The children of Bullenhuser Damm

Mediathek Sorted

“The children all spoke broken German with a Polish accent. After a while, Frahm came in and said that the children should remove their clothes. I saw that they were rather reluctant to do so, and told them that they were being asked to undress so that they could be vaccinated against typhus. I then took Frahm out of the room so that the children couldn’t hear what we were saying, and asked him quietly what was going to happen to them. Frahm was also very pale, and said I should hang the children.”[1]

The SS Hauptsturmführer and concentration camp medic Dr. Alfred Trzebinski, who made this statement on 24 April 1946 during the Hamburg Curiohaus trial and who participated in the murders, was all too familiar with the Polish accent of his victims. He himself was born in 1902 in Jutroschin in the Prussian province of Posen (today: Jutrosin, Greater Poland Voivodeship), which had been given to Poland in 1919/20 in the Treaty of Versailles. He also had a Polish father. However, not all of the children came from Poland. Of the twenty Jewish children who were hanged in the former school on Bullenhuser Damm in the Rothenburgsort district of Hamburg, one came from Italy, two from the Netherlands, one from Slovakia, two from France, and 14 from Poland. All of the children had been separated from their parents in the Auschwitz concentration camp in the autumn of 1944, selected for medical experiments, and taken to the Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg.

How the children were brought to the Auschwitz concentration camp

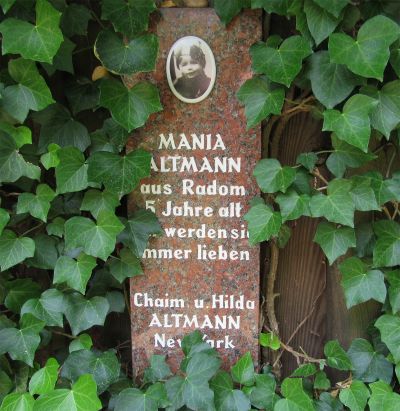

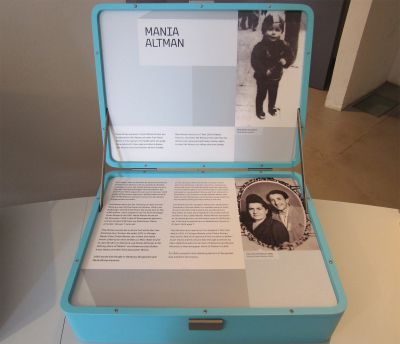

Mania Altman, born on 7 April 1938 in Radom, Poland, was the daughter of Pola and Shir Altman, a shoemaker. From the spring of 1941, she and her family lived in the ghetto established in Radom by the German occupiers. Her parents, aunts, and uncles, who also lived in the ghetto with their families, were sent to work at different camps. In the summer of 1944, Mania and her parents were deported to Auschwitz via the nearby Pionki forced labour camp, which served a gunpowder factory. Her father was then sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp, where he was murdered during the final weeks of the war. In August 1944, Mania was separated from her mother in Auschwitz. At that time, she was six years old. Pola Altman was deported to a satellite camp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp in October, was liberated in 1945, and emigrated to the US in 1951. Right up until her death in 1971, she never found out what had happened to her daughter.

Lelka Birnbaum, who was born in Poland in around 1933, is known only from a list of names published by the Danish doctor and prisoner at Neuengamme concentration camp, Dr. Henry Meyer, in the book, “Rapport fra Neuengamme”, written in collaboration with the Swedish doctor, Gerhard Rundberg. The list contained her surname, gender, and age. Her full name also appears on the cover sheet of an X-ray image and on a photograph used to document the medical experiments that were conducted on her. She was probably eleven years old when she arrived in Auschwitz.

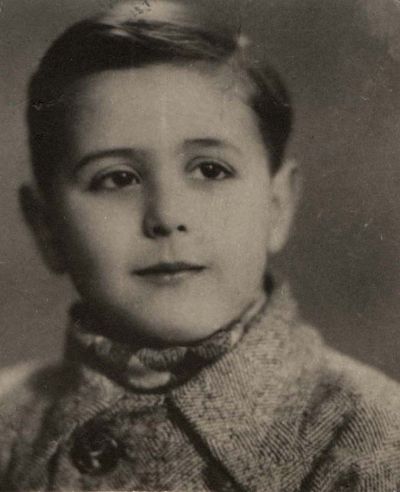

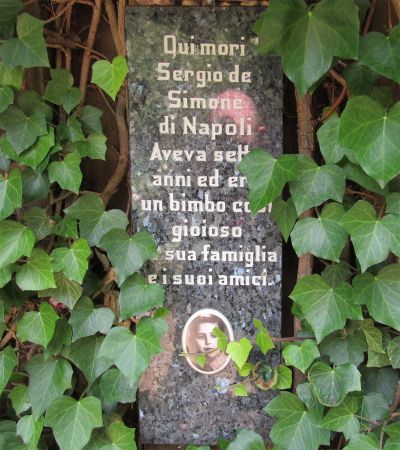

Sergio De Simone (Fig. 1 ) was born in Naples on 29 November 1937. His mother Gisella, née Perlow, who came from Fiume/Rijeka, was Jewish, while his father, Edoardo De Simone, who was a ship’s officer, was Catholic. After the Allies bombed Naples, the family moved to Rijeka in the summer of 1943. It was there that Sergio, his mother and, seven other family members, including his cousins Alessandra and Tatiana, were arrested in March 1944. On 4 April 1944, they were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp via the Risiera di San Sabba concentration and collection camp near Trieste. At that time, Sergio was six years old. His father was taken to Dortmund as a forced labourer. His mother was liberated from the Ravensbrück concentration camp; his two cousins also survived. His parents were reunited in Italy. Until her death in 1984, his mother never lost hope that her son might still be alive.

Surcis Goldinger, who was born in Poland in 1934 or 1935, is noted on the list published by Henry Meyer in “Rapport fra Neuengamme”, which gives her surname, age, gender, and Poland as her place of origin. A girl with her name is also listed on a transport train that travelled to Auschwitz from a forced labour camp in Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski in Poland on 3 August 1944. At that time, Surcis was around ten years old.

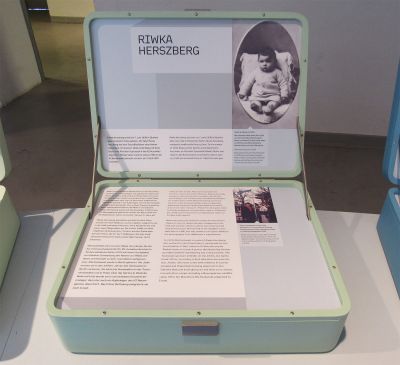

Riwka Herszberg, born on 7 June 1938 in Zduńska Wola in the Polish voivodeship of Łódź, was the daughter of Mania and Mosze Herszberg, the head of a small textile factory. In the summer of 1944, the family was deported to Auschwitz concentration camp via the collection camp established by the Nazis in Piotrków. In Auschwitz, Riwka and her mother were interned in the women’s camp. Her father was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp in January 1945, where he was murdered three months later. Riwka was transported to Neuengamme five days after her mother was taken to a satellite concentration camp in Lippstadt on 23 November 1944. At that time, she was six years old. Mania Herszberg survived the war and later emigrated to the US.

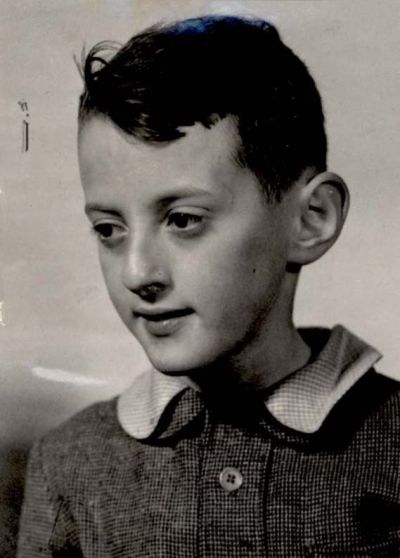

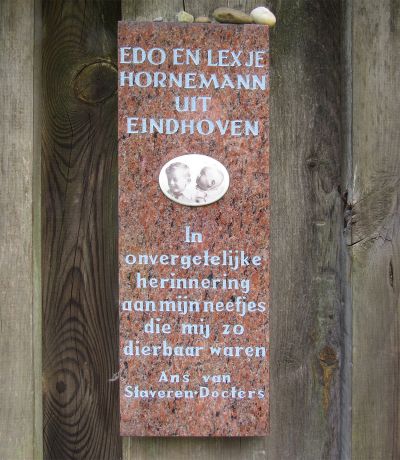

Alexander and Eduard Hornemann (Figs. 2 , 3 ) came from Eindhoven in the Netherlands. Eduard was born on 1 January 1933, Alexander on 31 May 1936. Their father, Carl Philip Hornemann, worked at the electrical and radio appliance company Philips. From 1941, their mother, Elisabeth, and her sons went into hiding on a number of different farms. When the approximately 100 Jewish employees of the company were deported to the Herzogenbusch concentration camp near Vught in 1943, Elisabeth followed her husband with the children. The family were transported to Auschwitz concentration camp on 3 June 1944. At that time, Eduard was eleven, and Alexander was eight years old. After their mother died of typhus in September, Eduard and Alexander were moved to the children’s barracks and taken to Neuengamme on 28 November 1944. Their father was transferred to Dachau concentration camp and died on 21 February 1945 while being transported to the concentration camp at Sachsenhausen.

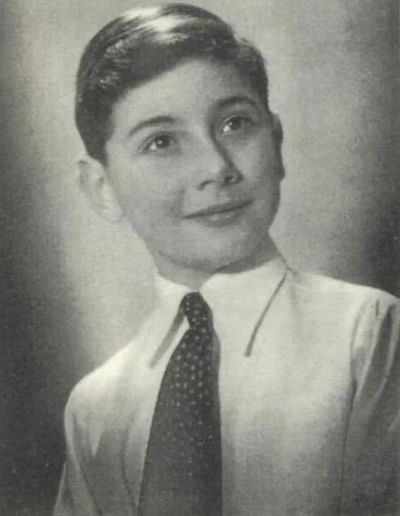

Marek James (Fig. 4 ) from Radom in Poland was born on 17 March or 17 April 1939. After the ghetto in Radom was established by the German occupiers in March 1941, he and his parents Adam and Zela were forced to live there. Like Mania Altman’s family, they too were taken to the Pionki forced labour camp in 1943. From there, they were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp in the summer of 1944, where Marek was separated from his mother. At that time, he was five-and-a-half years old. His mother survived the war in the women’s satellite camp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp in Jiřetín in Czechoslovakia. His father also survived, in the satellite camps of Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Glöwen and Rathenow. After the war, the couple lived in southern Germany, had another son, and emigrated to the US in 1949.

Walter Jacob Jungleib (Fig. 5 ) was born on 12 August 1932 in Hlohovec, Slovakia. His parents were the goldsmith and watchmaker Arnold Jungleib and his wife Malvina, née Frieder. He had a sister, Grete, who was two years older. His parents owned a jewellery shop. From 1942 onwards, the family were forced to move several times to escape the persecution of the Jews. In October 1944, they were taken to the Sered’ transit camp in western Slovakia and from there to Auschwitz, where they were separated. At that time, Walter was twelve years old. His father died in the Mauthausen concentration camp. Like Riwka Herszberg’s mother, Walter’s mother was transferred to a satellite camp in Lippstadt on 23 November 1944, where all trace of her is lost. Grete survived the Holocaust and lives near Tel Aviv in Israel.

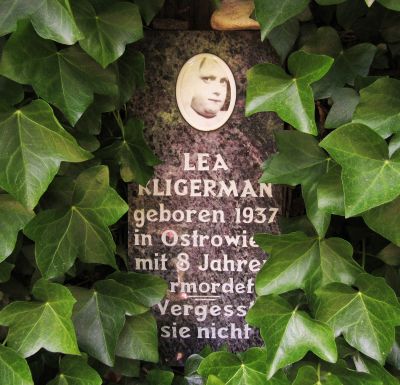

Lea Klygerman (Kligerman) was born on 28 April 1937 in Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski in Poland. Like Surcis Goldinger, she and her younger sister Rifka, together with her mother Ester, née Herczyk, were deported from the Nazi forced labour camp in the town to Auschwitz on 3 August 1944. Lea was seven years old. On 28 November of that year, she was taken to Neuengamme concentration camp. Nothing is known of what happened to Rifka. Her father, Berek Klygerman, was deported to Auschwitz from the forced labour camp at Bliżyn, a satellite of the Majdanek concentration camp forty kilometres south-west of Radom. In October 1944, he was taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp and later to Buchenwald concentration camp, where he died in February 1945. Ester Klygerman survived and returned to Poland after the war. She emigrated to Israel in the 1970s, where she re-married.

Georges André Kohn (Fig. 6 ) was born on 23 April 1932 in Paris in a family related to the Rothschild banking dynasty from England. His mother Suzanne (1895–1945) née Nêtre, was the daughter of a tobacco factory owner and was related by marriage to the Rothschild family via a first cousin. His father, Armand Edouard Kohn (1894–1962), a descendant of one of the oldest and most established Jewish families in France, was a banker and, from 1940, Secretary General of the Hôpital Fondation Adolphe de Rothschild and managing director of the Hôpital Rothschild, the first Jewish hospital in Paris.[2] During the German occupation, ill people from the Drancy collection camp were sent to this hospital before being transported to the death camps. The family had three other children, Antoinette, Rose Marie, and Philippe, who at the time of deportation were 22, 18, and 21 years old respectively. The family home was shared with the 72-year-old grandmother Marie Jeanne, née Weisweiler, from Frankfurt/Main. In 1942, the mother, Suzanne, converted to Catholicism together with the children in an attempt to escape persecution by the Nazis. Even so, in July 1944, the family was arrested together with a group of prominent Jews who until that time had not been exposed to such great danger as other members of the Jewish community. They were interned in Drancy transit camp and on 17 August, just one week before the liberation of Paris, they were taken to Germany on the last transport train. On the train, in which SS Hauptsturmführer Alois Brunner and his military personnel were also travelling, the group of 51 deportees were used as hostages. While the train was still travelling in French territory, Georges André’s siblings, Rose Marie and Philippe, together with 30 others, managed to escape from the train and were hidden in Saint-Quentin until France was liberated. His father, Armand, was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, was liberated in April 1945, and returned to France. The remaining family members were transported onwards to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Some time later, Suzanne Kohn and her daughter Antoinette were taken to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where they died shortly afterwards. The grandmother Marie Jeanne was killed in a gas chamber after arriving in Auschwitz. According to an account later given by a fellow French prisoner, after arriving at the camp, Georges André was taken to work camp D and was employed as a transport worker for the rolling carts. Before his mother was taken from the camp, he was able to remain in contact with her by writing secret letters. At that time, he was twelve years old.

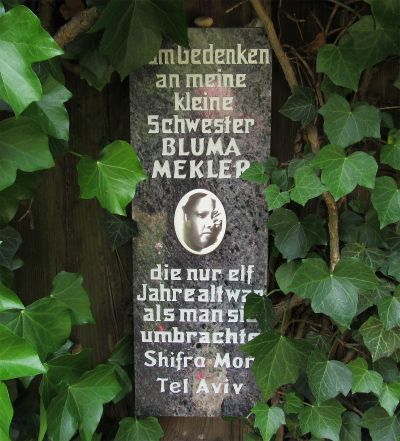

Bluma (Blumel) Mekler was born in Sandomierz, Poland, in 1934. Her parents, Sara, née Taitelbaum, born in 1903 in Koćmierzów in the district of Sandomierz, and Herszel/Hershel Mekler, born in 1889 in Sandomierz, ran a trade in agricultural supplies. Her father was also taught religion in the cheder, a primary school class in which boys learned about Jewish religion and culture. Blumel had two sisters, Gita and Szifra, and two brothers, Berl and Alter. After the closed ghetto was established by the German occupiers in Sandomierz in June 1942, the family were forced to move there. When the ghetto[3] was brutally liquidated on 29 October 1942 and 4 January 1943, the family became separated. During a raid in October 1942, her sister, Szifra/Shifra fled at the insistence of her mother. She was hidden by Polish neighbours until the end of the war, and emigrated to a kibbutz in Israel in 1947 after being taken in by a Jewish orphanage in Lublin.[4] Her brother Alter, who was born in 1929, was taken to Auschwitz via Majdanek concentration camp. He managed to survive, and was reunited with his sister Shifra in Israel. It is not known how Bluma Mekler came to Auschwitz, or what happened to her parents and other siblings. She too was taken to Neuengamme on 28 November 1944. She was ten or eleven years old.

Jacqueline Morgenstern (Fig. 7 ) was born in Paris on 26 May 1932. Her mother, Suzanne, was a secretary; her father, Charles, owned a hairdressing salon together with his brother, Leopold. After the occupation of Paris by the German Wehrmacht, the Morgenstern brothers were forced to relinquish their salon to non-Jews. In 1943, the family fled to Marseille in Vichy France. There, they were arrested and taken to Drancy collection camp near Paris. On 20 May 1944, they were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp, where Suzanne was murdered. On 28 November 1944, Jacqueline and the other children were transferred to Neuengamme. She was twelve years old. When Auschwitz was cleared, her father was taken to Dachau concentration camp on the last transport train. He died there after liberation in May 1945.

Eduard Reichenbaum was born in Katowice, Poland, on 15 November 1934. He was the son of Sabina and Ernst Reichenbaum, who had another son, Jerzy, who was two years older. His father worked as an accountant in a German-language publishing house. Shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War, the family moved to Piotrków, the home of his grandparents. In 1943, they were interned by the German occupiers in the Bliżyn forced labour camp to the south-west of Radom, where Eduard and Jerzy were put to work producing socks for the German Wehrmacht. In September 1944, the family was deported to Auschwitz. Jerzy and his father were taken to the men’s camp, where Ernst Reichenbaum died in November 1944. Eduard and his mother were first brought to the women’s camp. However, like the mothers of Riwka Herszberg and Walter Jungleib, Sabina Reichenbaum was taken to the Lippstadt satellite camp in November 1944. Eduard was transferred to the children’s barracks, and moved to Neuengamme on 28 November 1944. He had turned ten two weeks previously. When Auschwitz was cleared, Jerzy was first taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, and then to Mauthausen. He survived, and succeeded in emigrating to Israel after liberation. His mother followed him there in 1947. In Israel, Jerzy renamed himself Ytzhak, and got married. He died in Haifa in 2020.

Marek Steinbaum (Szteinbaum, Sztajnbaum) was born in Radom on 26 May 1937. His parents were Mania, née Tauber, and Rachmiel Steinbaum. The family owned a small leather factory there. In March 1941, they were sent from the ghetto established by the German occupiers to the Pionki forced labour camp. From there, they were deported to Auschwitz, probably in early October 1944. From Auschwitz, his father was taken to the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Gross-Rosen, and to a satellite camp of the Natzweiler-Struthof camp near Stuttgart, where he survived the war. In November 1944, his mother was transported to the women’s satellite camp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, where the mothers of Marek James and of Eleonora and Roman Witoński were also incarcerated. She also survived. Marek was seven years old when he was taken to Neuengamme on 28 November 1944. After the end of the war, Rachmil and Mania Steinbaum lived in Memmingen. In 1947, they had a daughter. In 1949, the family emigrated to the US.

H. Wasserman, an eight-year-old girl from Poland, was probably born in 1937. Her surname, age, gender, and place of origin are only known from the list published by Dr. Henry Meyer in Copenhagen in 1945 in the book “Rapport fra Neuengamme”. The initials H.W. are also noted in a record by the camp doctor, Kurt Heißmeyer, who conducted medical experiments on the children.

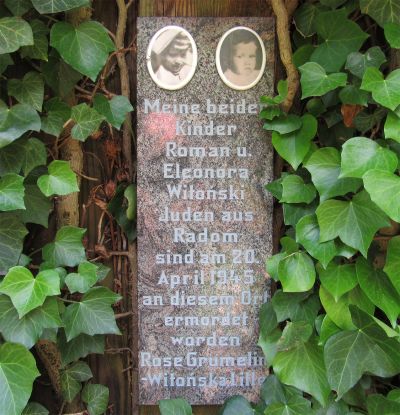

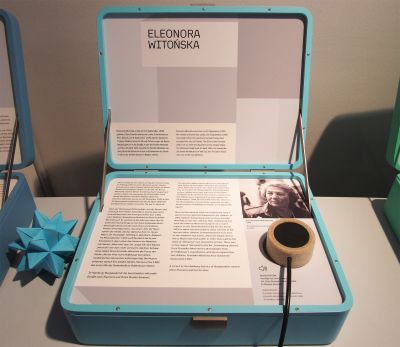

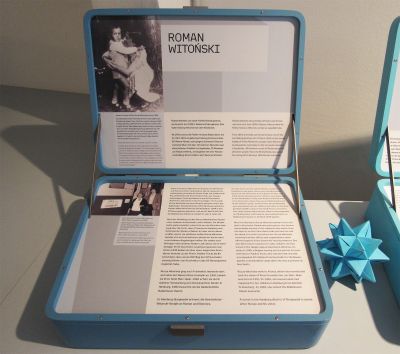

Eleonora and Roman Witoński came from Radom in Poland. Roman was born on 8 June 1938, Eleonora on 16 September 1939. Together with their mother Rucza and their father Seweryn Witoński, a paediatrician, they were forced to live in the ghetto established by the German occupiers in the spring of 1941. Over the course of several days on around 21 March 1943, the German police in Radom and the surrounding localities organised the “Purim campaign”, during which around 150 Jews were murdered. Over a hundred people who had previously reported to the ‘Jewish Council’ (Judenrat) requesting permission to travel abroad, including the Witoński family, were taken to the Jewish cemetery in Szydłowiec, twenty kilometres south-west of Radom. On the way there, they were joined by two lorries with volunteers, who began shooting them when they reached the cemetery.[5] Seweryn Witoński was among those who were murdered. After some time, the shooting stopped for reasons that are not known. Seweryn’s wife and two children were found hiding behind a gravestone and were returned to the ghetto together with the other survivors. In late July of 1944, they were taken to Pionki forced labour camp, and from there to Auschwitz. Rucza Witoński survived the war, emigrated to France, married, and had another son. Under her new name, Rose Grumelin, she searched for her children for over 30 years. Finally, in 1981, she discovered what had happened to them in Hamburg. She saw them for the last time in November 1944, in Auschwitz: she was separated from them and sent to the women’s camp, while they were taken to the children’s barracks. When Roman and Eleonora were deported to Neuengamme a short time later, they were six and five years old respectively. Rose Grumelin died in 2012 in Paris, aged 99.[6]

R. Zeller, a boy from Poland aged twelve, was probably born in 1933. His surname, age, gender, and place of origin are only known from the list published by Dr. Henry Meyer in Copenhagen in 1945 in the book “Rapport fra Neuengamme”. The camp doctor Kurt Heißmeyer also noted the initials R.Z. on one of his records, and used them to label one of the photos documenting his experiments with the children.

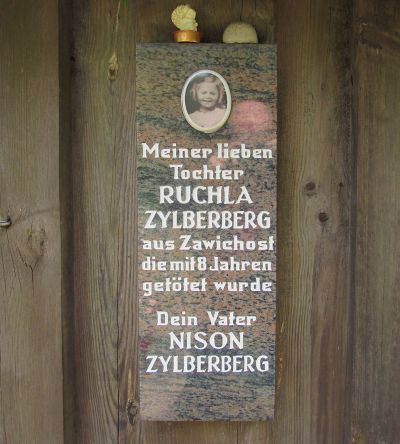

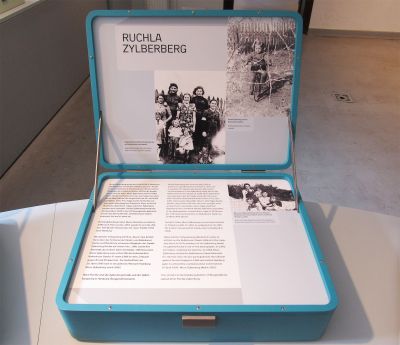

Ruchla Zylberberg was born on 6 May 1936. She was the daughter of Fajga, née Rosenblum, and Nison Zylberberg, a shoemaker, in the small Polish town of Zawichost, to the north of Sandomierz. Her sister Ester was born two years later. When the German Wehrmacht occupied Poland in 1939, her father fled to Russia with his brother and sister-in-law. He had originally planned to bring his family there at a later date, but this became impossible when the Germans attacked the Soviet Union. In 1942, the mother and daughters were taken to Auschwitz concentration camp, where Fajga and Ester were murdered. Ruchla was eight years old when she was taken to Neuengamme on 28 November 1944. Her father returned to Poland in 1946, and emigrated to the US in 1951. In 1979, his brother Henryk, who lived in Hamburg, was the first person to recognise Ruchla from a photograph in a press report about the children of Bullenhuser Damm. Nison Zylberberg confirmed the identity of his daughter. He died in 2002.

Human experiments on prisoners and children in the Neuengamme concentration camp

In the spring of 1944, leading medical experts from the German Reich government and members of the SS gathered for an informal meeting in the casino of the Heilanstalten Hohenlychen complex, which, from 1902 to 1945, was used as a clinic, in the town of Lychen in the Uckermark region of north Brandenburg. As well as housing the clinic itself, which originally specialised in the treatment of lung diseases, and more recently sports and occupational injuries, Hohenlychen also became a fashionable destination for prominent figures in the Nazi party, including Hitler and his ministers, as well as high-ranking members of the SS, generals and officers from the Waffen-SS, Reich officials, Reich sports leaders, state secretaries, and army officers. International delegations travelled there, too. The meeting in the spring of 1944 was attended by the Reich Health Leader Dr. Leonardo Conti, the Reich physicians’ leader for the SS and police, Dr. Ernst-Robert Grawitz, and the head physician at Hohenlychen, Prof. Dr. Karl Gebhardt, among others. At the meeting, a senior physician at the clinic, Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer, was invited to give a brief lecture.

Heißmeyer, who was born in Lamspringe in 1905, had earned his doctorate in Freiburg and had worked at Hohenlychen since 1938. His uncle, August Heißmeyer, was a Waffen-SS general. He was a friend of Oswald Pohl, a Waffen-SS general in the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt), who was responsible for the concentration camps. In order to gain his professorship, he was required to write a habilitation paper in which he aimed to tackle the treatment of tuberculosis. In his lecture, he suggested conducting a series of experiments on humans, in which patients suffering from tuberculosis were to be artificially infected with another tuberculosis pathogen. This was to be done by rubbing killed tuberculosis bacilli into a scratch on the skin, similar to administering a vaccine. This long-since debunked research approach originated from the Austrian doctor Hans Kutschera-Aichbergen, and was intended to improve immunity and healing in the lungs. Conti, Grawitz, and Gebhardt agreed that Heißmeyer should conduct the planned experiments on prisoners at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where Gebhardt had already experimented in various ways on prisoners, most of them women, since July 1942. However, approval was required from Reich Minister of the Interior Heinrich Himmler, who had reserved the right to issue permission for all human experiments, before the plan could go ahead. Finally, Pohl received Himmler’s consent, but only on condition that the tests were not conducted in Ravensbrück, since news had already reached the international community about Gebhardt’s experiments there. He and Heißmeyer decided that the Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg would be a somewhat “more discreet” place in which to conduct the trials.[7]

At the end of April 1944, Heißmeyer and Dr. Enno Lolling, formerly a camp doctor at Dachau and Sachsenhausen concentration camps and now head of the Office for Medical Services and Camp Hygiene (Amt für Sanitätswesen und Lagerhygiene) of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office, travelled to Neuengamme for the first time. The camp commander, Max Pauly, had arranged for a barracks to be specially prepared for Heißmeyer’s experiments. The windows were painted white and a wooden plank fence was erected to prevent anyone from being able to see what was happening inside. At Neuengamme, Heißmeyer was introduced to the camp doctor, Dr. Alfred Trzebinski, who was assigned the task of monitoring the experiments.

The trials began in June 1944, and were initially mainly conducted on Polish and Soviet prisoners. The test subjects were first chosen from three groups of sick prisoners: those with double-sided lung tuberculosis, those with just one infected lung, and those with tuberculosis in other organs. Next, healthy prisoners were infected with tuberculosis as a “control”. The highly infectious living tuberculosis bacilli used by Heißmeyer came from a bacteriological institute in Berlin which had no knowledge of the human experiments. Even the creation of the injection solutions in the barracks in Neuengamme took place under unprofessional and therefore life-threatening conditions. The prisoners were injected with living bacilli strains in the area of the heart muscle. After one week, lymph nodes were removed from their bodies and sent to Berlin and used to obtain new TB cultures. These cultures were again injected into the test subjects every 14 days. At the same time, their own infected saliva was rubbed into scratches on their skin. Tuberculosis serum was introduced into the lungs of the healthy subjects via a rubber tube.

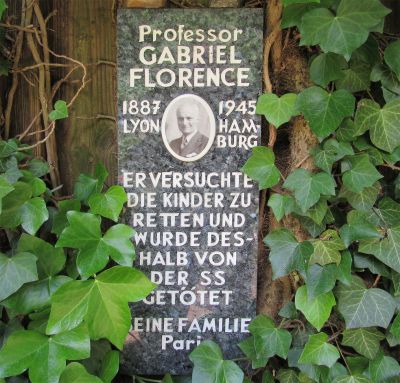

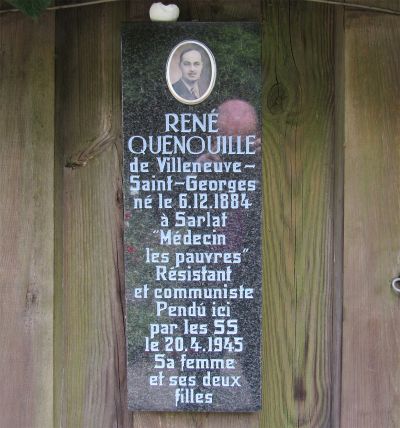

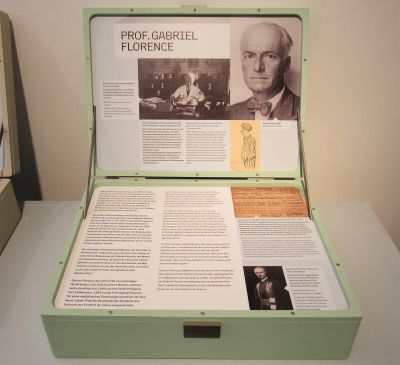

Initially, two imprisoned Polish doctors, Dr. Tadeusz Kowalski, who had previously been interned at Auschwitz, and Dr. Zygmunt Szafrański, were assigned the task of monitoring the progress of the test subjects. Both survived the war and were able to testify before the courts in 1946, Kowalski before the British military court in Hamburg during the main Neuengamme trial, and Szafrański before the examining magistrate in Radom, Kazimierz Borys.[8] Heißmeyer later replaced Kowalski and Szafrański with two imprisoned French doctors, Prof. Gabriel Florence and Dr. René Quenouille, who were hanged together with the children on 20 April 1945 in order to prevent them from testifying in the courts. It is not known how many adults were subjected to Heißmeyer’s pseudo-medical experiments. Overall, the figure is probably more than a hundred. The medical records of 32 test subjects have been preserved. At least 16 healthy prisoners were infected with tuberculosis.[9] They suffered from high fever, swelling of the lymph nodes, infections, and the formation of abscesses. After the experiments had been completed, several of the prisoners were executed and dissected, and the findings were analysed by Heißmeyer. Others died days or weeks afterwards. The survivors remained severely ill.[10]

On 22 March 1946, Dr. Tadeusz Kowalski gave the following statement in the main Neuengamme trial in Hamburg, also known as the Curiohaus Trial: “He [Heißmeyer] first came in the summer of 1944 and ordered the SDG [the SS medical service, SS-Sanitätsdienstgrad] to bring 50 sick prisoners from area II [...]. Of these 50, he selected 20 or 25 with single-lung TB. [...] They were Russians and Poles. […] Dr. Schrapansky [Szafrański] was interned with them for six days. He was strictly forbidden to go out. His food was brought by the SDG. He was required to record the state of the ill prisoners and to make clinical observations, while ensuring that cleanliness and order were maintained. [...] I have seen photographs with rubber tubes that were guided through the bronchi into the lungs. The photographs were taken by Prof. Heißmeyer. Quenouille was also present and said that he had injected either TB sputum or special TB into the healthy lung. [...] After a few weeks, Quenouille showed new X-ray images on which large, specific infiltrates could be seen. They also conducted inunctions on other sick prisoners, and a few weeks later, glands were removed from them. These patients later became extremely ill, and I know for a fact that by 18 April [1945], 50 % of them had died”.[11]

Heißmeyer, who initially managed to escape detection after the war, ran his own medical practice in the GDR until 1963 and was also the director of the private Klinik des Westens in Magdeburg. He was arrested in Magdeburg on 13 December 1963. In the preliminary hearings prior to the main trial, during which Dr. Szafrański also issued witness statements, Heißmeyer admitted that: “I knew that the serum was toxic, but I wanted to find out more about immunobiological behaviour in humans. I was aware that such experiments with a virulent serum were never permitted to be conducted on humans. However, on the other hand, I also knew that experiments on guinea pigs were of no use, since by nature, these animals do not contract tuberculosis. That is why I took my experiments to a concentration camp, where a sufficient number of test subjects were available, and where I was not required to take their welfare into account. I was aware of the risks arising from my experiments, and of their potentially lethal consequences, but I wanted to publish an academic paper. [...] To me, the prisoners at Neuengamme concentration camp, and the children brought there at my request in the autumn of 1944, were no more than test subjects...”[12]. After Heißmeyer realised in the autumn of 1944 that his attempts to cure tuberculosis among adults through artificial infection had failed, and that instead, the physical state of the prisoners had worsened, he “abandoned the experiments and requested that 20 children be brought, on which I conducted experiments related to immunisation against TB using the same serum, as well as to determine any already existing immunity”.[13]

In an interview transcript from 1956, the dentist Dr. Haja (Paulina) Trocki-Musnicki, who was born in Kishinev (today: Chișinău) in 1905, who studied in Belgium and who was deported from there to Auschwitz as a resistance fighter, reported on the transportation of the children from Auschwitz to Neuengamme on 28/29 November 1944. The interview was stenographed in Israel by the contemporary historian Kurt-Jacob Ball-Kaduri, originally from Berlin, for the Yad Vashem Remembrance Center: “From September or October 1944, when it [the war] was already nearing its end, children arriving at Auschwitz were no longer killed (or not all of them?). When I arrived in August, all of the children from my train were discarded. But afterwards, they remained alive, and at the end of the year, there were around 300 children in Auschwitz, in one block. [...] The children had it good, since all the adults somehow took care of them, i.e. all the prisoners. One day at midday, I was called to the camp leader, and was told that I would have to board a train with the children, to accompany them. Apart from me, there were three nurses, one of which was a laboratory assistant from Hungary. There were ten boys and ten girls, aged between six and twelve, all Jews, but from all kinds of different countries. Two of them were from Paris. I asked why the children were being sent away. I was told: all children without parents. I learned from the children that, in the labour camp, many of the parents had been sent away on trains”.[14]

The children, who were accompanied by the SS, were transported in a special train car, which was hitched to a normal passenger train. It travelled from Auschwitz right through Poland, and on to Neuengamme via Berlin. At 10 pm on 29 November 1944, it arrived at a side track at Neuengamme which led straight into the camp. During the journey, the children were “excellently” cared for, according to Trocki, and were given milk and chocolate. When they arrived, she witnessed someone beginning to cry when he saw the children. A Belgian medical student who worked in the pharmacy was afraid that the children would be used for experiments. However, there was a French doctor in the camp who tried to save the children. After that, though, she didn’t see the children again. They were taken to the barracks where the experiments were due to take place, and given bunk beds there. Dr. Trocki was later moved to the Helmstedt-Beendorf women’s satellite camp. The three nurses on the train, two of whom were Poles, according to a witness, “headed towards the bunker” with their few possessions.[15] Later, another witness in the main Neuengamme trial reported that four Polish women were executed in the bunker at Neuengamme[16]. However, nothing is known of their identity.

In the ante-room of the barracks, Prof. Florence, whose job it was to take blood and urine samples from the children, and Dr. Quenouille were housed. Dr. Quenouille was responsible for clinically monitoring them, for taking their temperatures, recording fever curves, and producing X-rays. They were assigned two “caretakers” from the Netherlands. These were the book printer Dirk Deutekom, born in Amsterdam in 1895, a resistance fighter who was arrested in July 1941 and who was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp about a year later, and the lorry driver and waiter Anton Hölzel from Den Haag, born in Deventer in 1909, who had been arrested in 1941 for the same reason and taken to Buchenwald in March 1942. Both Hölzel and Deutekom were hanged on Bullenhuser Damm on 20 April 1945 together with Florence, Quenouille, and the children.

Tuberculosis cultures were rubbed into the scratched skins of all the children, who developed a fever two to three days later. It is not known which children were infected with tuberculosis following the introduction of serum via a tube inserted into the lung. X-ray images found later, which were analysed after the war in the Charité hospital in Berlin, showed infiltrative changes to the pulmonary lobes of Jacqueline Morgenstern, Lelka Birnbaum and Sergio De Simone, which indicate such a procedure was carried out. Shortly before Christmas 1944, all the children were severely ill. Professors Florence and Quenouille and the caretakers Hölzel and Deutekom all developed a close and friendly relationship with the children. They made sure that they were well fed, and were even able to persuade the camp commander and the canteen cook to provide them with extra rations. Despite being strictly forbidden to do so, prisoners brought Christmas gifts that they had made and sewn themselves. The torture resumed from mid-January onwards. Since Heißmeyer was keen to determine whether antibodies against tuberculosis had developed in the lymph nodes, he requested that they be operatively removed by the incarcerated Czech medic Dr. Bogumil Doclik and then analysed in the laboratory at Hohenlychen. At the end, all the children were confined to bed and had become apathetic[17].

Detailed information about the operations became known through the Polish nurse Franciszek Czekała, whose assistance was required in the operating theatre. Czekała, who was born in 1911 in Gulcz in the Filehne district in the province of Posen (now Wieleń, Greater Poland Voivodeship), was evacuated from Neuengamme to Lübeck in April 1945, and from there was taken by train to Neustadt in Holstein, where Polish survivors were registered.[18] On 17 December 1945, Czekała, who had until then been housed in the neighbouring town of Haffkrug-Sierksdorf, gave the following report to the well-known Austrian-born examining officer of the British Rhine Army, agent of the British intelligence service (the SOE) and member of the War Crimes Investigation Team, Capt. Anton Walter Freud:

“On 14 June 1940, I was arrested by the Gestapo on suspicion of anti-German activity, came to Buchenwald and on 16 December 1940 was taken to Neuengamme, where I remained until 3 May 1945. Before 1 January 1942, I was part of a squad of prisoners that was made to work on the construction of the canal on the river Elbe. From 1 January 1942 onwards, I worked as a medical orderly in block 9, where typhus patients were kept. From 1943–45, I was a medical orderly in area I. In 1944, 20 children arrived at Neuengamme, aged between five and twelve. Most of them were Polish Jews; however, there were also two French children and several Dutch children. They were housed in area IV in an isolated room. The children were not allowed to leave this room, and the camp prisoners were not allowed in. [...] The people responsible for caring for these children, who were also isolated, were two Dutchmen and two French doctors, a radiologist and a professor. Six weeks after the children arrived, the area overseer Mai came to me – at that time, I worked in area I – and said that I should make preparatons for nine gland operations; a Czech doctor, Dr. Doslik (sic!), would conduct the operations; the operations would be conducted on the children from area IV. The bandaging room of area I was used as an operating theatre. I prepared clamps, tweezers, sharp hooks, scalpels, and Novocain. When everything was ready, at around 7 in the evening, the caretakers brought in the children one by one from area IV to area I. I was in the bandaging room of area I and was present during all operations. The children’s clothes were removed from their upper bodies, and the children were placed onto the operating table. Iodine was applied to the skin under their arms, and they were then injected with 10 cc of 2 % Novocain. Dr. Dozlik (sic!), the operating doctor, then felt the glands under the arm, made a 5 cm incision and removed the gland. He then sewed the wound together with silk. Each operation lasted around 15 minutes. Nine children were operated on that evening. The French caretakers put the glands in a vial with formalin spirit and labelled them with name and number. After the operation, the children were taken back to area IV. After seven days, the children were brought back to area I, and I removed the silk stitches. The glands of each child were removed below the arm in operations that took place approximately two weeks in succession. During the operations, I noticed that many of the children had cuts on their chests in a grid-like pattern, covering a square of 3–4 cm. I don’t know what that meant. [...] In mid-April 1945, the children were taken from Neuengamme. I don’t know what happened to them after that. The caretakers were also taken away.”[19]

The murder of the children, their caretakers, and the Soviet prisoners at Bullenhuser Damm

On 19 February 1945, Himmler, who was trying to secure a separate ceasefire with the western Allies, met the vice-president of the Swedish Red Cross, Count Folke Bernadotte, at Hohenlychen in order to negotiate the return of Scandinavian prisoners interned in German concentration camps. According to the agreement, the Scandinavians, most of whom came from Denmark and Norway, were to be brought together in Neuengamme and from there, taken northwards in what later became known as the “White Buses”. On 23 March, the British Second Army crossed the Rhine and advanced towards the north German lowlands. One day later, the clearing of the satellite camps of Neuengamme in the Emsland region began. By the end of the month, they were followed by the satellite camps in Hildesheim, Lengerich, Barkhausen, Lerberg, and Hausberge.[20] On 31 March, Count Bernadotte visited Neuengamme concentration camp, where he was received by the camp commander Pauly[21]. The Scandinavian prisoners were then transferred to Neuengamme from the concentration camps at Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, Dachau, Ravensbrück, Neubrandenburg, Zwickau, and Theresienstadt via the “White Buses”. On 4 April 1945, the British army units reached the Weser river.

From 14 to 17 April, the satellite camps of Neuengamme, Dessauer Ufer, Blohm & Voss, Spaldingstrasse and Bullenhuser Damm that were situated in Hamburg were cleared. The Bullenhuser Damm satellite camp in a former adult education centre which originally offered thirty classes (see title image) was converted into a concentration camp satellite by the SS in the autumn of 1944 after the Hamburg district of Rothenburgsort had been largely destroyed during a bombing raid on 27/28 July 1943 and the former school building had been damaged. The prisoners who arrived there in December 1944, who came from Poland, Denmark, France and the Soviet Union, were deployed to clear the area and to produce new stones from the rubble. According to the report by Trzebinski, at the end of March 1945, there were 592 prisoners in the camp. From 14 April onwards, the SS began to clear the Bullenhuser Damm satellite camp, where only Ewald Jauch and Johann Frahm from the SS remained. The prisoners were taken to the former Sandbostel prisoner-of-war camp near Bremervörde, which was now used as a collection camp.

On 19 April 1945, the British army units reached the Elbe river. On the same day, the commander Pauly ordered that the main camp at Neuengamme be cleared. All the Scandinavian prisoners were taken to Denmark on Red Cross buses. From 20 to 26 April, the remaining 900 prisoners were transported from Neuengamme to Lübeck. From there, they were sent to the former luxury steamship “Cap Arcona” and the freight ships “Thielbeck” and “Athen”. Given the fact that these ships were very likely to be torpedoed or bombed by the Allies, this amounted to sending the prisoners to their deaths. Around 7,000 were killed when the ships were bombed in the Bay of Lübeck by the Royal Air Force. A residual taskforce of 600–700 men remained at Neuengamme in order to clean up the camp, burn files, and remove the beating rack and gallows. The last prisoners and SS men departed shortly before British troops reached the camp on 2 May 1945.[22] During the seven years of the camp’s existence, at least 42,900 people died there and in the satellite camps. [23]

On the morning of 20 April, the protective custody camp leader (Schutzhaftlagerführer) and SS senior storm leader (Obersturmführer) Anton Thumann, who had previously served at the Dachau, Gross-Rosen, and Majdanek concentration camps, approached Trzebinski and said: “... I have something to tell you that is not exactly pleasant. Pauly wishes to let you know that an execution order has been issued by Berlin for the caretakers and the children, and that you are requested to kill the children using gas or poison”.[24] By this point in time, Heißmeyer had not visited Neuengamme for six weeks.[25] Trzebinski, who – if his later statement is to be believed – initially refused, was summoned that afternoon to Pauly, who confirmed that such an order had come from Berlin, and that it was Trzebinski’s duty to comply. During the Curiohaus trial, Pauly claimed on 2 April 1946 that the order had been issued to the doctor on site in the form of a telegraph or radio message. When challenged by the state prosecutor that such an order cannot have been addressed to a doctor, Pauly responded that: “In my opinion, this is not impossible, since the whole matter was a medical one. Trzebinski was always in the company of Professor Heißmeyer”.[26]

Just before 10 pm, two hours after the Danish buses had left the camp, the children and their caretakers were also taken away. During the Curiohaus trial, Trzebinski said in relation to this that: “I knew that the children and caretakers would be taken to Bullenhuser Damm; there was a phone call from the local headquarters. I don’t know who made the call, since it was accepted by the telephone service. The person on duty at the telephone service simply reported that they were to be taken to the camp, and that the car was ready. I therefore went to the camp, and saw the car waiting at the camp entrance. The car stopped; the engine was already running. I looked inside the car and saw the 20 children and four caretakers, as well as six other men. We got into the car: Dreimann, Wiehagen and Speck in the back, and me in the front. The car had already received clear marching orders. First, it drove to Spaldingstrasse. We arrived there an hour later. Dreimann, Wiehagen and, I got out of the car. Speck remained inside. Up above, Strippel appeared to be expecting us...”[27]

Wilhelm Dreimann and Heinrich Wiehagen were both SS junior squad leaders (Unterscharführer). Adolf Speck was the camp supervisor at Neuengamme. SS senior storm leader (Obersturmführer) Arnold Strippel, who had served in numerous concentration camps since 1935, was the base commander with responsibility for all the Hamburg satellite camps of Neuengamme. He was regarded as the second most powerful man after Pauly. In the Hamburg-Hammerbrook satellite camp in Spaldingstrasse 156–158, where Strippel was based, up to 2,000 prisoners from various countries, mainly Poland and the Soviet Union, were housed in the rear courtyard building of an office complex. After the bombing raids on Hamburg, they were sent to clear the rubble, recover bodies, and defuse bombs. According to Trzebinski’s statement when later interrogated, in the building in Spaldingstrasse, he took Strippel to one side and told him that he had intentionally not taken poison with him, since he could not bring it upon himself to kill the children. Finally, Strippel said: “If you’re too much of a coward to do it, then I’ll have to take the matter into my own hands”.

Trzebinski then claimed that: “He [Strippel] then drove ahead to Bullenhuser Damm in his car. We followed him and arrived there perhaps 10 minutes later. When we arrived and got out of the car, Strippel and Jauch and Frahm were just coming out of the door. Strippel went straight to his car, which was standing ready to leave, and said in passing that the matter was taken care of. I understood this to mean that he had made arrangements for the order from Berlin to be carried out. The passengers in the car then got out, the Russians, the caretakers and the children first. The Russians were taken to the room where the heating systems were. Then the carers and children were taken in. The caretakers went into a room opposite the children’s entrance. The children were taken to a room used as an air raid shelter. [...] I therefore stayed with the children, who were afraid. The children had all their belongings with them, including food, toys they had made themselves, etc. They left them lying on the benches and were in good spirits, and happy that they had finally got out of the camp. They had no idea what was about to happen. They were between five and twelve years of age. Half were boys, half girls. The children spoke in broken German with a Polish accent”. During this time, Jauch, Dreimann and Frahm hanged the doctors Florence and Quenouille in the adjacent room, together with the carers Hölzel and Deutekom and the six Soviet prisoners who had been brought there with them from Neuengamme.

Trzebinski continued: “After a while, Frahm came in and said that the children should undress. I saw that the children were rather reluctant to do so, and told them that they were being asked to undress so that they could be vaccinated against typhus. I then took Frahm out of the room so that the children couldn’t hear what we were saying, and asked him quietly what was going to happen to them. Frahm was also very pale, and said I should hang the children. [...] Now I knew what terrible end awaited the children. I wanted to at least make their final hours more comfortable. I had brought morphine with me, in a solution of 0.2 to 20.0. To be able to get the dosage right, I had diluted this bottle with 100 g of distilled water. This enabled me to give a better dose, taking into account the age of the children. I went to the door of the room, where there was a stool for the syringes, and next to it, another stool. I called each child individually, one after the other. They lay down over the stool and I gave them the injection into their backside, where it hurts the least. [...] The children started to feel tired and we lay them down on the ground and covered them with their clothes. Frahm left the room frequently, and I had the impression that he was also taking part in the execution of the men. I have to say with regard to the children that in general, they were in a very good physical condition, with the exception of a 12-year-old boy, who was very ill. As a result, this boy fell asleep very quickly. Frahm came back after 20 minutes. 6–8 of the children were still awake, but the others were already asleep. [...] Frahm took the 12-year-old under his arm and told the others that he was taking him to bed. He went with him into a room that was perhaps 6–8 metres away from the place where the children were being held, and there, I saw a noose on a hook. Frahm put the noose around the sleeping boy’s neck and pulled down with the full weight of his body onto the boy’s body, so that the noose was pulled tight. I have seen a great deal of human suffering during my time in the concentration camps, and had become desensitised to a certain extent, but I had never seen children being hanged. I felt sick, and I left the building and wandered around the block a few times”.

When Trzebinski returned half an hour later, the children were still in the process of being murdered: “Some of them were already gone. Others had not yet fallen asleep and asked me when they would be taken to bed. I went into the room where the first hanging had taken place and saw that a girl was hanging on another hook on the wall. In a partition next to the room lay the bodies of three children, including the body of the boy who had first been hanged. I did not see Frahm, and walked through the building. I heard voices next to the door of the room where the heating systems were. I went inside and saw Dreimann, Jauch, Wiehagen, and Frahm standing there. The bodies of four men were hanging in four nooses on a thick heating pipe. [...] I told Jauch that I was going to Spaldingstrasse, but that I’d come back soon. However, first of all, I went to the children and saw that some of them had still not properly fallen asleep. To make sure that they weren’t hanged while conscious, I gave them a second morphine injection. It was mainly among the bigger and stronger children for whom the morphine had not yet taken proper effect. As I said, I still had 20 cc in the bottle. I thought that this was not enough, and I took two more morphine vials from my doctor’s bag, each of which contained 0.015 cc. I added them to the rest, and injected doses that I thought would be sufficient. About 6 children were given extra doses. They reacted quickly, since they had already received a dose. I waited until all the children were fast asleep, and left for Spaldingstrasse”.

Pauly, Trzebinski, Frahm, and Jauch incriminated each other during the Curiohaus trial. Frahm, who was evidently the only one who admitted to hanging the children himself, gave the following deposition for the record on 24 May 1946: “There were about 20 children, aged between 12 and 16. Some of them appeared to be ill. Aside from the children, Dr. Trzebinski, Dreimann, and Jauch were also in the cellar. Strippel came in every so often. Wiehagen stood in front of the door, and Speck also stood guard in the building. The name of the driver who brought the children is Petersen. The children had to undress in a room in the cellar, and were then taken to another room, where they received an injection from Dr. Trzebinski which made them fall asleep. Those who still showed signs of life after the injection were carried into another room. A noose was placed around their necks and they were then hanged on hooks like pictures on the wall. The hangings were conducted by Jauch, myself, Trzebinski, and Dreimann. Strippel was also present at times. The bodies remained in the room, from where they were collected on the next day by people from Neuengamme”.

Frahm then described another murder that was carried out afterwards: “At around midnight, another draft of prisoners arrived from Neuengamme. This time, it was 20 adult Russian prisoners. They were taken to a room in the cellar, where they were hanged by the four of us: Jauch, Trzebinski, Dreimann and myself, and in some cases, Strippel. A rope was thrown around a pipe that ran below the ceiling. The noose was placed around the necks of the prisoners, and we hoisted them up. The bodies remained in the room, from where they were also collected the next day. By 6 in the morning, all the Russians were dead and I went to bed”.

However, Trzebinski testified that during that time, he had been at Spaldingstrasse working through patient records, before returning to Bullenhuser Damm: “I entered the building to see how the children were doing. There was no-one left in the room where the children had been. Only the baggage with their belongings had been left behind. I went into the room where the hangings had taken place and found it locked. [...] I then approached Frahm, who opened the room for me. The children were all lying there, and each child had the hanging mark on their neck. I then examined each child to make sure that it was dead. Then, I went into the room with the hanged men and also checked that they were dead. That was the end of this sorry chapter. We then drove back”.[28]

Although Pauly had ordered that the bodies be left at Bullenhuser Damm, Jauch later sent a car from Neuengamme, which Strippel brought back to Neuengamme with the corpses. The head of the crematorium in Neuengamme, SS junior squad leader (Unterscharführer) Wilhelm Brake, gave the following statement for the record on 14 May 1946 in Recklinghausen to a sergeant of the British Army of the Rhine: “I remember that about 14 days before the collapse [of the German Reich], a vehicle containing corpses arrived from Hamburg, probably from Bullenhuser Damm. There were around 40–50 bodies, and I was told by senior storm leader (Obersturmführer) Thumann that the bodies should not be cremated for the time being. I travelled by bicycle to the crematorium, where I discovered that work had already begun on the cremation of the bodies. I rode back and reported this to Thumann. Thumann then spoke to Dr. Trzebinski and it was decided that the bodies should be cremated after all. I then returned to the crematorium and told the prisoners that they could continue with their work. The prisoners then told me that among the bodies were the corpses of around 20 children”.[29]

The end of the war and the criminal prosecution of the perpetrators

When the first British soldiers entered the former concentration camp at Neuengamme on the evening of 2 May 1945, no evidence remained of the crimes that had been committed there. After the camp had been cleared, the camp commander Pauly had ordered around 400 kilogrammes of files to be burned by 2 May. The barracks were cleaned and lime washed, the gallows were sawn up and burned, and a sign was hung up in front of the crematorium with the word Desinfektionsraum ("room"). As the Neuengamme camp community (Lagergemeinschaft Neuengamme) later noted: “No-one was there”[30]. Directly on arrival, the British began to use the camp to house displaced persons and prisoners of war. Hamburg was now under British administrative control. On 1 May, Grand Admiral (Grossadmiral) Karl Dönitz, who became head of the German state after the suicide of Adolf Hitler, ordered the commander of Hamburg, Brigadier (Generalmajor) Alwin Wolz, to withdraw from the city without a fight. On 3 May, Wolz transferred the city to the command of the British brigadier-general Douglas Spurling.

At the same time, the headquarters of the British Army of the Rhine set up War Crimes Investigation Team (WCIT) No. 1, which was assigned the task of investigating the crimes that took place in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, which was liberated on 15 April. WCIT No. 2 began its investigations into Neuengamme concentration camp a short time later. The team included four officers, among them Capt. Anton Walter Freud, grandson of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who had emigrated to Britain in 1938. As early as May, a committee of former political prisoners from the Neuengamme camp made contact with the British Secret Service. At first, the report by the committee on the crimes committed in the camp was met with incredulity in the WCIT. The committee and the WCIT made a joint visit to the camp and discovered documents there, specifically the final quarterly report by the doctor on site and the register of the dead, which had been hidden by the prisoner Emil Zuleger. Only then did a relationship of trust develop between the two bodies, which led to collaboration in preparing for the trials of the perpetrators.[31]

On 6 May 1945, in a “Report for the Danish Red Cross”, the Danish doctor, Dr. Henry Meyer, who himself had been a prisoner at Neuengamme for a year-and-a-half, and who had been liberated following the rescue mission by the Swedish Red Cross, described the medical experiments conducted on prisoners and the tuberculosis tests on the children, and gave a list of the children’s names.[32] The Swedish doctor Gerhard Rundberg, who published the list together with Meyer in the book “Rapport fra Neuengamme” had led Count Folke Bernadotte’s rescue mission. Other survivors also gave reports about the children who had suddenly disappeared on 20 April. A systematic search then began for all those responsible for the crimes committed at Neuengamme. Among them were those who had ordered the murder of the children, those who had implemented this order, who had known of the murders, and who had been involved in them: camp commander Max Pauly, protective custody camp leader Anton Thumann, the medic Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer, the doctor on site Dr. Alfred Trzebinski, report leader Wilhelm Dreimann, SS junior squad leader Johann Frahm, SS senior squad leader and camp leader Ewald Jauch, junior squad leader Hans Friedrich Petersen, block and labour squad leader Adolf Speck, SS senior storm leader Arnold Strippel, and junior squad leader Heinrich Wiehagen.

After the camp had been cleared, Pauly had loaded 2,000 remaining care packages from the Swedish Red Cross onto a lorry and had driven to the apartment block where his parents-in-law lived, in Westerdeichstrich not far from Büsum in the district of Dithmarschen. There, Pauly and the former canteen manager Jacobsen who had accompanied him divided up the spoils of 400,000 cigarettes, 20,000 bars of chocolate and 20,000 packets of tea and coffee. After 3 May, Pauly hid in the house of his sister-in-law in Flensburg, the city to which the provisional Reich government headed by Dönitz had fled. Twelve days later, he was arrested there by civilian search agents working for the British Army, who took him to the internment camp in Neumünster. Frahm was arrested in his home town of Kleve in Dithmarschen, while Dreimann and Speck were arrested near Lübeck and also taken to Neumünster. Jauch was arrested in his home town of Schwenningen in the Black Forest and taken to the British internment camp at Eselsheide near Paderborn.

Trzebinski had also stolen Swedish Red Cross packages, loaded them onto an ambulance and driven to comrades in Husum with his booty. There, he removed the SS insignia from his uniform and from that time on, as he later wrote, “worked as the staff surgeon of the Wehrmacht in the reserve field hospital there”. Later, he had himself transferred to a field hospital in Hamburg, and from there obtained a post as a military doctor at the British discharge camp in Hesedorf near Neumünster. He arranged accommodation for his wife and daughter at a neighbouring inn. No-one asked for his papers – until finally, at the end of January 1946, Anton Walter Freud (who was later promoted to the rank of Major), a member of WCIT No. 2 in Bad Oeynhausen, tracked Trzebinski’s journey to Hesedorf, arrested him there, and had him taken to the internment camp at Westertimke to the north-east of Bremen.[33] Wiehagen had been deployed as an SS guard on the prisoner ship Cap Arcona. He is said to have shot at prisoners while the ship went down. One of the prisoners then beat him to death. Petersen, who had driven the lorry containing the children from Neuengamme to Bullenhuser Damm, was not targeted by the investigators and was also not questioned as a witness. After the war, he lived in Sonderburg in Denmark.

After the end of the war, Strippel went to ground at the home of a comrade from the SS in Büdelsdorf in Schleswig-Holstein, and then as an agricultural worker in Hesse. In December 1948, he was recognised on the street in the centre of Frankfurt/Main by a former prisoner of Buchenwald concentration camp, and was arrested shortly afterwards. In June 1949, he was sentenced in Frankfurt to lifelong imprisonment for his participation in the murder of 21 prisoners from Buchenwald concentration camp. In 1970, the verdict was annulled and the sentence shortened to six years for being an accessory to murder. Strippel received 121,500 Deutschmarks in compensation for the additional years that he had “unjustly” spent in prison. The other perpetrators of the murder had incriminated him in their statements during the Curiohaus trial, However, in June 1967, the state prosecutor in Hamburg dropped the case against him for his part in the murders at Bullenhuser Damm due to lack of evidence, since there was a possibility that they had hatched a conspiracy against him. In the legal appraisal of the case, the state prosecutor responsible, Helmut Münzberg, stated that: “The investigations have not shown with sufficient clarity that the children were made to suffer excessively before they died. On the contrary, there is some evidence that all the children, immediately on receiving the first injection, lost consciousness and for this reason were not aware of everything else that happened to them. Beyond the destruction of life, therefore, no further malady was inflicted upon them, in particular they were not made to suffer psychologically or physically for a particularly long time”.[34] After the relatives of the victims filed another criminal complaint, the state prosecution service in Hamburg resumed its investigations in 1979, and in 1983 charged Strippel with 42 counts of murder in relation to the children, the prisoner doctors and caretakers, and the Soviet prisoners. However, the proceedings were halted in 1987 as the accused was deemed unfit for trial. Strippel died in 1994 in Frankfurt/Main.[35]

Thumann, who had served at the Majdanek concentration camp in 1943/44, and who was known among inmates as the “butcher of Majdanek” for his involvement in the selection, gassing, and shooting of prisoners, had only known beforehand of the planned murder of the children. After the end of the war, he was recognised by former prisoners in the town of Rendsburg, and was arrested. During the first Curiohaus trial, he was accused of the murder of 13 women and 58 men, who had been brought from the police prison at Hamburg-Fuhlsbüttel to Neuengamme while the camp was being cleared.[36] No arrest warrant was issued for Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer for the human experiments that he carried out. After the war, he returned to his parents’ home in Sandersleben, to the north-east of Halle (Saale). There, he first worked in the medical practice run by his father, before setting up his own doctor’s surgery. He was arrested in Magdeburg in December 1963.

On 9 March 1946, Speck was the first to admit under oath to the British Captain H.P. Kinsleigh at the Neumünster camp that he had known of the transportation of the children from Neuengamme to Bullenhuser Damm. On the same day, Frahm admitted to Kinsleigh that the children had been murdered, although he passed on responsibility for their deaths to Trzebinski, who he claimed had killed the children by an “injection to the heart”.[37] On 18 March, the main Neuengamme trial (Neuengamme Camp Case No. 1) was opened at the Curiohaus in Rothenbaumchaussee in Hamburg. The building had formerly been used for social events and as a meeting place for the teachers’ association, and therefore had a large meeting hall. On trial were not only those responsible for the murders at Bullenhuser Damm, but also 14 members of the SS camp staff at Neuengamme, who were accused of killing and abusing citizens of Allied states. The interrogations under Freud were continued simultaneously. During the trial, the accused sat in a row, wearing signs showing a number. They included Pauly (1), Thumann (3), Dreimann (5), Speck (9) and Trzebinski (14). Their German lawyers sat in front of them, and British guards behind (Fig. 8 ).

Gradually, facts about what happened emerged through the interrogation protocols, the statements and confessions of the accused before the court, meaning false mutual accusations could no longer be upheld, and through witness statements. The general public in Hamburg quickly learned of the pseudo-medical experiments conducted at Neuengamme and the murders at Bullenhuser Damm via the local newspapers, including the “Hamburger Nachrichten-Blatt” published by the British military authority, the “Hamburger Freie Presse”, a liberal newspaper licensed by the British, the social democratic “Hamburger Echo” and the communist “Hamburger Volkszeitung”.[38] On 3 May 1946, all four of the accused, Pauly, Dreimann, Speck, and Trzebinski, were sentenced to death by hanging for the murders at Bullenhuser Damm. Seven other concentration camp murderers were also sentenced to death, including Thumann. On 31 May, Frahm and Jauch were charged in an ancillary trial, during which the men who had already been sentenced were required to make statements. They were also given the death penalty. All the death sentences were carried out between 8 and 11 October 1946.

In the years after the war, Heißmeyer opened a medical practice in Magdeburg, the only private practice for the treatment of tuberculosis in the GDR. He also became director of the small, also private, Klinik des Westens. In 1959, an editorial appeared in the West German magazine “Stern” in 1959, in which the author expressed his dismay that pupils in Federal German schools were not being told about Nazi crimes. The article also named Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer as an SS doctor in connection with tuberculosis experiments. After the article was published, an umbrella organisation of former prisoners of the Neuengamme concentration camp and the Committee of Anti-Fascist Resistance Fighters of the GDR (Komitee der antifaschistischen Widerstandskämpfer der DDR) began a search for more information. In December 1964, the office of the Attorney General of the GDR ordered the arrest of Heißmeyer. In an attempt to exonerate himself, Heißmeyer brought the investigators to a box that had been buried at Hohenlychen, the contents of which included X-ray images, fever charts and photographs of the children on whom operations had been conducted. He hoped that this information would prove that he had conducted his experiments according to strict scientific and ethical standards. However, an evaluation report by the Charité hospital in Berlin indicated the Heißmeyer had inserted tuberculosis bacteria directly into the lungs of at least three children. At a hearing on 6 April 1964, Heißmeyer finally confessed that “with these experiments on the children, [I have] committed a crime against humanity”. On 21 June, before the Magdeburg district court, a trial was opened against him for “crimes against humanity”. The trial ended on 30 June 1966, when he was sentence to life imprisonment. On 29 August 1967, 14 months later, Heißmeyer died in prison of a heart attack.[39]

The search for traces, documentation, remembrance. The erection of a memorial site

During the years that followed the Curiohaus trials, the memory of the murders at Bullenhuser Damm began to fade among the wider general public. In August 1948, the building was re-opened as a school. From the late 1950s onwards, former prisoners of the Neuengamme concentration camp regularly gathered at the school building to remember the events that took place there. In 1963, after many years of lobbying, the Hamburg Senate agreed to mount a memorial plaque dedicated to the murdered children and their four carers. No mention was made on the plaque of the Soviet prisoners who were executed there, however. In 1977, a journalist, Günther Schwarberg (1926–2008), drew attention to what had happened at Bullenhuser Damm. Schwarberg had first worked for the “Bremer Weserkurier” newspaper before moving on to “Radio Bremen” and a Düsseldorf-based agency for the Hamburg weekly magazine “Stern”.[40] After taking part in a memorial event in the cellar of the school, he began searching for traces of the murdered children. In Frankfurt/Main, in the archive of the Association of the Victims of the Nazi Regime (Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes), he discovered photographs of all 20 children, which had been taken for Heißmeyer by an SS photographer. He used these photos on search posters, which he had printed in Polish, Italian, Serbo-Croat and German, as well as in French, Dutch and English, and which he sent to different countries in the hope of finding the children’s relatives.[41]

The first person to contact Schwarberg was a civil servant at the state attorney’s office in Tel Aviv, who had recognised her cousin Riwka Herszberg from Zduńska Wola in Poland on one of the posters. According to Schwarberg,[42] one researcher found the Kohn and Morgenstern families in Paris. At a meeting in the Paris office of the attorney Serge Klarsfeld, the businessman Philippe Kohn recognised his brother Georges on one of the photographs. Dorothéa Morgenstern found her niece Jacqueline among the faces shown.[43] In the Netherlands, relatives were found of the murdered nurses Hölzel and Deutekom. From March 1979 onwards, Schwarberg published a six-part series in the “Stern” magazine entitled “The SS Doctor and the Children” (Der SS-Arzt und die Kinder), which described the full sequence of events from the deportation of the Kohn family in Paris in August 1944 through to the trial of Heißmeyer and the failed attempts to indict Strippel. In addition to conducting his own research, Schwarberg had access to the list published by Dr. Henry Meyer in Denmark, a brochure published in 1978 by the former prisoner at Neuengamme concentration camp, Fritz Bringmann, entitled “The Murder of the Children at Bullenhuser Damm” (Kindermord am Bullenhuser Damm), as well as the documents and results of the trial against Heißmeyer in the GDR. The series ended with a report of his latest contact with Michael Zylberberg, a 16-year-old living in Hamburg whose parents had recognised their niece Ruchla from Zawichost in Poland among the photographs published in “Stern”[44].

On 20 April 1979, over 2,000 people gathered for a memorial event to mark the 34th anniversary of the death of the victims of Bullenhuser Damm. Philippe Kohn and Dorothéa’s son, Henri Morgenstern, came from Paris, while the Zylberberg family from Hamburg also attended the event, as did the widow of Anton Hölzel, who travelled from the Netherlands. Together with former inmates of the Neuengamme concentration camp and members of the public living in Hamburg, they founded the Children of Bullenhuser Damm Association (Vereinigung Kinder vom Bullenhuser Damm e.V.) and submitted a formal request for a new criminal investigation against Strippel. In 1980, the association formally opened a memorial site in the cellar rooms of the school with a small exhibition. In a formal ceremony in April of the same year, the Hamburg Senate renamed the school the Janusz-Korczak School (Janusz-Korczak-Schule) (Fig. 37–39) in honour of the Polish doctor and educationalist Janusz Korczak, who in 1942 had voluntarily accompanied the Jewish children from an orphanage who were in his care to Treblinka concentration camp, and who went with them to his and their death.[45]

In 1979, Schwarberg published his first detailed book on the subject, “Der SS-Arzt und die Kinder”, at Gruner & Jahr in Hamburg. During the decades that followed, the book would be re-published numerous times, with varying titles. It was translated into French in 1981, into Romanian in 1982, into English in 1984 and into Japanese in 1991. In 1987, a Polish version was published entitled “Dzieciobójca. Eksperymenty lekarza SS w Neuengamme”. In 1996, the book was followed by Schwarberg’s diary, entitled “Meine zwanzig Kinder” (“My Twenty Children”; Steidl, Göttingen), detailing the story of the children and his search for information about them.

In 1979, as a result of the publication of the book, the aunt of Alexander and Eduard Hornemann, who lived in Eindhoven and who was the only member of the family to survive the war, found out about what had happened to her nephews. She remained in contact with the Association until her death in 2008, but refused to travel to Germany. In 1982, Rucza Witońska, who was by then married and known as Rose Grumelin, met Günther Schwarberg in Paris, and recognised her children Roman and Eleonora among the photographs he had brought with him. She travelled to Hamburg that same year. Since her death in 2012, her son Marc-Alain has regularly attended the memorial events. Also in 1982, the uncle of Mania, Chaim Altman, made contact with Schwarberg from the US, and came to Hamburg for the first time in 1986. In 1983, Gisella De Simone found out about the crime committed against her son Sergio. The following year, she attended the memorial event in Hamburg, although she refused to believe that her child had been murdered. Following her death in 1988, her younger son and his family attended the event in Hamburg every year on 20 April. In 1984, Ytzhak (Jerzy) Reichenbaum, who was living in Haifa, discovered the fate of his brother Eduard. From then on, he and his wife attended the memorial events at Bullenhuser Damm nearly every year, and also spoke to young people about what happened to their family.

In 1983, in collaboration with the Association, pupils created the rose garden, which still exists today and which was also designed by the Hamburg artist Lili Fischer. In 1985, the Soviet Ministry of Culture arranged for a bronze sculpture by the Russian artist Anatoli Mossitzschuk to be erected at the entrance to the garden in memory of the Soviet prisoners who were murdered (Fig. 9 , 10 ). At the gate of the rose garden, a granite panel was erected for each child and for each of the doctors and carers, showing a photograph fired in porcelain, together with information about their age and place of origin as well as a personal dedication (Fig. 11–34 ).

In 1986, in order to document the failure of the German judiciary to deal appropriately with Arnold Strippel, the Association organised an international tribunal at the Bullenhuser Damm memorial site (Gedenkstätte Bullenhuser Damm). The multi-day event was attended by lawyers from the countries of origin of the victims and was chaired by the former German constitutional judge, Martin Hirsch. The aim of the event was to clarify why Strippel, one of the main suspects in the murder of the children, had not appeared before a court and why the Federal German judiciary in general prevented or delayed the pursuit of Nazi criminals. Excerpts from the protocols from the Curiohaus trials were read out, and statements were heard from relatives, witnesses, and experts. According to Schwarberg: “When Niso Zylberberg, the father of Ruchla, came forward, the thousand people present stood up in silence. He was unable to speak through his tears. Jizhak Reichenbaurn gave a description of his brother Eduard, while Margarete Wilkens spoke of Sergio De Simone and Chaim Altman of his small niece Mania. On 20 April 1986, the judges came to the following conclusion: ‘The failure to prosecute the criminals involved in the murders at Bullenhuser Damm is not an isolated case, but is exemplary of the manner in which the Federal German judiciary handles Nazi crimes. A state which fails to punish the crimes of the Nazi regime is vulnerable to new fascism’”.[46]

In 1987, in the stairwell of the memorial site, a wall painting was installed by Hamburg artist Jürgen Waller entitled “21 April 1945, 5 o’clock in the morning” (21 April 1945, 5 Uhr morgens). The painting depicts what the artist imagined the morning after the crime must have looked like (Fig. 35 ). In 1992, streets, a park, and a playhouse in the Burgwedel new residential area of Hamburg-Schnelsen were named after the children. In 1994, in collaboration with the Neuengamme concentration camp memorial site (KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme), the site at Bullenhuser Damm was given a new permanent exhibition. In 1999, it was established as a branch of the Neuengamme site, and thus came under control of the Hamburg municipality as part of the city’s cultural authority. Today, the memorial site is part of the Foundation of Hamburg Memorials and Learning Centres Commemorating the Victims of Nazi Crimes (Stiftung Hamburger Gedenkstätten und Lernorte zur Erinnerung an die Opfer der NS-Verbrechen). In 2000, a memorial stele by the Russian artist Leonid Mogilevski, with portraits cast in bronze and the names of the 20 children, was erected on Roman-Zeller-Platz in Burgwedel, which was named after the Polish boy R. Zeller (Fig. 36 ). In 2011, the Bullenhuser Damm memorial site was expanded and the exhibition was redesigned.

It was not until 1993 that Lola Steinbaum, who had been born two years after the war and who had emigrated to the US with her parents, discovered what had happened to her brother Marek from Radom. In 1999, she came to Hamburg to attend the memorial ceremony on 20 April. In 1998, Shifra Mor, the sister of Bluma Mekler, who was born in Sandomierz and who now lived in Tel Aviv, visited the memorial site for the first time, and also travelled to the Bluma Mekler nursery run by the German Red Cross (DRK-Kindertagesstätte Bluma Mekler) in Burgwedel. From 2012 onwards, other family members travelled from Israel and London to attend the ceremonies in Hamburg. In 2010, a cousin and a great cousin of Marek James, who also came from Radom, got in touch. They were living in Israel and Toronto respectively. In 2011, they met Marek’s brother Mark, who was born after the war, at the ceremony in Hamburg on 20 April. Amalia Klygerman, who was born in Israel, found out about the fate of her sister Lea through the family of another victim, but kept the information to herself to protect her mother, who was still alive. Greta Hamburg, née Jungleib, who lived in Tel Aviv, only found out what happened to her brother Walter in 2015, having assumed until then that he had died on a death march from the concentration camp at Auschwitz. The Reichenbaum family had discovered the name “Jungleib” on a transport list to the Lippstadt satellite camp, made the connection to Walter, and contacted the family via the Yad Vashem memorial site. In 2016, Greta Hamburg attended the memorial ceremony in Hamburg for the first time.[47]

The Bullenhuser Damm memorial site, together with the rooms in which the murders were committed, is located in the basement of the former Janusz-Korczak school on Bullenhuser Damm 92 in Hamburg-Rothenburgsort (Fig. 37–39 ). After the large-scale bombing raids of the Second World War, the school building stands alone in an area of the edge of the port used by transport companies. After the war, the area was left to fend for itself. In the centre of the first room in the exhibition there are symbolic suitcases containing biographical information and photos of the children and their families. There are also suitcases showing information about the doctors and caretakers who were murdered together with the children (Fig. 40–47 ). Display panels provide information about persecution and deportation, the medical experiments, the Bullenhuser Damm satellite concentration camp, the murders, the perpetrators, and the Soviet prisoners. The second room contains cabinets with files and loose-leaf binders with more in-depth materials, as well as copies of documents and photographs for general use (Fig. 48 . ). Visitors then pass through a third room showing quotes by the perpetrators taken from the investigation protocols, and on into the room where the murders were committed, which is largely empty (Fig. 49 ). Since the opening of the memorial site, another of the rooms used as a bomb shelter during the Second World War serves as a place of silent remembrance (Fig. 50 ).