The “Polenaktion” (“Polish Action”) 1938

Mediathek Sorted

Interview mit Alina Bothe - Kuratorin der Ausstellung "Ausgewiesen!" in Berlin

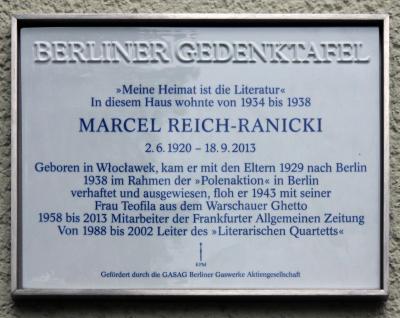

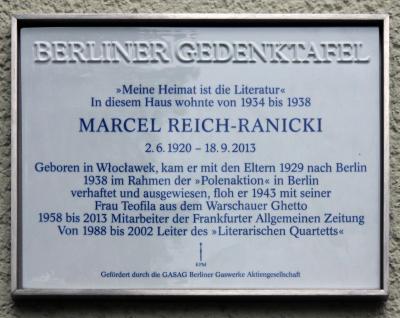

A response to the measures taken by Poland came on 26 October, when Heinrich Himmler, head of the German police and Reichsführer-SS, issued the order that all Jews of Polish origin should be expelled from the “Third Reich”. The operation was very carefully planned, and involved a coordinated effort between the SS, the Gestapo, the Deutsche Reichsbahn railway company and diplomatic staff. The responsibility for coordinating the “Polenaktion” lay with the interior ministries of the constituent states (“Länder”). Propaganda in support of the campaign was published by the German press, which also reported, among other things, that the Polish state had “demanded” that the Jews return to their homeland. One example is the article published in the “Rheinisch-Westfälische Zeitung” newspaper in Essen: “A large proportion of the Jews came to Germany after 1918; many Jews from Poland and East Galicia also came to Essen. Since these Jews remained Polish citizens, the Polish state ultimately had no other option than to demand that they now return, and in the event of their refusal, to immediately withdraw their Polish citizenship.”[10]

Himmler’s order was immediately put into practice. The first arrests were already made on 27 October, particularly in the west of the country. However, most of the measures were carried out on 28 and 29 October. The arrests followed the same protocol nearly everywhere. In most cases, officials entered the homes of the people in question in the early hours of the morning, issuing a demand to the astonished residents that they must leave the territory of the German Reich within 24 hours. “We were not, however, granted this period of time and had to follow the officers as soon as we had dressed and were given next to no time to take along clothing and linens. I was forced to leave Germany meagrely clothed and with just a few Reichsmarks.”[11] This is how the Berlin violinist Mendel Max Karp described what happened in a letter to his brother, which he wrote shortly after arriving in the transit camp in Zbąszyń (Bentschen). His detailed report is one of the earliest contemporary witness documents of that time. The majority of the deportees, if they survived the Holocaust at all, only spoke about the dramatic events that occurred decades later.

In Berlin, it was mainly men aged over 15 who were expelled, while in other parts of Germany, entire Jewish families were deported, including children, the elderly and ill family members. Max Karp wrote: “After the people had been gathered in Berlin, we were brought to a freight depot in Treptow in half-enclosed or partially covered trucks under the supervision of the police barracks. In front of the barracks and in the neighbouring streets, emotional scenes took place among the women, mothers, and children left behind in Berlin.”[12]

The report by Ottilie Schoenewald from Bochum, the wife of the chairman of the Jewish community and a member of the board of the Jewish women’s league, was no less disturbing: “The line of cars drove to all the Jewish butchers, bought all the kosher sausages they had, then on to the bakers, who promised to set aside several hundred fresh rolls the following morning. (...) The person on watch, whom I knew, told me that we should eat our food at the station, (...) At the station, a seething mass of flustered, crying, screaming women and children had already gathered, and new cars kept arriving and literally ‘shook’ their miserable occupants out onto the square. (...) When at around 10:30 in the morning we heard ‘everyone onto the platform’ we were overcome by real mass hysteria. Everyone started pushing and shoving, even though in reality, no-one had wanted this moment to arrive. Mothers screamed at their children who were holding their hands or holding onto their skirt hems. The children were crying for their mothers. Every so often, there were people who requisitioned items left behind by someone else.”[13]

The recollections recorded by Ottilie Rimpel from Stuttgart, which have been passed on by her son, are just as disturbing: “We were a group of people in a desolate state – without any idea of what was happening, without luggage – with nothing but the clothes on our backs. We were just the kind of people that Hitler once spoke of in his speech in the market square in Stuttgart. He said: ‘We will throw all the dirty Polish bloodsuckers together with their lice out of here, without clothes and without a penny in their pockets.’ I regret the fact that we didn’t listen to what he was saying at that time, and that we hadn’t read his book ‘Mein Kampf’ and taken it to heart. This odious man was fully aware of everything that he wrote and said. The people called it propaganda. However, it was the bitter truth, as we would later find out.”[14]

[11] Weblog on the website of the Jewish Museum Berlin: https://www.jmberlin.de/en/topic-polenaktion-1938

[14] Ottilie Rimpel’s memories are included in the book: Wojciech Olejniczak, Izabela Skórzyńska (ed.), Do zobaczenia za rok w Jerozolimie..., p. 145–146.