The children of Bullenhuser Damm

Mediathek Sorted

In 1979, Schwarberg published his first detailed book on the subject, “Der SS-Arzt und die Kinder”, at Gruner & Jahr in Hamburg. During the decades that followed, the book would be re-published numerous times, with varying titles. It was translated into French in 1981, into Romanian in 1982, into English in 1984 and into Japanese in 1991. In 1987, a Polish version was published entitled “Dzieciobójca. Eksperymenty lekarza SS w Neuengamme”. In 1996, the book was followed by Schwarberg’s diary, entitled “Meine zwanzig Kinder” (“My Twenty Children”; Steidl, Göttingen), detailing the story of the children and his search for information about them.

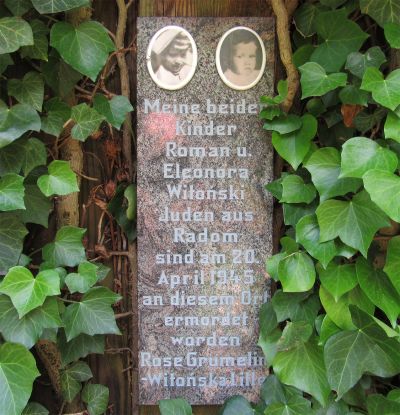

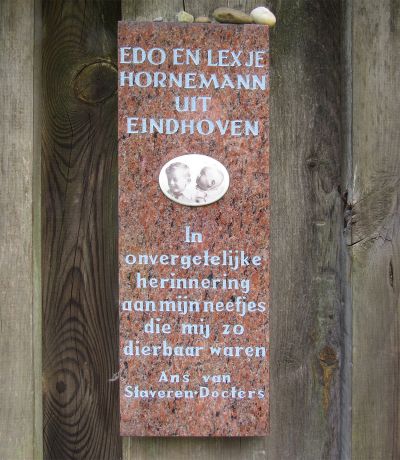

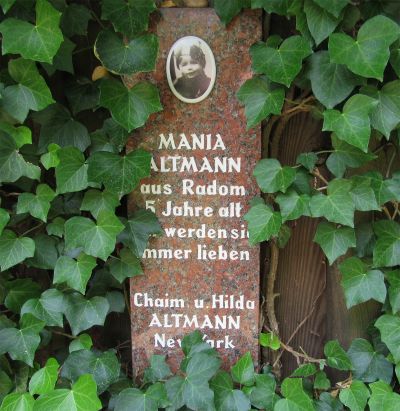

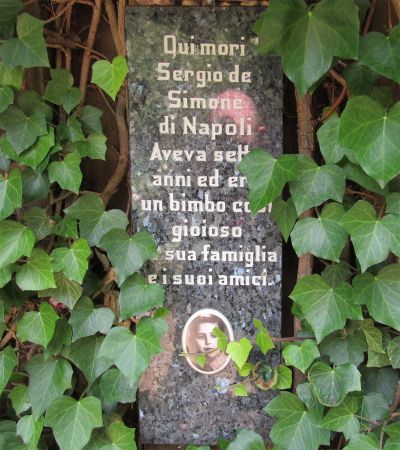

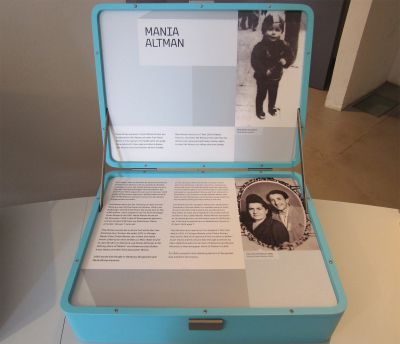

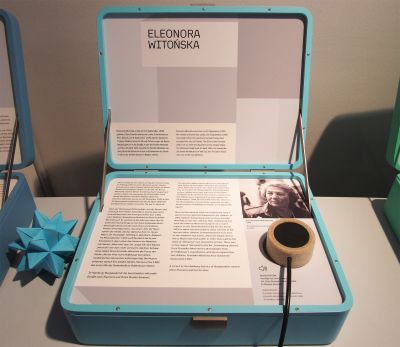

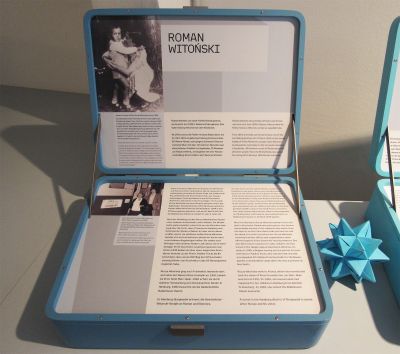

In 1979, as a result of the publication of the book, the aunt of Alexander and Eduard Hornemann, who lived in Eindhoven and who was the only member of the family to survive the war, found out about what had happened to her nephews. She remained in contact with the Association until her death in 2008, but refused to travel to Germany. In 1982, Rucza Witońska, who was by then married and known as Rose Grumelin, met Günther Schwarberg in Paris, and recognised her children Roman and Eleonora among the photographs he had brought with him. She travelled to Hamburg that same year. Since her death in 2012, her son Marc-Alain has regularly attended the memorial events. Also in 1982, the uncle of Mania, Chaim Altman, made contact with Schwarberg from the US, and came to Hamburg for the first time in 1986. In 1983, Gisella De Simone found out about the crime committed against her son Sergio. The following year, she attended the memorial event in Hamburg, although she refused to believe that her child had been murdered. Following her death in 1988, her younger son and his family attended the event in Hamburg every year on 20 April. In 1984, Ytzhak (Jerzy) Reichenbaum, who was living in Haifa, discovered the fate of his brother Eduard. From then on, he and his wife attended the memorial events at Bullenhuser Damm nearly every year, and also spoke to young people about what happened to their family.

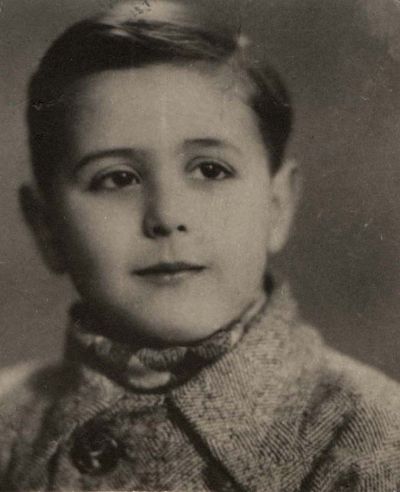

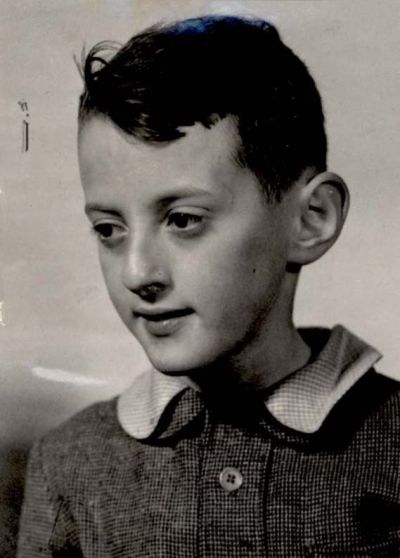

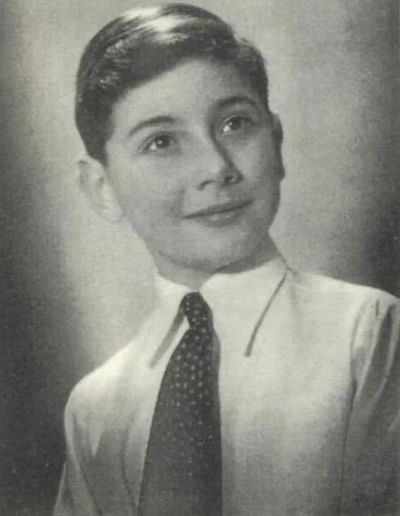

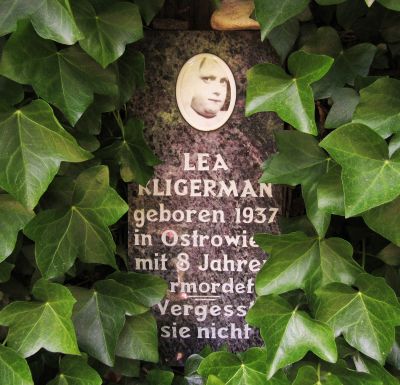

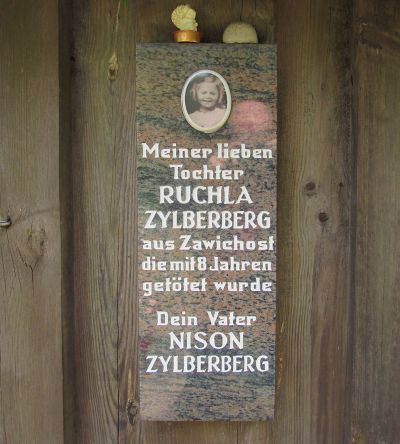

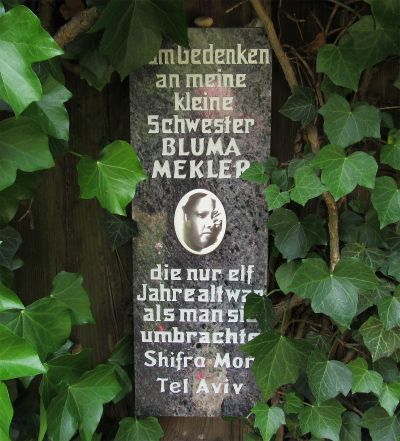

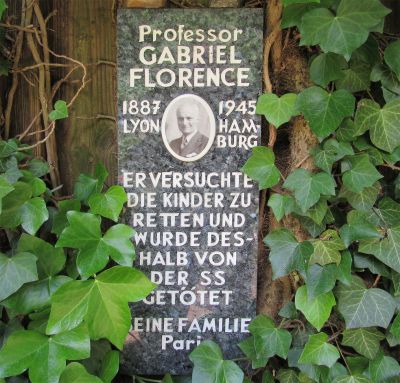

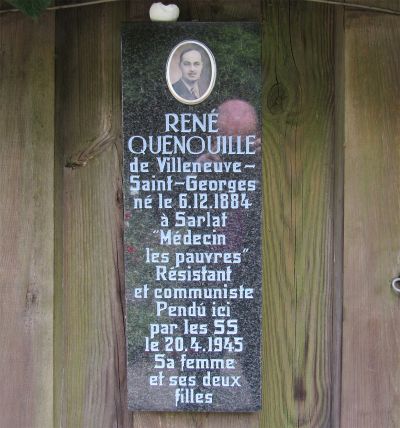

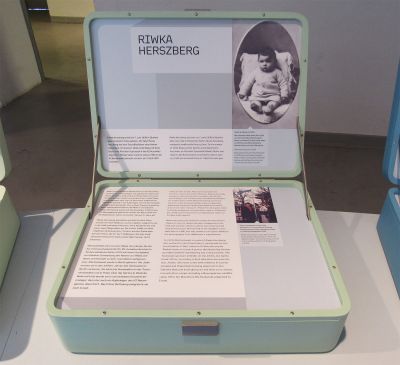

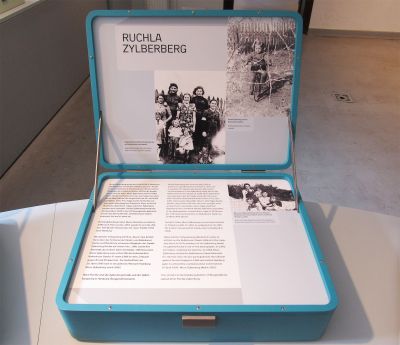

In 1983, in collaboration with the Association, pupils created the rose garden, which still exists today and which was also designed by the Hamburg artist Lili Fischer. In 1985, the Soviet Ministry of Culture arranged for a bronze sculpture by the Russian artist Anatoli Mossitzschuk to be erected at the entrance to the garden in memory of the Soviet prisoners who were murdered (Fig. 9 , 10 ). At the gate of the rose garden, a granite panel was erected for each child and for each of the doctors and carers, showing a photograph fired in porcelain, together with information about their age and place of origin as well as a personal dedication (Fig. 11–34 ).

In 1986, in order to document the failure of the German judiciary to deal appropriately with Arnold Strippel, the Association organised an international tribunal at the Bullenhuser Damm memorial site (Gedenkstätte Bullenhuser Damm). The multi-day event was attended by lawyers from the countries of origin of the victims and was chaired by the former German constitutional judge, Martin Hirsch. The aim of the event was to clarify why Strippel, one of the main suspects in the murder of the children, had not appeared before a court and why the Federal German judiciary in general prevented or delayed the pursuit of Nazi criminals. Excerpts from the protocols from the Curiohaus trials were read out, and statements were heard from relatives, witnesses, and experts. According to Schwarberg: “When Niso Zylberberg, the father of Ruchla, came forward, the thousand people present stood up in silence. He was unable to speak through his tears. Jizhak Reichenbaurn gave a description of his brother Eduard, while Margarete Wilkens spoke of Sergio De Simone and Chaim Altman of his small niece Mania. On 20 April 1986, the judges came to the following conclusion: ‘The failure to prosecute the criminals involved in the murders at Bullenhuser Damm is not an isolated case, but is exemplary of the manner in which the Federal German judiciary handles Nazi crimes. A state which fails to punish the crimes of the Nazi regime is vulnerable to new fascism’”.[46]

In 1987, in the stairwell of the memorial site, a wall painting was installed by Hamburg artist Jürgen Waller entitled “21 April 1945, 5 o’clock in the morning” (21 April 1945, 5 Uhr morgens). The painting depicts what the artist imagined the morning after the crime must have looked like (Fig. 35 ). In 1992, streets, a park, and a playhouse in the Burgwedel new residential area of Hamburg-Schnelsen were named after the children. In 1994, in collaboration with the Neuengamme concentration camp memorial site (KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme), the site at Bullenhuser Damm was given a new permanent exhibition. In 1999, it was established as a branch of the Neuengamme site, and thus came under control of the Hamburg municipality as part of the city’s cultural authority. Today, the memorial site is part of the Foundation of Hamburg Memorials and Learning Centres Commemorating the Victims of Nazi Crimes (Stiftung Hamburger Gedenkstätten und Lernorte zur Erinnerung an die Opfer der NS-Verbrechen). In 2000, a memorial stele by the Russian artist Leonid Mogilevski, with portraits cast in bronze and the names of the 20 children, was erected on Roman-Zeller-Platz in Burgwedel, which was named after the Polish boy R. Zeller (Fig. 36 ). In 2011, the Bullenhuser Damm memorial site was expanded and the exhibition was redesigned.

[46] Schwarberg: Kinder 1996 (see Bibliography), page 155