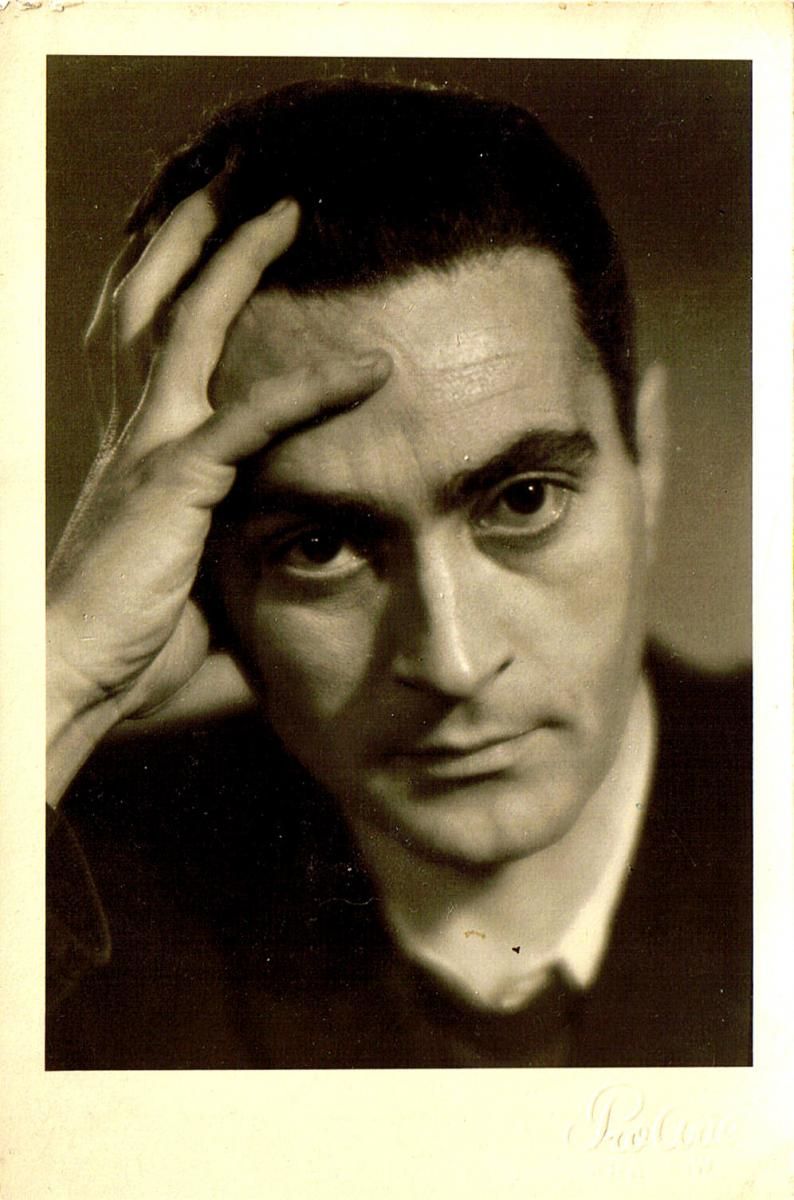

Zdzisław Nardelli

Mediathek Sorted

![His debut as poet His debut as poet - „Świt na nowo” [Daybreak Anew], tomik poezji [volume of poetry], editor, F. Hoesick. Warsaw 1938, and poem entitled “Wyjazd” [Departure].](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/1._nardelli_swit_okladka_0.jpg?itok=XtuveBzH)

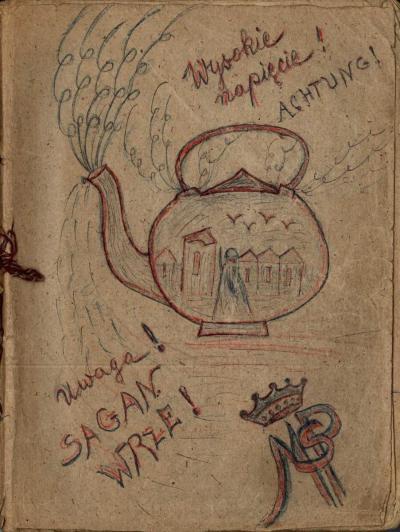

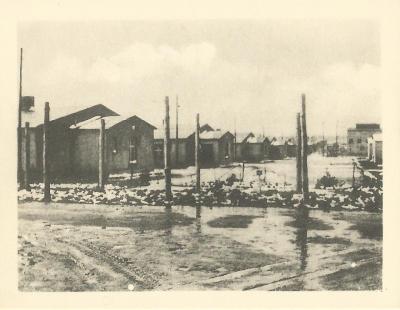

![Stalag VIII C in Sagan Stalag VIII C in Sagan - Reprint from the folder: Muzeum Obozów Jenieckich [Prisoner of War Camp Museum]. Stalag VIII C. Stalag Luft 3, edited by Muzeum Obozów Jenieckich, Żagań [Sagan] 2014.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/2._zagan_folder.jpg?itok=rMCH1RCU)

![Page with the triangular censor seal ‘tested’ of Stalag VIII C in Sagan Page with the triangular censor seal ‘tested’ of Stalag VIII C in Sagan - ‘Oczko we mgle...’ [A Tiny Eye in the Fog], in: ‘Szopka Sagańska’.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/4._szopka_saganska.jpg?itok=EzGpZ0FL)

![Caricature of Zdzisław Nardelli Caricature of Zdzisław Nardelli - In: “Szopka Sagańskiej” [Sagan Nativity Play].](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/5._nardelli_karykatura.jpg?itok=koe6bqgv)

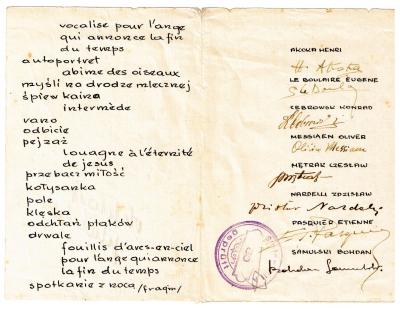

![‘Wieczór polski’ [Polish Evening] in Stalag VIII A in Görlitz ‘Wieczór polski’ [Polish Evening] in Stalag VIII A in Görlitz - The programme of the Polish Evening (cover), created by Bohdan Samulski.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/8._wieczor_polski_1940_program_s._1-4_600dpj.jpg?itok=ZrxNTYFw)

![Zdzisław Nardelli in the film by Antoni Bohdziewicz “Za wami pójdą inni…” [Others will be following you] Zdzisław Nardelli in the film by Antoni Bohdziewicz “Za wami pójdą inni…” [Others will be following you] - The only existing film reel in the FN..](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/15._z._nardelli_w_filmie.jpg?itok=HiQspfto)

![“Pasztet z ojczyzny” [A Pie from the Homeland] “Pasztet z ojczyzny” [A Pie from the Homeland] - Cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/20._nardelli_pasztet_okladka.jpg?itok=awWM9OsG)

![Dedication written Zdzisław Nardelli for Jerzy Stankiewicz Dedication written Zdzisław Nardelli for Jerzy Stankiewicz - In a copy of “Otchłań ptaków” [The Birds’ Hell].](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/22._nardelli_1989_dedykacja.jpg?itok=LszHQZ-E)

![“Płaskorzeźby dyletanta” [The Bas-Relief of a Dilettante] “Płaskorzeźby dyletanta” [The Bas-Relief of a Dilettante] - Cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/23._nardelli_plaskorzezby_okladka.jpg?itok=O3spRHrT)

Because he was a writer, Zdzisław Nardelli was given responsibility for looking after the camp library. As a prisoner he had shown great strength of character, spoke fluent German and could deal with the Germans on an everyday level in a relatively relaxed manner. In mid July 1940 the composer Olivier Messiaen arrived in the camp on one of the many transport trains carrying French prisoners-of-war. He was soon to become one of the most famous composers of the 20th century. His imprisonment was to become a symbol of European culture: his Quartet for the End of Time the work he composed and performed in the camp aroused immense interest. Two other great musicians, both of them members of Paris orchestras, also arrived in the camp with Messiaen. The cellist Etienne Pasquier, was appointed to a labour group working in the quarry at Strzegom. Another, a priest by the name of Jean Brossard (detainee number 908), was on the same transport as Messiaen. He was to become the chaplain to the French POWs and was also given heavy labour duties in a more distant area away from the camp.

Here Messiaen’s friends requested the Poles to ensure that their talented comrades would be spared a similar fate. Nardelli decided to appoint Messiaen as his library assistant and succeeded in getting the consent of the camp commandant. The French composer was thus saved from backbreaking forced labour and could find refuge and peace in the Polish library, where he was free to think, meditate and work on new compositions. His arrangements were specially written for the musicians imprisoned in the Stalag, i.e. for violin, clarinet, cello and grand piano (here replaced by the camp piano). The Germans left Messiaen in peace: but it took some time before they truly realised the format and status of the personality interned in the Görlitz camp. The upshot was that Messiaen began to receive discrete help from the Germans, in particular from an NCO by the name of Karl-Albert Brüll, who was probably acting on his own initiative. Brüll was a lawyer by profession. He came from a respected notary’s family in Görlitz and was employed as an interpreter in the camp. He supplied Messiaen with manuscript paper, pencils and erasers, not forgetting food.

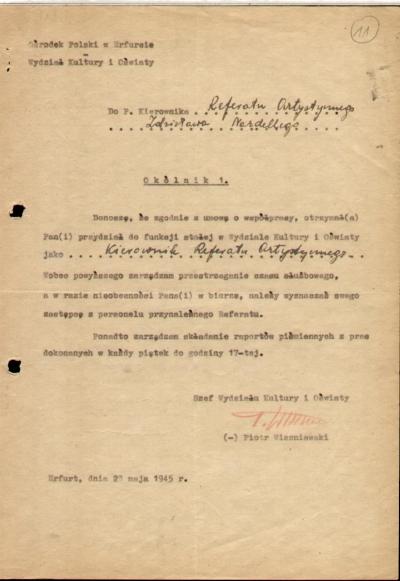

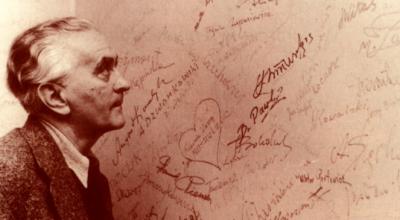

Nardelli’s next initiative was to organise a “Polish Evening” in mid December 1940, and to give it more status he invited Messiaen and the French musicians to attend. Along with Czesław Mętrak and Bohdan Samulski, Nardelli recited 13 poems he had written in the camp. Messiaen also agreed to play five works he had composed there. At the time nobody knew that these were parts of a work that was to later conquer the world: the Quartet for the End of Time. Bohdan Samulski produced a few dozen hand-written programmes, signed by the Polish promoters and the French musicians. Everything was marked by the camp censor with the seal “checked”. This precious document that bears witness to the premiere of fragments from the unfinished and unnamed Quartet written by Messiaen in the camp on the initiative of Polish POWs remained exclusively in Polish hands: with Zdzisław Nardelli and Czesław Mętrak in Warsaw, and Antoni Śliwiński in Kraków.

„This evening was one of the most interesting events that has ever taken place in the camp. Lieutenant Bull [Carl-Albrecht Brüll] stated that the concert was stirring and unique, the music by Olivier [Messiaen] difficult, gripping and utterly fitted to the poetry by the Polish poet, [Nardelli] – two similar contents expressed in different forms. Piskorz [Nardelli] recited slowly and with urgency. He treated the interpretation as simply as possible …

Kiedroń was fascinated by the music, grouped by the beauty of his new discoveries, the limitless possibilities of sounds. For the first time in his life he had come up against a form of music which he was unable to shake off and which went under his skin. He had never before imagined that music could cause wounds like broken glass. The listeners were caught in a balancing act of emotions and sent to the edge of an aesthetic climax. Messiaen dissolved traditional forms. They were too narrow for him. This was Kiedroń’s first encounter with such music. He didn’t know how he could find his way through it. He sensed its greatness and his shameful ignorance. He felt simply helpless in the face of it. The musical talents of the interpreters gave the glorious nature of the work an additional brilliance. In particular the incredible virtuosity shown by Akoka, who played the complicated score with the song of a canary and took the sound of the clarinet into a realm far removed from everyday reality. He was accompanied by Etienne Pasquier on cello, Le Boulaire on violin, and by the composer himself on piano: all of whom were masters on their own particular instruments.

Hence it was entirely unsurprising that the dying of the final chord was accompanied by great applause from the audience who surrounded the musicians and the astonished Messiaen. [Piskorz] thanked Bull for his friendly words, and in doing so he smiled sadly. Filled with bitterness he returned to his library behind the stacked up books. He was accompanied by Messiaen, who was all the more in need of a little peace and quiet …”