The children of Bullenhuser Damm

Mediathek Sorted

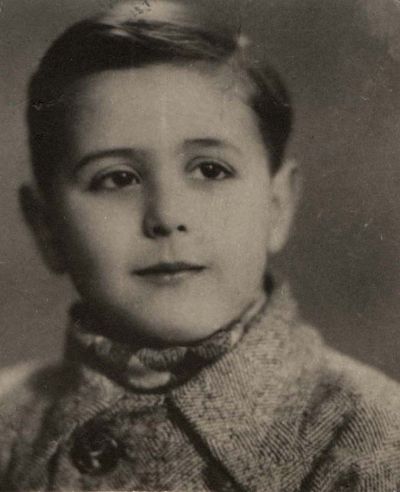

R. Zeller, a boy from Poland aged twelve, was probably born in 1933. His surname, age, gender, and place of origin are only known from the list published by Dr. Henry Meyer in Copenhagen in 1945 in the book “Rapport fra Neuengamme”. The camp doctor Kurt Heißmeyer also noted the initials R.Z. on one of his records, and used them to label one of the photos documenting his experiments with the children.

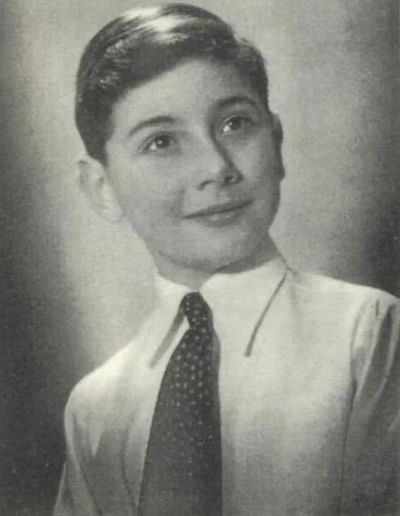

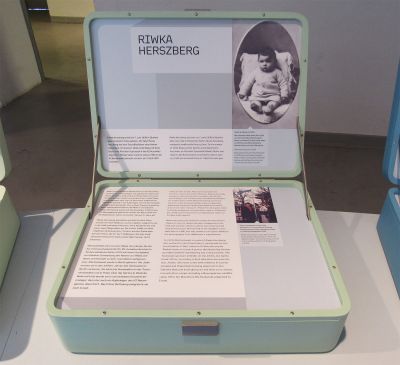

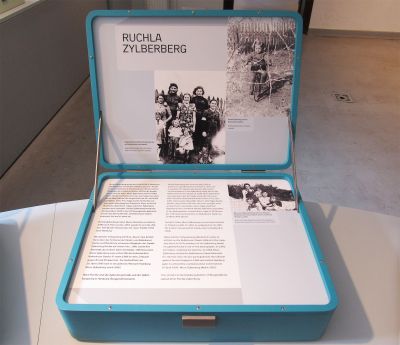

Ruchla Zylberberg was born on 6 May 1936. She was the daughter of Fajga, née Rosenblum, and Nison Zylberberg, a shoemaker, in the small Polish town of Zawichost, to the north of Sandomierz. Her sister Ester was born two years later. When the German Wehrmacht occupied Poland in 1939, her father fled to Russia with his brother and sister-in-law. He had originally planned to bring his family there at a later date, but this became impossible when the Germans attacked the Soviet Union. In 1942, the mother and daughters were taken to Auschwitz concentration camp, where Fajga and Ester were murdered. Ruchla was eight years old when she was taken to Neuengamme on 28 November 1944. Her father returned to Poland in 1946, and emigrated to the US in 1951. In 1979, his brother Henryk, who lived in Hamburg, was the first person to recognise Ruchla from a photograph in a press report about the children of Bullenhuser Damm. Nison Zylberberg confirmed the identity of his daughter. He died in 2002.

Human experiments on prisoners and children in the Neuengamme concentration camp

In the spring of 1944, leading medical experts from the German Reich government and members of the SS gathered for an informal meeting in the casino of the Heilanstalten Hohenlychen complex, which, from 1902 to 1945, was used as a clinic, in the town of Lychen in the Uckermark region of north Brandenburg. As well as housing the clinic itself, which originally specialised in the treatment of lung diseases, and more recently sports and occupational injuries, Hohenlychen also became a fashionable destination for prominent figures in the Nazi party, including Hitler and his ministers, as well as high-ranking members of the SS, generals and officers from the Waffen-SS, Reich officials, Reich sports leaders, state secretaries, and army officers. International delegations travelled there, too. The meeting in the spring of 1944 was attended by the Reich Health Leader Dr. Leonardo Conti, the Reich physicians’ leader for the SS and police, Dr. Ernst-Robert Grawitz, and the head physician at Hohenlychen, Prof. Dr. Karl Gebhardt, among others. At the meeting, a senior physician at the clinic, Dr. Kurt Heißmeyer, was invited to give a brief lecture.

Heißmeyer, who was born in Lamspringe in 1905, had earned his doctorate in Freiburg and had worked at Hohenlychen since 1938. His uncle, August Heißmeyer, was a Waffen-SS general. He was a friend of Oswald Pohl, a Waffen-SS general in the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-Wirtschafts- und Verwaltungshauptamt), who was responsible for the concentration camps. In order to gain his professorship, he was required to write a habilitation paper in which he aimed to tackle the treatment of tuberculosis. In his lecture, he suggested conducting a series of experiments on humans, in which patients suffering from tuberculosis were to be artificially infected with another tuberculosis pathogen. This was to be done by rubbing killed tuberculosis bacilli into a scratch on the skin, similar to administering a vaccine. This long-since debunked research approach originated from the Austrian doctor Hans Kutschera-Aichbergen, and was intended to improve immunity and healing in the lungs. Conti, Grawitz, and Gebhardt agreed that Heißmeyer should conduct the planned experiments on prisoners at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where Gebhardt had already experimented in various ways on prisoners, most of them women, since July 1942. However, approval was required from Reich Minister of the Interior Heinrich Himmler, who had reserved the right to issue permission for all human experiments, before the plan could go ahead. Finally, Pohl received Himmler’s consent, but only on condition that the tests were not conducted in Ravensbrück, since news had already reached the international community about Gebhardt’s experiments there. He and Heißmeyer decided that the Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg would be a somewhat “more discreet” place in which to conduct the trials.[7]

[7] Schwarberg: SS-Arzt 1997 (see Bibliography), page 9–14. See also Sterkowicz 1977/2021, see Bibliography and Online)