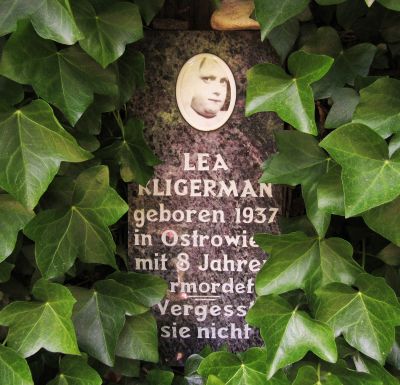

The children of Bullenhuser Damm

Mediathek Sorted

Thumann, who had served at the Majdanek concentration camp in 1943/44, and who was known among inmates as the “butcher of Majdanek” for his involvement in the selection, gassing, and shooting of prisoners, had only known beforehand of the planned murder of the children. After the end of the war, he was recognised by former prisoners in the town of Rendsburg, and was arrested. During the first Curiohaus trial, he was accused of the murder of 13 women and 58 men, who had been brought from the police prison at Hamburg-Fuhlsbüttel to Neuengamme while the camp was being cleared.[36] No arrest warrant was issued for Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer for the human experiments that he carried out. After the war, he returned to his parents’ home in Sandersleben, to the north-east of Halle (Saale). There, he first worked in the medical practice run by his father, before setting up his own doctor’s surgery. He was arrested in Magdeburg in December 1963.

On 9 March 1946, Speck was the first to admit under oath to the British Captain H.P. Kinsleigh at the Neumünster camp that he had known of the transportation of the children from Neuengamme to Bullenhuser Damm. On the same day, Frahm admitted to Kinsleigh that the children had been murdered, although he passed on responsibility for their deaths to Trzebinski, who he claimed had killed the children by an “injection to the heart”.[37] On 18 March, the main Neuengamme trial (Neuengamme Camp Case No. 1) was opened at the Curiohaus in Rothenbaumchaussee in Hamburg. The building had formerly been used for social events and as a meeting place for the teachers’ association, and therefore had a large meeting hall. On trial were not only those responsible for the murders at Bullenhuser Damm, but also 14 members of the SS camp staff at Neuengamme, who were accused of killing and abusing citizens of Allied states. The interrogations under Freud were continued simultaneously. During the trial, the accused sat in a row, wearing signs showing a number. They included Pauly (1), Thumann (3), Dreimann (5), Speck (9) and Trzebinski (14). Their German lawyers sat in front of them, and British guards behind (Fig. 8 ).

Gradually, facts about what happened emerged through the interrogation protocols, the statements and confessions of the accused before the court, meaning false mutual accusations could no longer be upheld, and through witness statements. The general public in Hamburg quickly learned of the pseudo-medical experiments conducted at Neuengamme and the murders at Bullenhuser Damm via the local newspapers, including the “Hamburger Nachrichten-Blatt” published by the British military authority, the “Hamburger Freie Presse”, a liberal newspaper licensed by the British, the social democratic “Hamburger Echo” and the communist “Hamburger Volkszeitung”.[38] On 3 May 1946, all four of the accused, Pauly, Dreimann, Speck, and Trzebinski, were sentenced to death by hanging for the murders at Bullenhuser Damm. Seven other concentration camp murderers were also sentenced to death, including Thumann. On 31 May, Frahm and Jauch were charged in an ancillary trial, during which the men who had already been sentenced were required to make statements. They were also given the death penalty. All the death sentences were carried out between 8 and 11 October 1946.

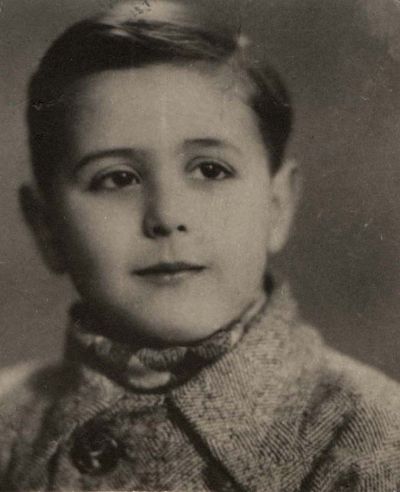

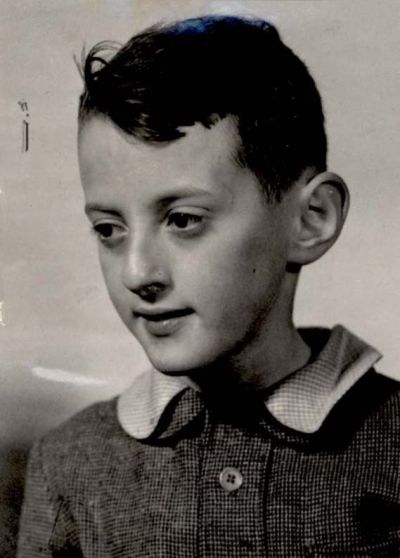

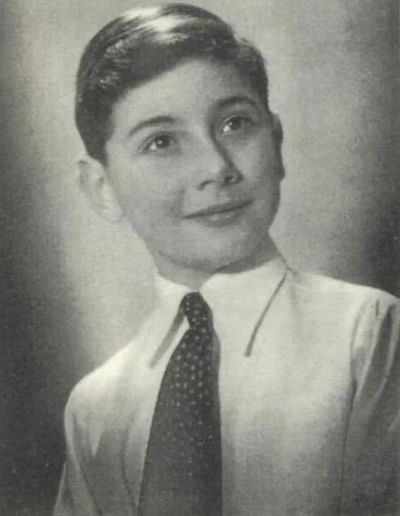

In the years after the war, Heißmeyer opened a medical practice in Magdeburg, the only private practice for the treatment of tuberculosis in the GDR. He also became director of the small, also private, Klinik des Westens. In 1959, an editorial appeared in the West German magazine “Stern” in 1959, in which the author expressed his dismay that pupils in Federal German schools were not being told about Nazi crimes. The article also named Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer as an SS doctor in connection with tuberculosis experiments. After the article was published, an umbrella organisation of former prisoners of the Neuengamme concentration camp and the Committee of Anti-Fascist Resistance Fighters of the GDR (Komitee der antifaschistischen Widerstandskämpfer der DDR) began a search for more information. In December 1964, the office of the Attorney General of the GDR ordered the arrest of Heißmeyer. In an attempt to exonerate himself, Heißmeyer brought the investigators to a box that had been buried at Hohenlychen, the contents of which included X-ray images, fever charts and photographs of the children on whom operations had been conducted. He hoped that this information would prove that he had conducted his experiments according to strict scientific and ethical standards. However, an evaluation report by the Charité hospital in Berlin indicated the Heißmeyer had inserted tuberculosis bacteria directly into the lungs of at least three children. At a hearing on 6 April 1964, Heißmeyer finally confessed that “with these experiments on the children, [I have] committed a crime against humanity”. On 21 June, before the Magdeburg district court, a trial was opened against him for “crimes against humanity”. The trial ended on 30 June 1966, when he was sentence to life imprisonment. On 29 August 1967, 14 months later, Heißmeyer died in prison of a heart attack.[39]

[36] See also the file on Anton Thumann from the KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme at: http://media.offenes-archiv.de/ss2_1_4_bio_1969.pdf

[37] Quotes from the interrogation protocols in Schwarberg: SS-Arzt 1997 (see Bibliography), page 79–81

[38] Newspaper cuttings reproduced in: Dossier Täter vor Gericht: Die Curio-Haus-Prozesse. Presseberichte, at: http://media.offenes-archiv.de/01_gruen_presseberichte_01.04.11_klein.pdf

[39] For detailed information on Heißmeyer, see Schwarberg: SS-Arzt 1997 (see Bibliography), page 92–110; the quote on page 98 is from the court files of the office of the Attorney General of the GDR.