The “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”) 1938

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Alina Bothe - Kuratorin der Ausstellung "Ausgewiesen!" in Berlin

“We were only allowed to take the most basic essentials with us, and were brought to the station under constant guard. It is almost impossible to describe this feeling, but this moment still haunts me to this day. That day, we lost everything we had, our old life, our home and our family.”[1] This is how Siegfried Jaffe, who was 15 at that time, remembers the “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”). His parents, Erna and Lazar, had come to Germany from Galicia after the First World War. The fate of this young boy, who had been born in Berlin, was shared by thousands of Polish Jews at the end of October 1938.

The Jews had been the target of harassment long before the “Polenaktion”, however. Since Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933, their situation in the German Reich had systematically deteriorated. Anti-Semitism was not a new phenomenon either in Germany or elsewhere in Europe, but under the National Socialists, it became a state doctrine.[2] Repressive measures, incitement to hatred and the growing level of propaganda against Jews, as well as the boycotting of their participation in public life, had become an everyday occurrence. In total, around two thousand anti-Semitic laws and regulations that discriminated against people of the Jewish faith were passed and introduced in the “Third Reich”.[3]

The Jews living in Germany who originally came from eastern Europe, known derogatively as the “Ostjuden”, were in the particularly precarious position of being right at the bottom of the hierarchy of “unwanted” (i.e. Jewish – translator’s note) citizens. According to the census of June 1933, the population of the “Third Reich”, which at that time totalled 65 million, included around half a million Jews, of whom 100,000 did not have German citizenship. By far the largest proportion of this group (60,000) were Polish citizens, while a further 20,000 were of Polish origin.[4] Most Jews of Polish origin had come to Germany during the chaos of the First World War from 1914–1918. Some had arrived as prisoners, while others were forced labourers or economic migrants. For others, Germany was originally intended only as an intermediate stop en route to the United States. However, in the end, they had remained there since for various reasons they were unable to make the journey across the ocean.[5]

The unceasing acts of violence, the restriction of their citizens’ rights and the introduction of employment bans against the Jews meant that their living conditions as a group within society deteriorated continuously and they lived their lives in constant fear. As a result, they emigrated to different countries in increasing numbers. By 1938, around 250,000 Jews had left the German Reich.

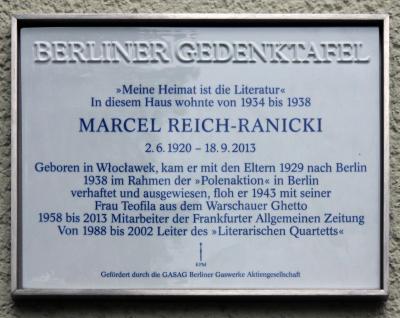

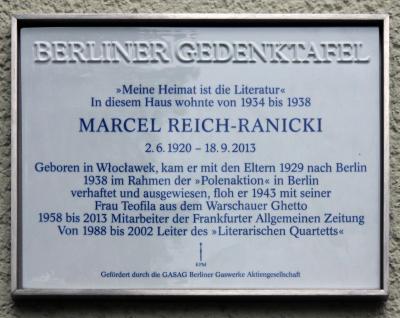

For the National Socialists, who had already publicly stated at an NSDAP meeting in 1920 that they intended to “liberate” Germany from all its Jewish citizens, the campaigns against them were progressing far too slowly. When 200,000 more Jews became citizens of Germany following the annexation of Austria on 12 March 1938, the Polish government suddenly and unexpectedly played a part in triggering the events that followed, namely the “Polenaktion”. On 31 March 1938, fearing a wave of impoverished Jewish immigrants seeking refuge in Poland from the anti-Semitic environment under the National Socialists, the Polish Sejm passed a law on the withdrawal of citizenship (Ustawa o pozbawieniu obywatelstwa)[6]. The law stated that any Polish citizen living abroad would have their Polish citizenship revoked “if they have lived abroad for longer than five years following the founding of the Polish state”, or “have lost their connection to the Polish state”[7]. Furthermore, it was decided that the revocation of citizenship of a husband should also extend to that of his wife, and of a father to his children aged 18 or younger “if these persons are living abroad, and if they have not been excluded from the revocation of citizenship in the official revocation decision.”[8]

The German government issued an immediate protest against the new law via diplomatic channels. However, the new regulations were only reluctantly introduced. It was only six months later, on 9 October 1938, that the decision by the Polish government to order mandatory consular stamps in the passports of Poles living abroad was put into action. The consuls were also ordered to retain the passports of those whose citizenship was to be revoked. Passports that did not have a consular stamp automatically expired on 30 October.[9] At that time, the Germans were afraid that soon, there would no longer be anywhere they could send the Jews, particularly since other countries had already closed their borders to them.

[1] K. Dressel, N. Wegt, “An diesem Tag verloren wir alles, was wir gehabt haben”, in: Ausgewiesen! Berlin, 28.10.1938. Die Geschichte der “Polenaktion”, edited by Alina Bothe and Gertrud Pickhan, Berlin 2018, p. 185.

[2] Michael Wildt, “Volksgemeinschaft” als Selbstermächtigung. Soziale Praxis und Gewalt, in: Hitler und die Deutschen. Volksgemeinschaft und Verbrechen, Berlin 2010.

[3] Ausgrenzung und Verfolgung der jüdischen Bevölkerung, at: LeMo Lebendiges Museum Online, https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/ns-regime/ausgrenzung-und-verfolgung.html

[4] Miriam Rürup, Wie aus Deutschen Juden wurden, in: Ausgewiesen!..., p. 53.

[5] Gertrud Pickhan, Generalprobe für die Deportation, at: Tagesspiegel.de, 24/10/2013.

[7] Ustawa o pozbawieniu obywatelstwa [Law on the revocation of citizenship] 31 March 1938, Article 1b.

[8] Ibid., Article 3.1.

[9] Jerzy Tomaszewski, Przystanek Zbąszyń, in: Izabela Skórzyńska, Wojciech Olejniczak (ed.), Do zobaczenia za rok w Jerozolimie. Deportacje polskich Żydów w 1938 roku z Niemiec do Zbąszynia, (Polish-English dual language edition), Fundacja TRES, Zbąszyń - Poznań 2012, p. 73.