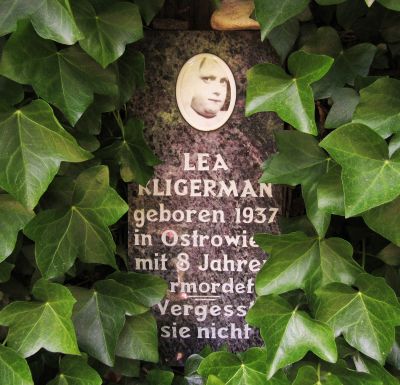

The children of Bullenhuser Damm

Mediathek Sorted

Just before 10 pm, two hours after the Danish buses had left the camp, the children and their caretakers were also taken away. During the Curiohaus trial, Trzebinski said in relation to this that: “I knew that the children and caretakers would be taken to Bullenhuser Damm; there was a phone call from the local headquarters. I don’t know who made the call, since it was accepted by the telephone service. The person on duty at the telephone service simply reported that they were to be taken to the camp, and that the car was ready. I therefore went to the camp, and saw the car waiting at the camp entrance. The car stopped; the engine was already running. I looked inside the car and saw the 20 children and four caretakers, as well as six other men. We got into the car: Dreimann, Wiehagen and Speck in the back, and me in the front. The car had already received clear marching orders. First, it drove to Spaldingstrasse. We arrived there an hour later. Dreimann, Wiehagen and, I got out of the car. Speck remained inside. Up above, Strippel appeared to be expecting us...”[27]

Wilhelm Dreimann and Heinrich Wiehagen were both SS junior squad leaders (Unterscharführer). Adolf Speck was the camp supervisor at Neuengamme. SS senior storm leader (Obersturmführer) Arnold Strippel, who had served in numerous concentration camps since 1935, was the base commander with responsibility for all the Hamburg satellite camps of Neuengamme. He was regarded as the second most powerful man after Pauly. In the Hamburg-Hammerbrook satellite camp in Spaldingstrasse 156–158, where Strippel was based, up to 2,000 prisoners from various countries, mainly Poland and the Soviet Union, were housed in the rear courtyard building of an office complex. After the bombing raids on Hamburg, they were sent to clear the rubble, recover bodies, and defuse bombs. According to Trzebinski’s statement when later interrogated, in the building in Spaldingstrasse, he took Strippel to one side and told him that he had intentionally not taken poison with him, since he could not bring it upon himself to kill the children. Finally, Strippel said: “If you’re too much of a coward to do it, then I’ll have to take the matter into my own hands”.

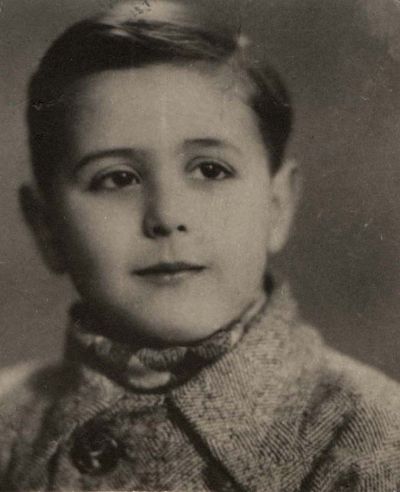

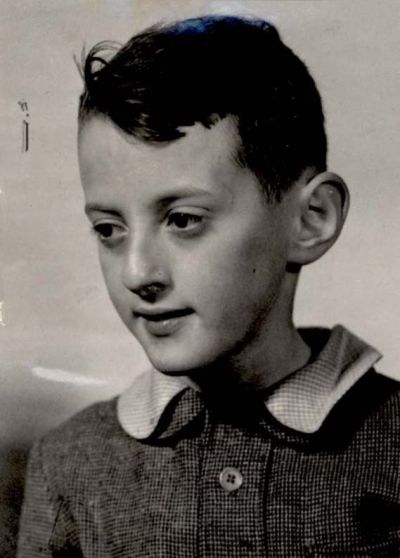

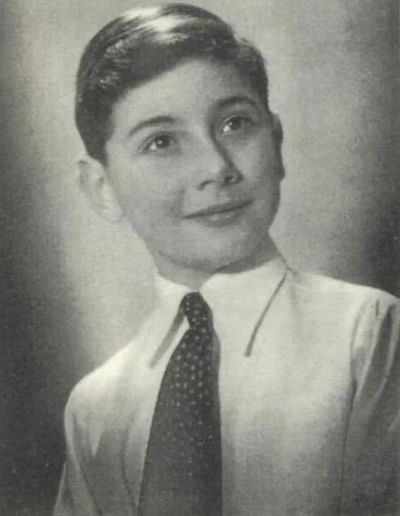

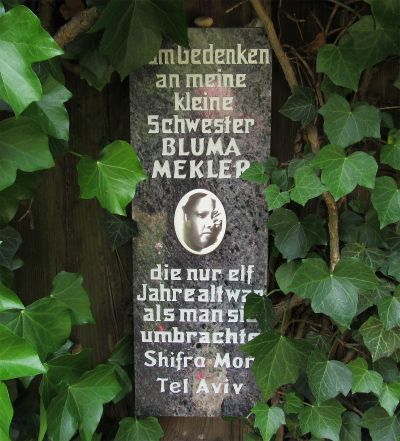

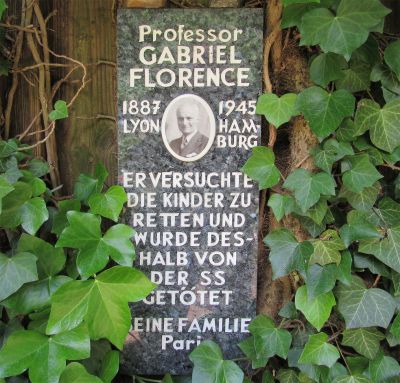

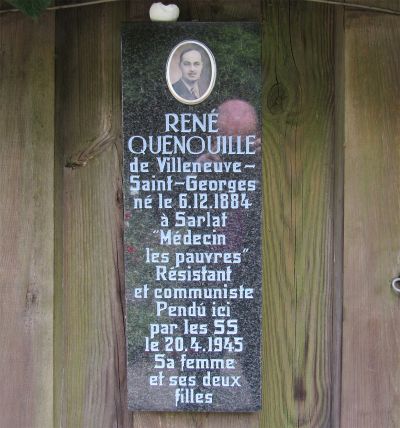

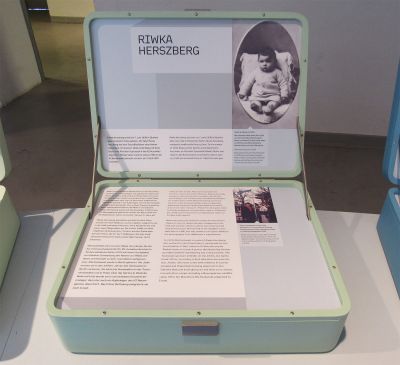

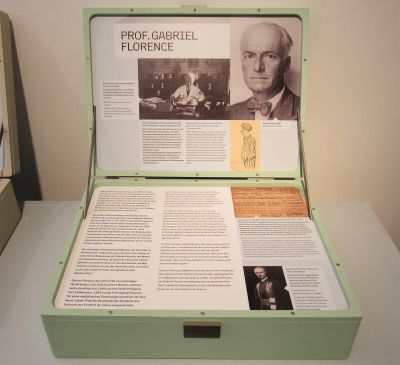

Trzebinski then claimed that: “He [Strippel] then drove ahead to Bullenhuser Damm in his car. We followed him and arrived there perhaps 10 minutes later. When we arrived and got out of the car, Strippel and Jauch and Frahm were just coming out of the door. Strippel went straight to his car, which was standing ready to leave, and said in passing that the matter was taken care of. I understood this to mean that he had made arrangements for the order from Berlin to be carried out. The passengers in the car then got out, the Russians, the caretakers and the children first. The Russians were taken to the room where the heating systems were. Then the carers and children were taken in. The caretakers went into a room opposite the children’s entrance. The children were taken to a room used as an air raid shelter. [...] I therefore stayed with the children, who were afraid. The children had all their belongings with them, including food, toys they had made themselves, etc. They left them lying on the benches and were in good spirits, and happy that they had finally got out of the camp. They had no idea what was about to happen. They were between five and twelve years of age. Half were boys, half girls. The children spoke in broken German with a Polish accent”. During this time, Jauch, Dreimann and Frahm hanged the doctors Florence and Quenouille in the adjacent room, together with the carers Hölzel and Deutekom and the six Soviet prisoners who had been brought there with them from Neuengamme.

Trzebinski continued: “After a while, Frahm came in and said that the children should undress. I saw that the children were rather reluctant to do so, and told them that they were being asked to undress so that they could be vaccinated against typhus. I then took Frahm out of the room so that the children couldn’t hear what we were saying, and asked him quietly what was going to happen to them. Frahm was also very pale, and said I should hang the children. [...] Now I knew what terrible end awaited the children. I wanted to at least make their final hours more comfortable. I had brought morphine with me, in a solution of 0.2 to 20.0. To be able to get the dosage right, I had diluted this bottle with 100 g of distilled water. This enabled me to give a better dose, taking into account the age of the children. I went to the door of the room, where there was a stool for the syringes, and next to it, another stool. I called each child individually, one after the other. They lay down over the stool and I gave them the injection into their backside, where it hurts the least. [...] The children started to feel tired and we lay them down on the ground and covered them with their clothes. Frahm left the room frequently, and I had the impression that he was also taking part in the execution of the men. I have to say with regard to the children that in general, they were in a very good physical condition, with the exception of a 12-year-old boy, who was very ill. As a result, this boy fell asleep very quickly. Frahm came back after 20 minutes. 6–8 of the children were still awake, but the others were already asleep. [...] Frahm took the 12-year-old under his arm and told the others that he was taking him to bed. He went with him into a room that was perhaps 6–8 metres away from the place where the children were being held, and there, I saw a noose on a hook. Frahm put the noose around the sleeping boy’s neck and pulled down with the full weight of his body onto the boy’s body, so that the noose was pulled tight. I have seen a great deal of human suffering during my time in the concentration camps, and had become desensitised to a certain extent, but I had never seen children being hanged. I felt sick, and I left the building and wandered around the block a few times”.

[27] Dr. Alfred Trzebinski's statement on 2/4/1946, Curiohaus Trial 1969 (see Bibliography), Volume I, page 346–351, quoted from: Dossier Täter vor Gericht (see footnote 1; also in Schwarberg: SS-Arzt 1997 (see Bibliography), page 56