The “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”) 1938

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Alina Bothe - Kuratorin der Ausstellung "Ausgewiesen!" in Berlin

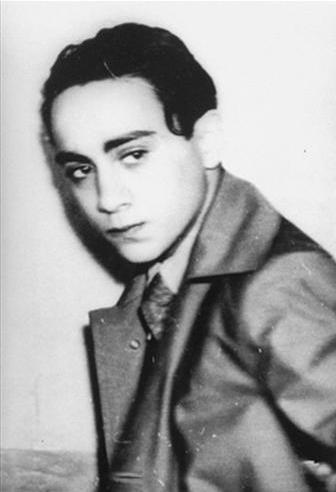

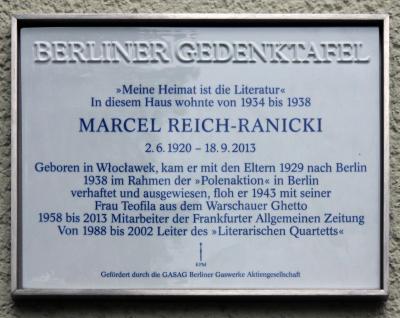

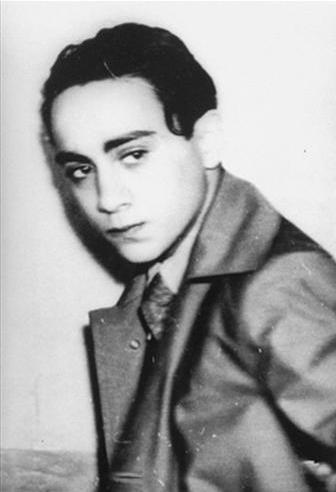

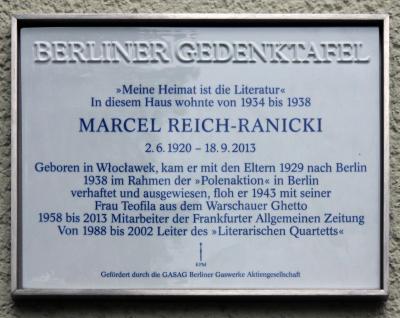

One common characteristic for many deportees with Polish citizenship was that they felt themselves to be German. This was also true of Marcel Reich-Ranicki, who had to leave Germany at 18 during the “Polenaktion”. Reich-Ranicki, who later became known as the “Pope of Literature”, was born in Włocławek in 1920. Of himself, he said that he was “half-Pole, half-German and whole-Jew”. He had left Poland aged nine, when his family, who suffered from financial difficulties, moved to Berlin. As was the case with all Jews, Ranicki’s rights were severely curtailed following the seizure of power by the Nazis. While in 1938, he was still permitted to take his “Abitur” school-leaving exam, his application to enrol as a student at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin (renamed Humboldt-Universität after the war) was rejected due to his Jewish origins.

Several months later, on 28 October, shortly before seven in the morning, the police knocked on the door of the tiny room where the family lived at 16 Spichernstrasse, in the Berlin district of Wilmersdorf. The 18-year-old Ranicki was handed a document ordering him to leave Germany within 14 days. However, the order was carried out immediately. “Needless to say, I had to leave everything behind that I had in my little room. I was only allowed to take five marks with me, as well as a briefcase. But I did not quite know what to put in it. In the hurry, I put in a spare handkerchief and something to read.”[20]

At first, Ranicki suspected that someone had denounced him; he was unaware of any reason for being arrested, and the situation felt utterly unreal. He later discovered that the only “reason” was his Polish origins. In his autobiography, “The Author of Himself. The Life of Marcel Reich-Ranicki”, which was published decades later, the famous literary critic describes the others who were deported as follows: “They were Jews and all older than me, the eighteen-year-old. They were speaking perfect German and not a word of Polish. They had either been born in Germany, or had come to Germany as small children and attended school there. But like me, they all, as I soon discovered, had Polish passports.”[21]

We have Marcel Reich-Ranicki’s memoirs to thank for one of the most detailed descriptions of the expulsion of the Jews: “We were not told where the train was going, but it was soon clear that it was going east – to the Polish frontier. We were freezing, the carriages were not heated, but everyone had a seat. Compared to subsequent transports, these were humane, almost luxurious, conditions. (...) At the German frontier, we had to get off the train and form up in columns. There were shouted commands, many shots, shrill screams in the darkness. Then a train arrived. It was a short Polish train, into which the German police now brutally drove us. The carriages were crammed full. The doors were immediately slammed shut and sealed, and the train pulled out.”[22]

The trains carrying the deportees from Germany arrived in Beuthen (Bytom), Konitz (Chojnice) and Kreuz (Krzyż). For most of the Jews, the journey continued on to the final stop in Zbąszyń, the small town which after the re-establishment of the Polish state found itself directly on the border with Germany. The first trains were able to travel across the border, since the Poles were entirely taken unawares: the imminent wave of expulsions was not reported to the border guards, nor to the local authorities in the towns and villages close to the border. However, as an ever-increasing number of trains continued to arrive, the Polish authorities first refused to allow them into Poland, and they were forced to stop several kilometres before the border, in no-man’s land. From there, the Jews were chased through forests and swamps towards Poland, accompanied by threats and under fire by the Nazis. “We had no knowledge either of where this path was taking us, or of what fate held in store for us. Hours later, we spotted a white-and-red striped barrier that crossed the path, and as we came closer, a Polish flag. Near the border, there were swamps and muddy wetlands on both sides of the path. This was the ‘no-man’s land’ between Germany and Poland. Suddenly, the Germans began shooting at the long column of Jews – men, women and children. We fled into the wetlands. My father pulled me down and pushed my head deep into the mud. At that moment, I thought that my beloved father was trying to drown me! Finally, the shooting stopped. Covered in mud, we slowly crept out of the swamps, waded through the river and reached Polish territory. Six Polish border officials – and no more – faced the armed German soldiers.”[23] This is how Willi Najman, who was nine years old at the time, and whom the German police collected from his school in Hamburg before deporting him and his family, remembered his journey to Zbąszyń.