The “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”) 1938

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Alina Bothe - Kuratorin der Ausstellung "Ausgewiesen!" in Berlin

It is not known how many Jews paid with their lives for these transports and the flight into Poland via no-man’s land. By the time the government in Warsaw had finally permitted the deportees to enter Poland, many of them had already made it across the border. Within just two days, between 8,000 and 9,500 people, over half of whom were Jews of Polish origin who had been expelled from Germany, arrived in Zbąszyń, a town with a population of just over 4,000. From one day to the next, Zbąszyń became a vast refugee camp. It was simply impossible to provide shelter for such a large number of people. Some of them were housed in the station building, in the mill or in the former barracks, while others were forced to camp out in the open air. In time, people began taking Jews into their private homes.

In the interim, Poland began negotiations with Germany, requesting permission to return the deported Jews to the “Third Reich” and compensation for the possessions that they had lost, or for the transfer of these goods to Poland. Finally, in January 1939, it was agreed that the relatives of the deportees who were still living in Germany would be allowed to join them in Poland. Those who had been forced to leave their property behind were permitted to return to Germany for one month in order to put their affairs in order. To be able to do so, they were required to pay the capital obtained from the sale of their goods into frozen bank accounts in Germany.[24] After the Second World War broke out, they were no longer able to access their assets.

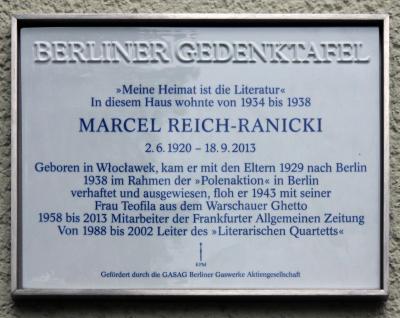

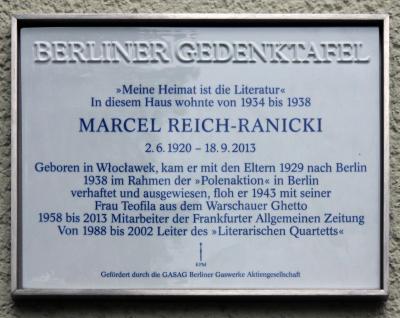

Anyone who was able, or rather, those who had sufficient funds, left Zbąszyń as quickly as possible and travelled further inland into Poland or emigrated to other countries. During the first few days, around two thousand people left the town, including Marcel Reich-Ranicki, who travelled to Warsaw with his family. The Poles and the employees of the Jewish charity organisations who were sent to Zbąszyń to help did all they could to provide halfway decent living conditions for those who remained behind. Blankets were collected and hot food and drinks were handed out. When the supply of bread ran out on the first day, the mayor of Zbąszyń set a fixed price for bread in order to prevent speculation and the inevitable price rises that would result for this valuable commodity.

Despite the lack of warmth felt towards the Jewish community in Poland at the time, the local population rushed to help the deportees: As Wojciech Olejniczak, chairman of the “TRES Foundation” (Fundacja TRES), whose work includes preserving the memory of what happened in Zbąszyń, recalls: “The sudden arrival of such a large number of hungry, freezing, clearly frightened people triggered a natural human desire to help among the locals.”[25] Many of the deportees who reported on the events many years later expressed their gratitude towards the local population for their humane solidarity. These accounts are stored in the archives by the American USC Shoah Foundation and the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem and elsewhere. In the words of the historian Jerzy Tomaszewski, who has also studied the events that occurred: “At that time, the people of Zbąszyń restored the honour of Poland.”[26]

The assistance for the Jews who were stranded in the small town in Greater Poland was funded mainly by Jewish charity organisations. Collections were also organised, in which the people of Zbąszyń were actively involved. Alongside the timely provision of accommodation before the outbreak of winter, the most difficult task was ensuring that the refugees were fed. While field kitchens had been installed in the barracks, people still had to wait in long queues before they were given a meal, and not all of them had warm clothes to wear.[27]

They also suffered from mental stress. The dramatic events, the separation from their families, the loss of their home and possessions and in many cases, their lack of knowledge of the Polish language, led to feelings of anxiety and loneliness. It was under these circumstances that small shops began to open in Zbąszyń that catered to everyday needs. Soon, hairdressers, tailors and cobblers appeared, followed by various manual trades, a separate post office and a sanitation service. The aim was to integrate as many of the deportees as possible into “normal” life and in so doing, prevent them from sinking into inactivity and apathy. Isaac Giterman, the Polish director of Joint Distribution Committee, an international aid organisation which provided assistance to the deported Jews on site, described the situation as follows: “At least everyone now has a pallet on which to sleep. The children and sick people get milk each day, there is enough linen to go round and some people have been given clothing. After beginning in total despair, there are now discussion evenings for Zionist youth groups and lessons in Polish. … The most moving plea came from the children, who asked if all under-16s could meet in a room so that they could play.”[28]