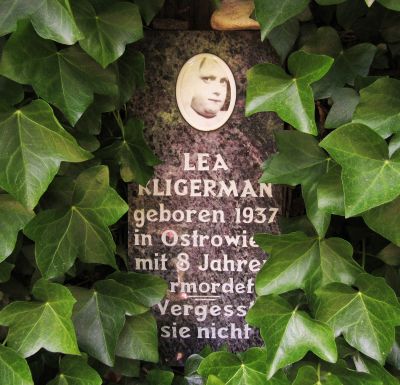

The children of Bullenhuser Damm

Mediathek Sorted

Heißmeyer, who initially managed to escape detection after the war, ran his own medical practice in the GDR until 1963 and was also the director of the private Klinik des Westens in Magdeburg. He was arrested in Magdeburg on 13 December 1963. In the preliminary hearings prior to the main trial, during which Dr. Szafrański also issued witness statements, Heißmeyer admitted that: “I knew that the serum was toxic, but I wanted to find out more about immunobiological behaviour in humans. I was aware that such experiments with a virulent serum were never permitted to be conducted on humans. However, on the other hand, I also knew that experiments on guinea pigs were of no use, since by nature, these animals do not contract tuberculosis. That is why I took my experiments to a concentration camp, where a sufficient number of test subjects were available, and where I was not required to take their welfare into account. I was aware of the risks arising from my experiments, and of their potentially lethal consequences, but I wanted to publish an academic paper. [...] To me, the prisoners at Neuengamme concentration camp, and the children brought there at my request in the autumn of 1944, were no more than test subjects...”[12]. After Heißmeyer realised in the autumn of 1944 that his attempts to cure tuberculosis among adults through artificial infection had failed, and that instead, the physical state of the prisoners had worsened, he “abandoned the experiments and requested that 20 children be brought, on which I conducted experiments related to immunisation against TB using the same serum, as well as to determine any already existing immunity”.[13]

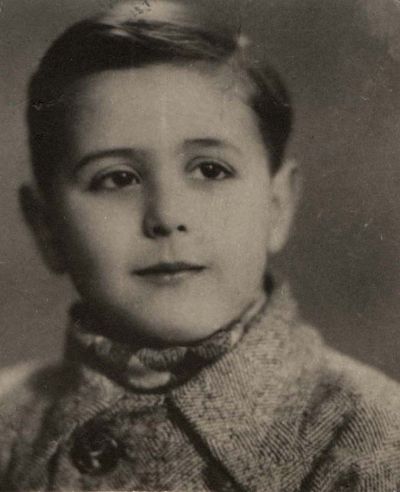

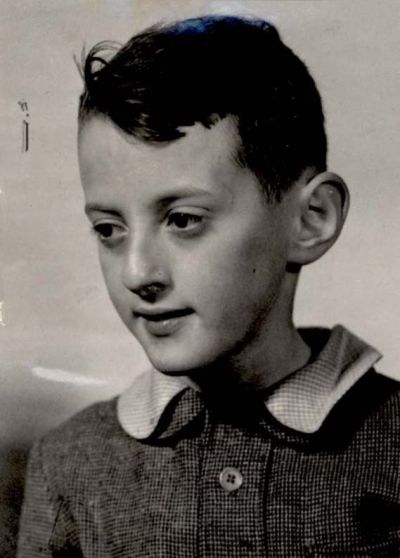

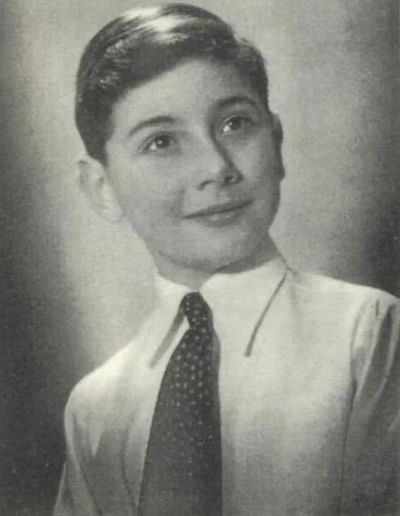

In an interview transcript from 1956, the dentist Dr. Haja (Paulina) Trocki-Musnicki, who was born in Kishinev (today: Chișinău) in 1905, who studied in Belgium and who was deported from there to Auschwitz as a resistance fighter, reported on the transportation of the children from Auschwitz to Neuengamme on 28/29 November 1944. The interview was stenographed in Israel by the contemporary historian Kurt-Jacob Ball-Kaduri, originally from Berlin, for the Yad Vashem Remembrance Center: “From September or October 1944, when it [the war] was already nearing its end, children arriving at Auschwitz were no longer killed (or not all of them?). When I arrived in August, all of the children from my train were discarded. But afterwards, they remained alive, and at the end of the year, there were around 300 children in Auschwitz, in one block. [...] The children had it good, since all the adults somehow took care of them, i.e. all the prisoners. One day at midday, I was called to the camp leader, and was told that I would have to board a train with the children, to accompany them. Apart from me, there were three nurses, one of which was a laboratory assistant from Hungary. There were ten boys and ten girls, aged between six and twelve, all Jews, but from all kinds of different countries. Two of them were from Paris. I asked why the children were being sent away. I was told: all children without parents. I learned from the children that, in the labour camp, many of the parents had been sent away on trains”.[14]

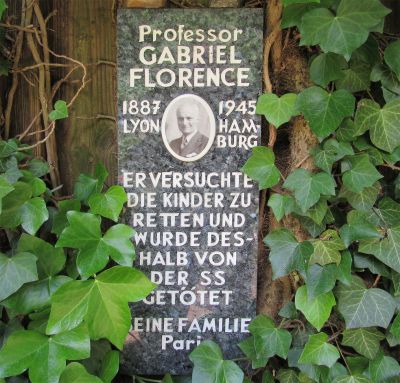

The children, who were accompanied by the SS, were transported in a special train car, which was hitched to a normal passenger train. It travelled from Auschwitz right through Poland, and on to Neuengamme via Berlin. At 10 pm on 29 November 1944, it arrived at a side track at Neuengamme which led straight into the camp. During the journey, the children were “excellently” cared for, according to Trocki, and were given milk and chocolate. When they arrived, she witnessed someone beginning to cry when he saw the children. A Belgian medical student who worked in the pharmacy was afraid that the children would be used for experiments. However, there was a French doctor in the camp who tried to save the children. After that, though, she didn’t see the children again. They were taken to the barracks where the experiments were due to take place, and given bunk beds there. Dr. Trocki was later moved to the Helmstedt-Beendorf women’s satellite camp. The three nurses on the train, two of whom were Poles, according to a witness, “headed towards the bunker” with their few possessions.[15] Later, another witness in the main Neuengamme trial reported that four Polish women were executed in the bunker at Neuengamme[16]. However, nothing is known of their identity.

[12] Statement by Kurt Heißmeyer in custody, 20/3/1964, BStU file [Federal Commissioners for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic, Die Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik], MfS [Ministry of State Security, Ministerium für Staatssicherheit] 8924/66, Volume 152; quoted from: Medizinische Experimente an Häftlingen (see footnote 10); see also: Der Prozess gegen Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer. Dokumente, at: Gedenkstätte Bullenhuser Damm (see Online), http://media.offenes-archiv.de/03_gruen_01.04.11_klein.pdf

[13] Interrogation of Heißmeyer in custody on 11/3/1964, Sheet 108 of the court files; quoted from Schwarberg: SS-Arzt 1997 (see Bibliography), page 37

[14] Interview transcript from 30/12/1956, document 01/166 - 117/37 - 1066, Yad Vashem; partial copy online: http://media.offenes-archiv.de/beige_VerfolgungDeportation_04.04.11_klein.pdf; Transcript at Geteuigen. Breendonk - Mechelen - Andere kampen - Bij derden, http://www.getuigen.be/Getuigenis/3den/Ball-Kaduri/tkst.htm

[15] Schwarberg: SS-Arzt 1997 (see Bibliography), page 39 f.

[16] Curiohaus-Prozess 1969 (siehe Bibliography), Volume I, page 188. Citations in Schwarberg: SS-Arzt 1997 (see Bibliography), page 40