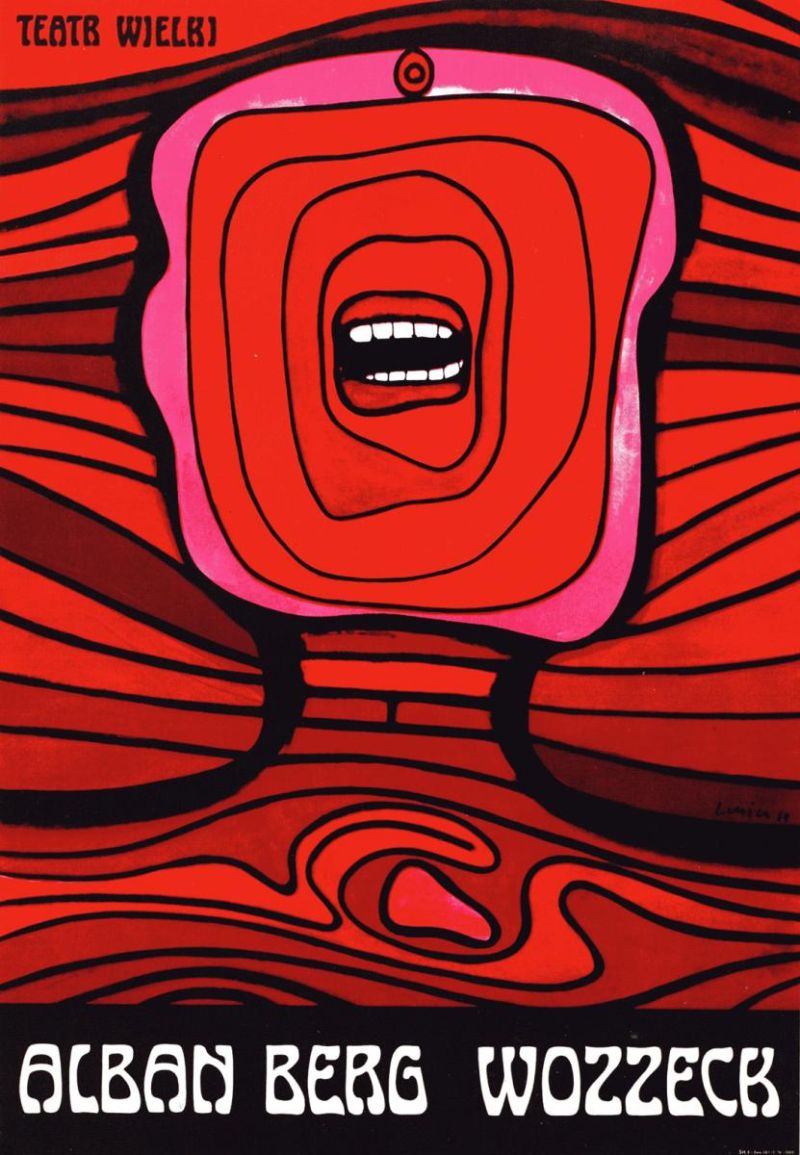

How can we explain the great popularity of Polish poster art in Germany and the large number of exhibitions, especially in the 1960s? Two decisive reasons have already been mentioned, namely their quality and reputation on the one hand and the general enthusiasm for Poland among Germans (the Polish wave) on the other. But other factors also played a role.

A very pragmatic reason is obvious: in comparison to exhibitions of paintings, poster exhibitions could be organised with much less financial and logistical expenditure. In addition, the posters were easy to obtain, there were distribution channels for them, and as a generally reproducible medium they were affordable: For example, at an exhibition in Frankfurt am Main in 1963, copies of Polish posters were available for 3 DM,[19] which at that time was equivalent to the price of a Suhrkamp paperback. Organising poster exhibitions was therefore the easiest and cheapest way to jump on the "Polish Wave", and the first private collections of Polish posters in the Federal Republic were created during this period. This also made them different to exhibitions of Polish painting and sculpture. During this time the latter were all organised jointly by Poland and West Germany and were funded from Poland. There were occasional purchases, but notable private or public collections of contemporary Polish painting did not exist in the Federal Republic at the time. With posters it was different. True, there were joint German-Polish exhibitions with Polish funding, but increasingly there were also exhibitions of posters from private, and later public collections.

There were, however, other reasons for the huge response. These included the specific topicality of posters as a medium. The "economic miracle" years were also a golden era for the advertising industry, when product and graphic design were playing an increasingly important role. It is no coincidence that documenta III presented its own section on industrial design and commercial graphics for the first time in 1964. Not surprisingly, it was not only the West German commercial graphics scene, but also and especially business and advertising experts who developed a penchant for Polish poster art during this period. They also began to promote Polish art, to collect Polish posters themselves and organise exhibitions (even if they did not advertise margarine or steel on Polish cultural posters).

Carl Hundhausen (1893-1977) a Krupp manager, was one of these culturally motivated advertising and business men. After 1945, when he was responsible for improving his company's image, Hundhausen became a close advisor to, and simultaneously a kind of cultural scout for Berthold Beitz, the CEO of Krupp. He was also one of the driving forces behind the various German-Polish joint exhibitions initiated and financed by Krupp.[20] In addition, Hundhausen held a professorship for "commercial advertising theory" at the Folkwang School of Design and was regarded as the father of "public relations" in Germany.

[19] Vcf. "Plakate — ohne Dekoration und Kitsch. Eine Ausstellung polnischer Werbegraphik im Studentenhaus", FAZ, 23.7.1963, p. 12

[20] For example, the major survey exhibitions “Polnische Malerei vom Ausgang des 19. Jahrhunderts bis zur Gegenwart” (1962) (cf. http://www.porta-polonica.de/de/node/260) and “Polnische Graphik” (1965), both in the Museum Folkwang in Essen. Hundhausen's active role can be seen, amonst others, in the archive material in the Krupp Historical Archive and the archive in the National Museum in Warsaw.