The “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”) 1938

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Alina Bothe - Kuratorin der Ausstellung "Ausgewiesen!" in Berlin

The “Polenaktion” was the first mass deportation of the Jews from the “Third Reich”. It was carried out entirely in the open, and the German population would have been fully aware of it. By that time, anti-Semitic sentiment was so widespread in society that the arrests were met with silent agreement and sometimes even open enthusiasm. As Mendel Max Karp recalled: “One truck after the other left the barracks courtyard with us in them, a long chain of monstrous vehicles snaked across the “Alex” [Alexanderplatz – author’s note] and through the city, accompanied by the deafening din of sirens, sounded intentionally to alert the population of Berlin to our forced deportation. The people amassed in the streets, witnesses to the ‘historic’ expulsion of the Jews from Germany.”[15]

In effect, the “Polenaktion” was a logistical dress rehearsal for the National Socialists in order to determine how smoothly the state organs were able to carry out the deportations. And even though the campaign involved an enormous amount of effort, not everything went according to plan. This was the case in Leipzig, which at that time was home to over three thousand Jews of Polish origin. They accounted for a third of the Jewish population in the city. The Consul General of Poland in Leipzig, Feliks Chiczewski (1889–1972), had long been aware of the increasingly difficult situation for the Jews in Germany. Just two days before the “Polenaktion”, Chiczewski sent a report to the Polish Ambassador in Berlin, Józef Lipski, in which he described the intensification of the measures against members of the Jewish faith as a “war that has been declared against the Jews by the National Socialist party and which will inevitably end with their complete destruction”[16].

When news of the first arrests in other cities in the Reich reached Leipzig, the diplomat attempted to negotiate an agreement with the police and the local authorities whereby women, children and the sick were to be excluded from deportation. The Chief of Police initially agreed to the proposal, although on condition that the Jews to be deported were able to provide proof that they wanted to leave Germany anyway. However, when the negotiations stalled, Chiczewski informed all the Polish Jews that they must present themselves at the consulate. Those who had a telephone informed their families, friends and acquaintances, and within just a short space of time, around 1,300 people arrived at the villa where the consulate was housed in Wächterstrasse 32.[17] A report from that time states the following: “The entire large garden, all the entrances, the stairs, the waiting room, the cellar rooms and a portion of the private chambers of the Consul and the laundry buildings were full of refugees.”[18]

By taking the Jews into the consulate premises, Chiczewski guaranteed them extra-territorial protection. He also issued them with passports, regardless of their residential status. The Gestapo, which was based in the same street, did not dare to intervene on the entire consulate site, since it was regarded as inviolable. The Jews saved by Chichzewski on 29 October then left the villa in Wächterstrasse and returned to their homes. Many of them did indeed leave Germany shortly afterwards. Those who were unable to seek refuge in the consulate were arrested by the police and taken to the main railway station. From there, they were transported in four trains to Beuthen (now Bytom), where they were chased across the border.

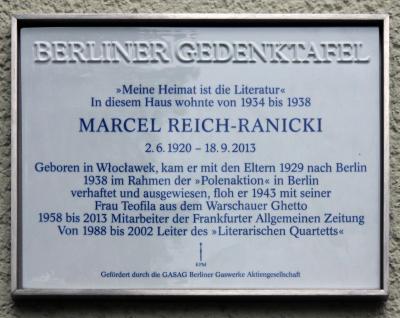

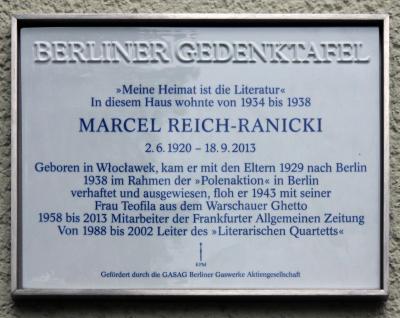

In the space of just two days, over 17,000 Jews were expelled from the “Third Reich”. The numbers deported from individual towns and cities are based only on estimates: 1,500 from Berlin, 1,000 from Hamburg, including women and children, 600 from Dortmund and Cologne, 420 from Essen, 361 from Düsseldorf and 70 from Gelsenkirchen.[19] In spite of all this, until recently, only a small number of people were aware of the existence of the “Polenaktion”, even though there were some individuals who became highly successful in later life among the deported.

They included Gerhard Klein (1920–1999), who was 18 at the time, and who was a young star in film and on stage. He became famous in the role of the professor in “Emil und die Detektive”, a play based on the novel of the same name by Erich Kästner which was popular at the time. Klein performed at the Berliner Theater, the Jüdisches Theater (Jewish Theatre) and the Kindertheater des Kulturbundes (League of Culture Children’s Theatre), among others. He also played a lead role in the 1931 film “Dann schon lieber Lebertran” (In that Case, I’d Prefer Cod-Liver Oil) by Max Ophüls, before his career came to a halt when the National Socialists came to power and prohibited actors of Jewish origin from working. Like his brother, Gerhard Klein was born in Berlin. Both siblings had nothing to do with Poland and did not even speak Polish. It was because of their father, who was born near Oświęcim (Auschwitz) that they had Polish citizenship. Nevertheless, they were forced to leave Germany and move to an unknown country.

[16] S. Held, Leipziger Geschichte(n): Generalkonsul Chiczewski warf einen Rettungsanker aus, in: Leipziger Volkszeitung, online edition of the newspaper, 26/10/2013.

[17] A. Lustiger, Rettungswiderstand. Über die Judenretter in Europa während der NS-Zeit, Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2011, p. 72.

[18] Quoted from: J. Tomaszewski, The Expulsion of Jewish Polish Citizens, in: Acta Poloniae Historica 76, 1997, p. 106.