Polish poster art in post-war Germany

Mediathek Sorted

![ill. 22: Tomasz Sarnecki, Solidarność ill. 22: Tomasz Sarnecki, Solidarność - W samo poludnie [High noon], 4 June 1989](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/abb22.jpg?itok=ASCM67H8)

![ill. 23: Magazine ‘Jenseits der Oder’ [Beyond the Oder], Issue 6 ill. 23: Magazine ‘Jenseits der Oder’ [Beyond the Oder], Issue 6 - Published by the German Society for Cultural and Economic Exchange with Poland. Due to the unresolved border status from the perspective of the FRG, the title of the magazine was a provocation.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/abb23.jpg?itok=xaW1FoEX)

![ill. 24: Jan Lenica, Wizyta starszej pani [A visit from an elderly lady] ill. 24: Jan Lenica, Wizyta starszej pani [A visit from an elderly lady] - Announcement of a theatre performance](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/abb24.jpg?itok=a4ssK6p6)

"Fresh, aggressive, funny and intellectually challenging." Polish poster art in post-war Germany

1. Hymnic

Contemporary, fresh, modern and aggressive, witty and intellectually challenging", "boldly experimental", "avant-garde", "mentally stimulating and exciting" and completely free of "banality and kitsch": these were the words with which Erich Pfeiffer-Belli, the art critic on the Süddeutsche Zeitung, praised an exhibition of Polish poster art in March 1962, which was on show at the time in the Neue Sammlung in Munich.[1] (Fig. 1-3)

Pfeiffer-Belli's enthusiastic review was no exception. Rather, it was typical of practically all the public reactions to the exhibitions of Polish poster art in what was then West Germany. Exhibitions of Polish posters were a recipe for success. Those who organised them could be sure of a positive, if not hymnic, echo from the press. Their success was no accident. The high artistic level of Polish commercial graphics was recognized internationally. Polish poster art in particular was considered to be a leader in the field. It was a flagship of Polish art and enjoyed a legendary reputation in Germany. Significantly, it was unreservedly granted the status of an art form here , on a level with non-applied, free art and equally worthy of being presented in museums. This status simultaneously enhanced the value of commercial art in the Federal Republic of Germany.

West German critics praised the Polish posters for their "profound wit", their "sparkling zest" for irony, their "intellectually challenging" and "wonderfully disrespectful" treatment of historical styles and symbols. They praised their versatility, artistic boldness and experimental joy, at times their "drastic daring" and at others, their "Polish charm".[2] Some reviewers were close to singing hymns of praise to the planned socialist economy, because, as the director of the Neue Sammlung München Hans Eckstein put it laconically, "There, businessmen do not make posters".[3] Hence it was possible for commercial graphic artists to design their posters free of the constraints of the market and commerce. The fact that Polish poster art, even in the Stalinist era in the early 1950s, had been able to exploit creative freedoms that were at that time denied to non-applied art under the doctrine of socialist realism, made it additionally interesting.

These hymns of praise for Polish poster art are also remarkable from the point of view of historiography because they clearly invite us to revise a cliché of reception history. Prior to 1990 reviewers in the West were generally considered to have always treated art from Central and Eastern Europe with ignorance, arrogance, at best with paternalistic patronage, and to have viewed their avant-garde styles, if at all, as merely epigonal copies of Western currents. When it came to reviewing Polish poster art, especially in the 1960s, the opposite was decidedly the case. This was the art form that set recognized standards in the West and was warmly praised as a shining example for its own graphic artists. For example, Erich Pfeiffer-Belli wrote, “One could blush with shame," when comparing the "graphic poverty" of some West German posters with their Polish counterparts. And he strongly recommended that "German graphic designers take a close look at these works, not in order to copy them, but to be encouraged to experiment."[4]

The popular educational value of Polish poster art was also repeatedly emphasized not only on the Polish side, but also in West Germany. As art in public spaces, it was regarded as an educator of the people, so to speak. Indeed, a number of West German art critics and art educators were somewhat envious of Poland, where good taste could literally be learnt on the streets, on advertising columns and house walls. It was probably a gross overestimation of this particular medium, but that remains to be seen. (Fig. 4)

2. Historic: The original "Polish Wave" and beyond

The foundation stone for the triumphant advance of Polish poster art in the Federal Republic of Germany was laid at the beginning of the 1950s. In addition to magazines and individual book publications, exhibitions were by far the most important medium for its popularization. In 1950 an exhibition of Polish posters was shown throughout the Federal Republic of Germany, with stops in Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt/M., Nuremberg and Munich.[5] Amongst others, the journal "Gebrauchsgraphik", published a multi-page report complete with illustrations.[6]

A number of exhibitions of Polish graphic art were held in the following years, but the great boom began after the “Polish October” in 1956. The “Polish Spring in Autumn” not only made the country "fly into the hearts of the West", as Die Zeit wrote at the time,[7] but also sparked an unprecedented interest in contemporary Polish art and culture in the Federal Republic of Germany - a phenomenon that became proverbial among contemporaries as the so-called "Polish Wave". In view of the strained relationship between Poland and West Germany and the somewhat negative policies adopted by the West German government towards Poland, a fascination for the " thaw" in Poland with its cultural blossoming and apparent liberalism that were unique in the former Eastern Bloc played just as much a role as political and moral motives. The fact that frostier winds were already blowing once again through Polish cultural policies in the late 1950s, did not detract from the wave of enthusiasm for Poland in the Federal Republic. Until well into the 1960s, event calendars in West Germany were increasingly filled with listings of Polish music, literature, plays, films and art. There were Polish Weeks on the radio, in towns and cities featuring organised Polish "cultural days", and every few weeks there was an opening of an exhibition of Polish contemporary art somewhere in West Germany.

Exhibitions of Polish poster art formed an integral part of the Polish Wave and constituted a major part of all exhibitions of Polish art in the Federal Republic of Germany: Of the more than 100 exhibitions that can be traced back to 1970 in the Federal Republic of Germany, including West Berlin,[8] a good third were poster exhibitions. Many of them were touring exhibitions, which were shown in several cities in the Federal Republic of Germany, so that the number of venues is much higher.

The following overview of exhibitions of Polish poster art, which took place in 1964-66, provides an impression of their extent.[9] (Fig. 5)

As can also be seen from the list, exhibitions in West Germany were held wherever possible: in galleries, museums and art halls as well as in hotel and theatre foyers, city libraries and department stores.[10] The spectrum of organizers and organisers, which included not only cultural institutions but also student initiatives and private collectors, like two examples from Darmstadt, was correspondingly heterogeneous:

In June 1964, the local student body in Darmstadt organized an exhibition at the Technical College, which was reviewed not only by the Darmstadt-based student newspaper, but also by the local press and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.[11] The introductory lecture was given by the renowned and energetic Warsaw academy professor and poster artist Józef Mroszczak (1910-1975), who was a guest professor at the Folkwang School of Design in Essen (I shall return to this later) and in Darmstadt. The audience was very taken by "his chivalrous appearance and [the] elegance of his lecture".[12]

A few months later, in October 1964, the Darmstadt department store Henschel & Ropertz joined the market (now the Henschel fashion house) and enhanced its sales of ready-made goods with "masterpieces of Polish poster art": in this case, with posters from the private collection of the journalist, Hans-Joachim Orth.[13] (Fig. 6-7)

What kind of posters did the West German public see at the exhibitions? Posters for cultural events, i. e. plays, films, exhibitions, concerts, opera and circus posters made up the majority of the total, thereby turning Polish cultural posters into the epitome of Polish poster art. Political posters, on the other hand, were, unsurprisingly, the exception rather than the rule in the exhibitions and were usually limited to rather discreet and uncompromising designs for First of May or for the Polish national holiday on 22nd July (fig. 8). Tourist posters, which existed in Poland in large numbers (e. g. the well-known posters of the airline LOT), and occupational safety posters, which were widespread in Poland, only played a marginal role at the West German exhibitions.

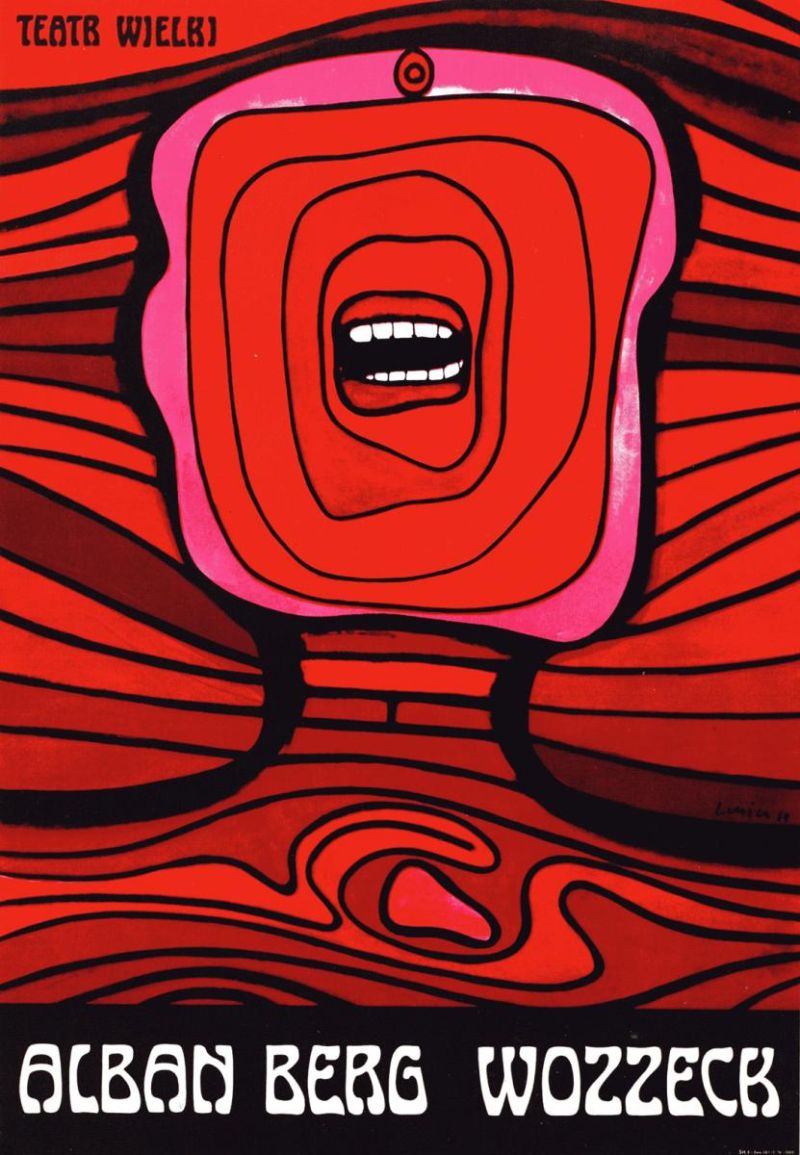

Alongside from the old masters Henryk Tomaszewski (1914-2005) and Józef Mroszczak, Roman Cieślewicz (1930-1996) and Jan Lenica (1928-2001) were among the most popular and most exhibited Polish poster artists in West Germany in the 1960s. Lenica's poster for Alban Berg's opera "Wozzeck" became an icon of Polish poster art and is still included in every anthology. (Fig. 9-14)

Jan Lenica is also perhaps the Polish poster artist who has most left his mark on the collective German memory, if not by name, then by his unmistakable, concise formal language. As early as the early 1960s, he developed his psychedelic and art nouveau Pop Art look from interlocking forms, and this became his trademark. (Fig. 15-17)

In addition to the exhibitions, periodicals and book publications also served to mediate the work in the Federal Republic of Germany. The Bund deutscher Gebrauchsgraphik (Federal Association of German Commercial Artists) was particularly committed to publishing regular reports on Polish poster art in its journal "Gebrauchsgraphik". The same applies to the legendary monthly magazine "Polen" published by the Warsaw Polonia publishing house; it was released in several European countries, including a West German and an East German edition, and enjoyed an extensive readership in the Federal Republic due to its refreshing presentationt. (Fig. 18)

In addition, there were various book publications, including a volume entitled "Polish Poster Art" by Józef Mroszczak, which was published in German in 1962. It contained introductory contributions by Jan Lenica and Białostocki and used examples from more than 40 artists to portray a broad panorama of contemporary Polish poster art.[14]

Towards the end of the 1960s the Polish Wave slowly faded in Germany. By contrast, the Warsaw Treaty was signed in December 1970 as part of the New Eastern Policy under Willy Brandt, which laid the foundations for the normalisation of German-Polish relations and the establishment of diplomatic relations. Cultural contacts were thus also put under new auspices and this triggered a new, if small, Polish wave.

Polish posters and poster artists continued to enjoy unbroken popularity (although, in the eyes of some critics, their quality had "passed its zenith")[15], and posters continued to be collected by museums. Thus, one of the first exhibitions at the newly founded Deutsches Plakatmuseum in Essen in 1971 was devoted to "Four Polish poster artists", namely Roman Cieślewicz, Jan Lenica, Józef Mroszczak and Henryk Tomaszewski.[16] In 1984 the major retrospective "Post-War Polish posters" in the New Munich Collection was put together entirely from the museum's own stocks.[17]

New names and new visual languages were added in the 1970s and 1980s. In particular, posters by Franciszek Starowieyski (1930-2009) were in demand during this period. (Fig. 19-20)

In addition, some of the poster artists who had been regularly represented at exhibitions since the late 1950s and early 1960s remained present in Germany, above all Roman Cieślewicz[18] and Jan Lenica. Lenica in particular remained closely associated with the Federal Republic of Germany. By this time he had made a name for himself there not only as a poster artist, but also as a cartoon film artist, stage designer and children's book illustrator, for which he was awarded numerous prizes, including the 1965 Federal Film Prize and, in 1980, the poster prize of the city of Essen. He was also involved in the "Olympia" poster edition for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich (see fig. 17 above). In 1979 he was appointed to the newly awarded chair for animated film at the Kassel College of Art. And he also left his mark on the West German landscape of commercial graphics as a designer of postage stamps for the Deutsche Bundespost (for example, the International Peace Year 1986). (Fig. 21)

3. Good, inexpensive and in tune with the times: the reasons for success

How can we explain the great popularity of Polish poster art in Germany and the large number of exhibitions, especially in the 1960s? Two decisive reasons have already been mentioned, namely their quality and reputation on the one hand and the general enthusiasm for Poland among Germans (the Polish wave) on the other. But other factors also played a role.

A very pragmatic reason is obvious: in comparison to exhibitions of paintings, poster exhibitions could be organised with much less financial and logistical expenditure. In addition, the posters were easy to obtain, there were distribution channels for them, and as a generally reproducible medium they were affordable: For example, at an exhibition in Frankfurt am Main in 1963, copies of Polish posters were available for 3 DM,[19] which at that time was equivalent to the price of a Suhrkamp paperback. Organising poster exhibitions was therefore the easiest and cheapest way to jump on the "Polish Wave", and the first private collections of Polish posters in the Federal Republic were created during this period. This also made them different to exhibitions of Polish painting and sculpture. During this time the latter were all organised jointly by Poland and West Germany and were funded from Poland. There were occasional purchases, but notable private or public collections of contemporary Polish painting did not exist in the Federal Republic at the time. With posters it was different. True, there were joint German-Polish exhibitions with Polish funding, but increasingly there were also exhibitions of posters from private, and later public collections.

There were, however, other reasons for the huge response. These included the specific topicality of posters as a medium. The "economic miracle" years were also a golden era for the advertising industry, when product and graphic design were playing an increasingly important role. It is no coincidence that documenta III presented its own section on industrial design and commercial graphics for the first time in 1964. Not surprisingly, it was not only the West German commercial graphics scene, but also and especially business and advertising experts who developed a penchant for Polish poster art during this period. They also began to promote Polish art, to collect Polish posters themselves and organise exhibitions (even if they did not advertise margarine or steel on Polish cultural posters).

Carl Hundhausen (1893-1977) a Krupp manager, was one of these culturally motivated advertising and business men. After 1945, when he was responsible for improving his company's image, Hundhausen became a close advisor to, and simultaneously a kind of cultural scout for Berthold Beitz, the CEO of Krupp. He was also one of the driving forces behind the various German-Polish joint exhibitions initiated and financed by Krupp.[20] In addition, Hundhausen held a professorship for "commercial advertising theory" at the Folkwang School of Design and was regarded as the father of "public relations" in Germany.

IIt is also thanks to him that, in 1964, Professor Józef Mroszczak was able to come to Essen as a guest professor at the Folkwang School, financed by a scholarship from the Krupp company. Mroszczak was head of the department for commercial graphics at the Warsaw Academy of Art, a luminary of Polish poster art and generally a busy figure in the cultural establishment in Poland. There was hardly any Polish poster exhibition in the Federal Republic in which he was not somehow involved. His sponsor Carl Hundhausen, in turn, was invited to speak at the 1st International Poster Biennale in Warsaw in 1966, whose guiding spirit was Mroszczak.[21] Some time later he was one of the co-founders of the German Poster Museum in Essen,[22] where Mroszczak's poster art was honoured on several occasions including an exhibition in 1971 and, posthumously, in a major retrospective in 1978.[23]

But Polish posters were not only artistically pioneering, easily available and in line with the spirit of the time. They also had a moral bonus – something which once again demonstrates that the Cold War division into “good and bad” culture did not always remain strictly behind the Iron Curtain: The economic miracle years in the Federal Republic of Germany were not only a time of consumer spending, but also of consumer criticism, cultural pessimism and scepticism towards commercialization, mass culture and the cultural industry. In this context, the American film industry, and its Hollywood posters, embodied one of the enemy images par excellence. It became the epitome of showmanship, loud-mouthed vulgarity and kitsch. Polish poster art arrived precisely at the right time as a positive counter-image. It was celebrated as fresh, unspoilt, original, unbounded by commerce, and only committed to artistic criteria. Seen in such a light it became a sort of "noble savage" in the commercial poster branch. Against this backdrop, however, there is some irony in the fact that an American revolver hero was revived in a poster, which was to become one of the most iconic in recent Polish history. (Fig. 22)

4. Political matters

As unanimous as the enthusiasm for Polish poster art was in Germany, the exhibitions were not always politically uncontroversial, certainly not from the point of view of the Bonn authorities and before the Warsaw Treaty of 1970. However, this depended less on the contents of the exhibition and the daily fluctuations in the atmosphere of Polish-West German rapprochement than on the organizers and their political colour.

A literal red rag for the federal authorities was the "German Society for Cultural and Economic Exchange with Poland" that was near to the KPD (Communist Party of Germany). Founded in Düsseldorf in 1950 as a West German offshoot of the East German Helmut-von-Gerlach Society,[24] it continued to develop its considerable activities and did everything in its power through events, exhibitions and its journal Jenseits der Oder (Beyond the Oder) to spread a positive image of Poland in the Federal Republic – much to the displeasure of many organisations, not least those people who had been expelled from Poland.[25] (Fig. 23)

Until the mid-1950s, it was practically the only organization that hosted exhibitions of Polish art in the Federal Republic of Germany, although it was often able to attract the cooperation of a wide variety of cultural institutions, such as in the provision of exhibition spaces. The society also organised the aforementioned touring exhibition of Polish posters in 1950. Whilst from a Polish point of view it was something like an unofficial West German friendship society, it was regarded by the Federal Republic of Germany as a communist camouflage organisation – not only keeping the expellee associations on their toes, but also the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and the Foreign Office, which had "most powerful objections" to the association.[26] Many of their Polish poster exhibitions in Germany had a correspondingly difficult status. In some cases, openings were disturbed by compatriot groups, and exhibitions were banned in advance by the police in order not to endanger law and order.

The fact that the circle of exhibition initiators and organisers expanded from the mid-1950s onwards and the fact that more and more 'politically harmless' activists were engaged in Polish-Western German cultural exchanges was highly welcome in Bonn, where it was vital to counter the quasi-monopoly status of the German Society for Cultural and Economic Exchange with Poland.[27] Hence, exhibitions were not only allowed permitted after it was sure that the Society was not involved.[28] The Foreign Office also attempted to deliberately aid such alternative promoters in order to create a counterweight to the Society. However they had to accept the fact that the diversification of actors and networks behind the exhibitions was also highly welcome amongst the authorities in Warsaw. In the fight for public opinion, its aim was to expand its spheres of influence and reach the widest possible audience in Germany with Polish cultural exports.

But politically suspect organisers were not the only ones to turn Polish poster exhibitions into a stumbling block in the 1950s and early 1960s. At a time when Bonn was still a long way off from its "New Eastern Policy" and the recognition of the Oder-Neisse border, sensitive border issues did not stop at Polish poster art. In 1962, for example, the organisers of an exhibition of Polish theatre posters and stage designs in Schleswig were asked to reconsider their choice of exhibits after it became known that they would also be documenting Polish "theatre life in the Oder-Neisse areas". [29] In another case, the Foreign Office only agreed to a tour of Germany by the Wroclaw Pantomime Theatre on condition that the name of the city did not appear on posters and other announcements. The Foreign Office therefore suggested that the ensemble be renamed the "Henry Tomaszewski Pantomime Theatre" – after the founder and director of the theatre Henry Tomaszewski, not to be confused with the poster artist of the same name – instead of the "Wroclaw Pantomime Theatre". Correspondingly the fact that one of the posters was then printed with the ensemble name "Pantomime Theater Breslau" caused considerable annoyance in the Federal Foreign Office.[30]

As these examples show, even supposedly non-political and harmless cultural posters were political dynamite if they touched on political taboos. However, the growing popularity of Polish poster art in Germany was hardly affected by official concerns, reservations and safety precautions.

5. "Polish Poster Schools"?

This success was reflected not least in the fact that in the Federal Republic of Germany too, people soon only spoke of the "Polish poster school", a name which is still used today. When, how and through whom the term came into circulation is as controversial as the question of what the Polish poster school as such is supposed to mean. And there are already various suggestions regarding the time frame. The term is also problematic or at least misleading insofar as it suggests a consistency and coherence that scarcely existed. Not only do worlds seem to lie between the folkloric-humoristic operetta posters of someone like Józef Mroszczak in the early 1960s and the posters of an artist like Starowieyski in the 1980s (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 20). It is rather the case that Polish poster art in the post-war period was always characterized by a juxtaposition of the most varied positions and great formal and technical diversity, both amongst the artists themselves, who often developed very distinct individual styles, and also within their own oeuvre. Decorative ornamentation alternated with surrealistic symbolism, elements of collage stood alongside painterly solutions, photographic alongside typographical elements, pleasure and playfulness alongside disturbing and cryptic elements. Equally striking is the versatility and variety of the individual artists. Compare Jan Lenica's Woyzeck poster (Fig. 14) with his Max-Ernst-related design in 1958 for Friedrich Dürrenmatt's "The Visit" (Fig. 24) or Leszek Hołdanowicz's posters, Pasażerka, (1963) and Bariera, 1966. (Fig. 25-26)

This inventiveness is also a basic reason why Polish posters enjoyed such a positive status amongst contemporaries: equally the uniform propaganda posts of Soviet origin and the uniform look from Hollywood. And this is perhaps the reason why people's talk of a "Polish post school" seemed so plausible.

However we should also take into consideration the fact that Polish poster artists did not work in isolation for they were also internationally networked. This is another reason why the term "Polish poster school" should be used with caution, even if today nobody would think of looking for anything essentially Polish in the posters. Cieślewicz, for example, moved to Paris as early as 1963. Jan Lenica had also been active in France since the 1960s, and later in Kassel and West Berlin. Józef Mroszczak had been travelling repeatedly to the Federal Republic of Germany since the 1950s, either as a guest lecturer or for exhibition openings. Conversely, exhibitions of foreign poster art took place in Poland itself - including in 1957 an exhibition of West German poster artists.[31] Not least, the series of "International Poster Biennales" in Warsaw since 1966 have further contributed to internationalisation. (Fig. 27)

If the question of what constitutes Polish poster art makes any sense at all, it would therefore have to include questions of international interdependence, transfer relationships and networks.

Regina Wenninger, December 2017