Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890

Mediathek Sorted

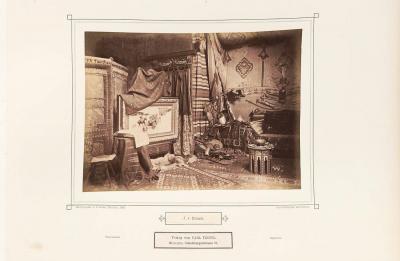

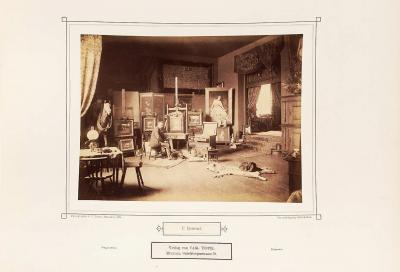

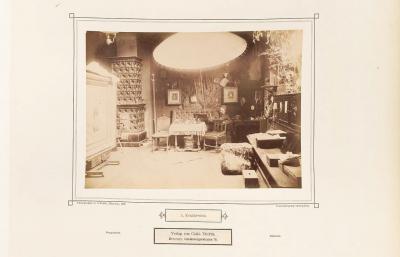

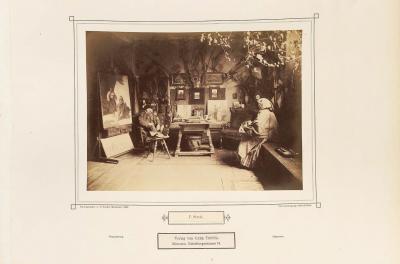

The decorations in the Munich ateliers were not just aimed at the initiated local public, they were also intended for tourists, foreign collectors and potential buyers, and were a fundamental part of the artists’ business models. Lenbach opened his atelier predominantly for aristocrats travelling through, Kaulbach showed his collection of Italian Renaissance paintings at set opening times. From the end of the 1870s, Munich address books listed the addresses of the artists’ ateliers in their own category along with the specialist area of each respective painter and their opening times. Travel guides for Munich in English in the 1880s‑ and 1990s‑ specifically made reference to the atelier of the Polish battle painter von Brandt, “a particularly successful master of the exotic genre and owner of an extraordinary atelier well worth seeing”.[49] In 1876, based on the idea of the costume parties that Makart held in his atelier in Vienna and for which he provided the models for the historical costumes,[50] the Munich artists celebrated Carnival in Munich in keeping with the motto “A court festival for Karl V”, which Makart and members of the Bavarian royal family also attended. Requisities from Brandt’s atelier were used at the party, with Brandt providing a Turkish troupe with costumes, which caused a sensation.[51]

In the mid-1870s, the Munich city guides and the international press listed the artists’ ateliers as Munich tourist attractions which were not to be missed. This led to streams of visitors and caused many artists to only open their atelier upon request or to shut up shop completely.[52] Brandt’s atelier mainly served as a meeting point for the Polish artist community. His circle, spread over about fifty years, included Ludwik Kurella (in Munich 1861-97), Henryk Redlich (1863-69), Szerner (1865-1915), of course, and Ajdukiewicz (1873-75), Maksymilian (1867-74) and Aleksander Gierymski (1868-97), Stanisław Szembek (1868-71), Ludomir Benedyktowicz (1868-72), Władysław Czachórski (1868-1911), Franciszek Streitt (1871-90), Antoni Kozakiewicz (1871-1900), Henryk Piątkowski (1872-75), Jan Rosen (1872-95), Jan Chełmiński (1873-76), Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski (1873-1915), Julian Fałat (1875-81), Franciszek Ejsmond (1879-94), Bohdan Kleczyński (1882-88), Szymon Buchbinder (1883-97), Apoloniusz Kędzierski (1886-89), Olga Boznańska (1886-98) and many others.[53]

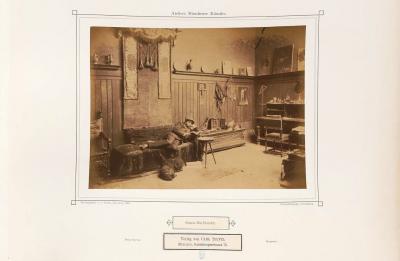

The artists all lived in the same streets in Ludwigsvorstadt and Maxvorstadt and in Schwabing. They had their painting studios at the academy, in their apartments or in rear buildings occupied only by ateliers in these streets. They studied and worked together, met for lunch or dinner, and went for walks in the late afternoon with their teacher Franz Adam to Café Tambosi in Odeonsplatz to smoke and to play billiards. “In the evenings we go our separate ways” Juliusz Kossak recalled of his time in Munich in 1868/69, “some to draw in the academy, others to go home for dinner or tea, most go to Brandt’s atelier where the piano is put to work, Gierymski plays, Brandt sings and Redlich is teased.”[54] The “Album of Polish Painters/Album malarzy polskich” was compiled n Brandt’s atelier at Schwanthalerstraße 19 in 1876,[55] the aim of which was to disseminate the art of the Munich group. The album contains reproductions and descriptions of works by Brandt, Chełmiński, (Wierusz-)Kowalski, Kozakiewicz, Ludwik Kurella (1834-1902)[56], Piątkowski, Streitt, Aleksander Świeszewski (1839-1895), Szerner and Roman Szwoynicki (1845-1915) and was published in the same year by Józef Unger’s publishing house in Warsaw. (see PDF)

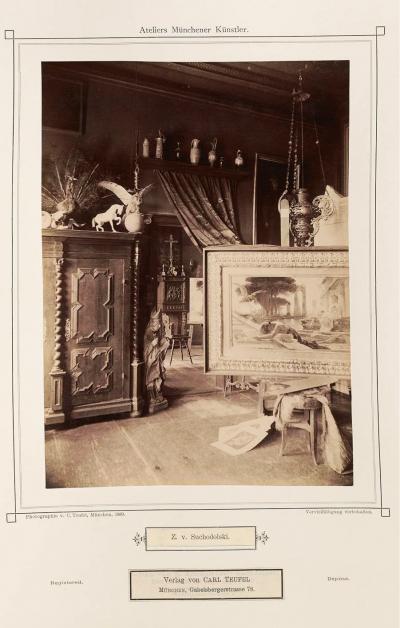

When Brandt married Helena Pruszak in 1877, who brought two children into the marriage, some of their social life moved to the couple’s apartment, where they also had two daughters together. One of the godfathers was Prince Luitpold of Bavaria. The family lived in the first floor of an apartment block in Barerstraße in Maxvorstadt with a view of the Neue Pinakothek[57] and had an open house where friends and acquaintances from the Polish artist colony and Munich society were welcome guests. In his atelier in Schwanthalerstraße, Szerner allowed visitors in for viewings. The Polish artist Anna Bilińska (1857-1893) wrote about visiting the atelier when she travelled to Munich in 1882: Brandt hadn’t been present for ages, but Szerner allowed her and her companions to visit the rooms. Szerner’s stiffness virtually made her freeze, “mrozi nasz stywność jakas.”[58] The fact that Brandt did not neglect his museum-like atelier even over the course of many years is documented by the photographs taken by Teufel in 1889.

[49] Langer 1992, page 56

[50] Doris H. Lehmann: Künstlerfeste, in: Malerfürsten 2018, page 233-235

[51] Bagińska 2015, page 45

[52] Langer 1992, page 56 f.

[53] Detailed biographies of the most notable Polish artists in Munich can be found in this portal via the link list “Münchner Schule 1828-1914”, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/lexikon/muenchner-schule-1828-1914

[54] Ptaszyńska 2008, page XIII

[55] Bagińska 2015, page 45

[56] Detailed biography in the Encyclopaedia Polonica, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/lexikon/kurella-ludwik

[57] Munich address book for 1885, Part I, page 58: “Brandt, Jos. v. k. Prof. Historien- u. Schlachtenmal. Ehrenmitgl. d. Akadem. Barerstr. 31/1.”

[58] Bagińska 2015, page 44