The children of Bullenhuser Damm

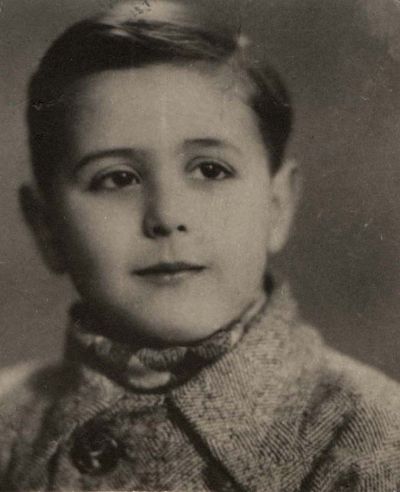

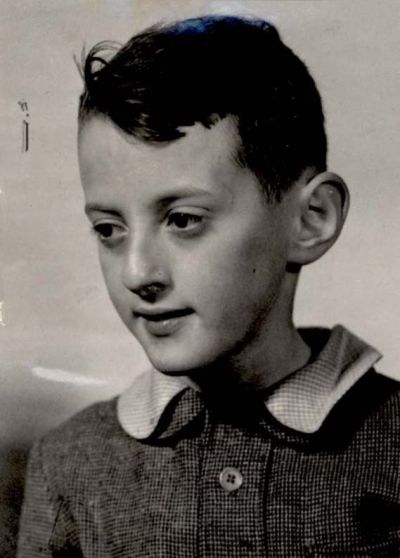

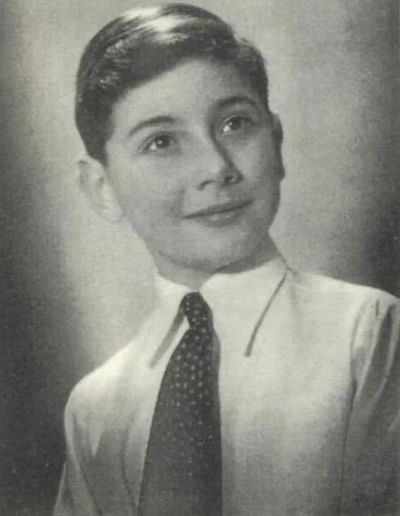

Mediathek Sorted

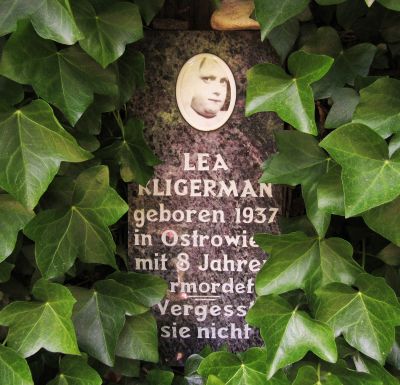

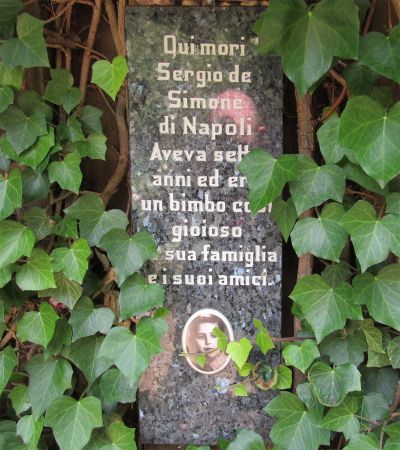

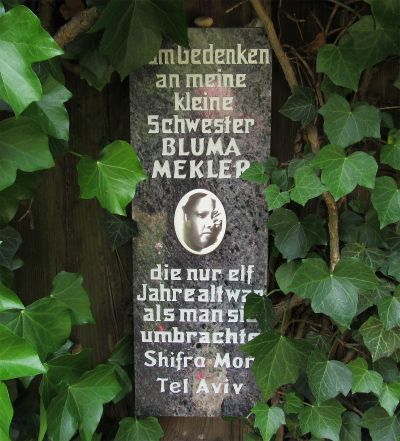

It was not until 1993 that Lola Steinbaum, who had been born two years after the war and who had emigrated to the US with her parents, discovered what had happened to her brother Marek from Radom. In 1999, she came to Hamburg to attend the memorial ceremony on 20 April. In 1998, Shifra Mor, the sister of Bluma Mekler, who was born in Sandomierz and who now lived in Tel Aviv, visited the memorial site for the first time, and also travelled to the Bluma Mekler nursery run by the German Red Cross (DRK-Kindertagesstätte Bluma Mekler) in Burgwedel. From 2012 onwards, other family members travelled from Israel and London to attend the ceremonies in Hamburg. In 2010, a cousin and a great cousin of Marek James, who also came from Radom, got in touch. They were living in Israel and Toronto respectively. In 2011, they met Marek’s brother Mark, who was born after the war, at the ceremony in Hamburg on 20 April. Amalia Klygerman, who was born in Israel, found out about the fate of her sister Lea through the family of another victim, but kept the information to herself to protect her mother, who was still alive. Greta Hamburg, née Jungleib, who lived in Tel Aviv, only found out what happened to her brother Walter in 2015, having assumed until then that he had died on a death march from the concentration camp at Auschwitz. The Reichenbaum family had discovered the name “Jungleib” on a transport list to the Lippstadt satellite camp, made the connection to Walter, and contacted the family via the Yad Vashem memorial site. In 2016, Greta Hamburg attended the memorial ceremony in Hamburg for the first time.[47]

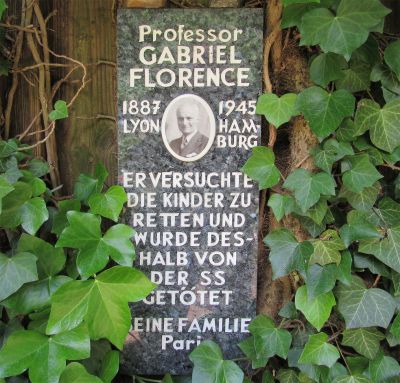

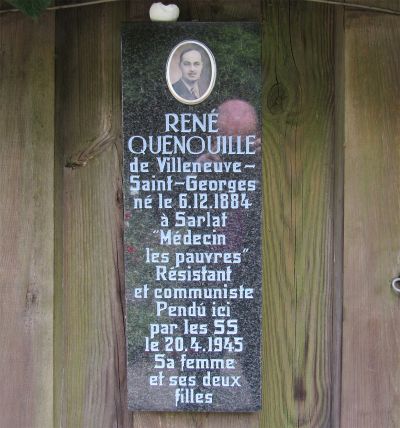

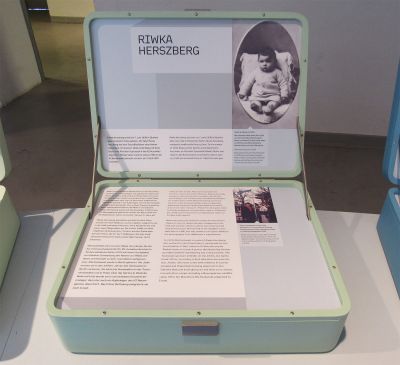

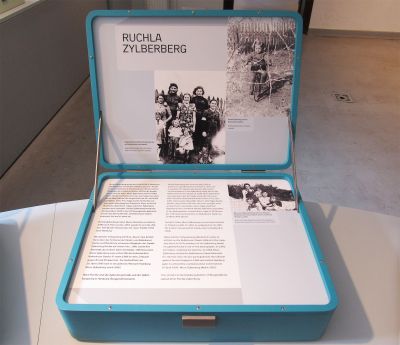

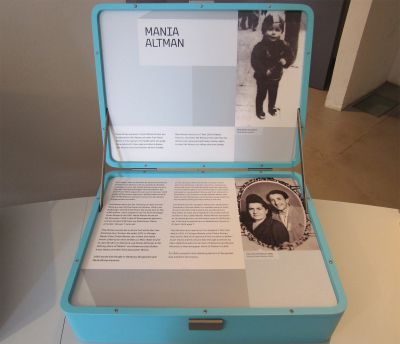

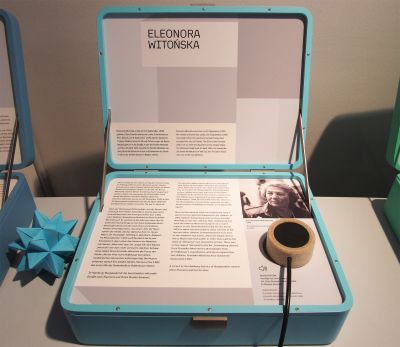

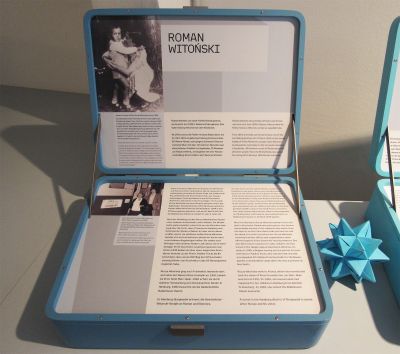

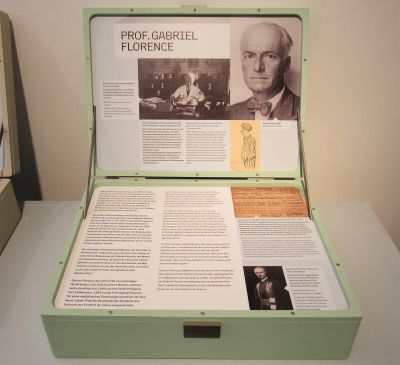

The Bullenhuser Damm memorial site, together with the rooms in which the murders were committed, is located in the basement of the former Janusz-Korczak school on Bullenhuser Damm 92 in Hamburg-Rothenburgsort (Fig. 37–39 ). After the large-scale bombing raids of the Second World War, the school building stands alone in an area of the edge of the port used by transport companies. After the war, the area was left to fend for itself. In the centre of the first room in the exhibition there are symbolic suitcases containing biographical information and photos of the children and their families. There are also suitcases showing information about the doctors and caretakers who were murdered together with the children (Fig. 40–47 ). Display panels provide information about persecution and deportation, the medical experiments, the Bullenhuser Damm satellite concentration camp, the murders, the perpetrators, and the Soviet prisoners. The second room contains cabinets with files and loose-leaf binders with more in-depth materials, as well as copies of documents and photographs for general use (Fig. 48 . ). Visitors then pass through a third room showing quotes by the perpetrators taken from the investigation protocols, and on into the room where the murders were committed, which is largely empty (Fig. 49 ). Since the opening of the memorial site, another of the rooms used as a bomb shelter during the Second World War serves as a place of silent remembrance (Fig. 50 ).

In 2019, the cultural scientist Natalia Budzyńska, who lives and works in Poznań, published a nearly 400 page-long book, “Dzieci nie płakały” (“The Children Didn’t Cry”) about her “uncle Alfred Trzebinski, an SS doctor” (Historia mojego wuja Alfreda Trzebinskiego, lekarza SS), after having come across the family secret that had been kept hidden for decades. Herself a Trzebińska by birth, she had discovered that Alfred was a son of her great-great uncle; in other words, he was her cousin three times removed. The family was descended from an impoverished noble family from Greater Poland. Alfred’s father, Stefan Trzebiński, who worked as a grammar school teacher in Jutroschin/Jutrosin, had married the German Maria Lepke and brought up his children as Germans. Alfred Trzebinski, who used a German spelling of his name, studied medicine in Breslau and Greifswald, where he gained his doctorate in 1928, and married a fellow student from Germany. In 1932, he joined the SS, became a member of the NSDAP a year later, and in June 1943 was promoted to the rank of SS Hauptsturmführer. From information she found in the Polish and German archives and in Trzebinski’s diary, which had been preserved, Budzyńska was able to reconstruct the life story and the crimes of her relative.[48]

Axel Feuß, June 2022

The author wishes to thank Dr. Iris Groschek from the Foundation of Hamburg Memorials and Learning Centres Commemorating the Victims of Nazi Crimes (Stiftung Hamburger Gedenkstätten und Lernorte zur Erinnerung an die Opfer der NS-Verbrechen), for her critical appraisal of this text and for providing further information.

[47] Kristina Festring-Hashem Zadeh: Von SS ermordetes Kind hat jetzt ein Gesicht, at ndr.de (22/9/2015), https://www.ndr.de/geschichte/Von-SS-ermordetes-Kind-hat-jetzt-ein-Gesicht,bullenhuserdamm138.html

[48] For more detail, see also the review by the sociologist Lech M. Nijakowski (see Online), Professor for Sociology at the University of Warsaw. Natalia Budzyńska’s book provides the basis for the entry on Alfred Trezbinski in the Polish Wikipedia