Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890

Mediathek Sorted

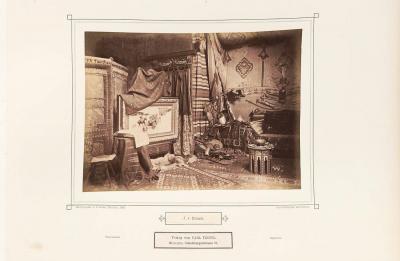

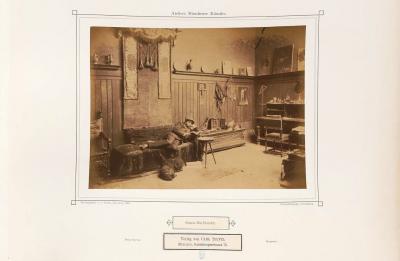

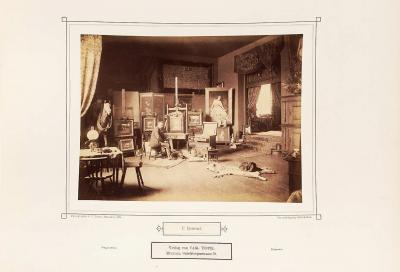

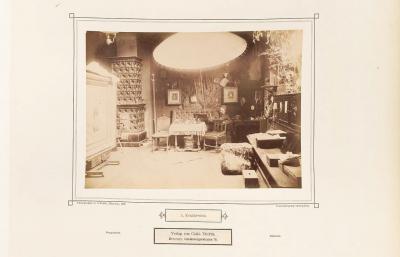

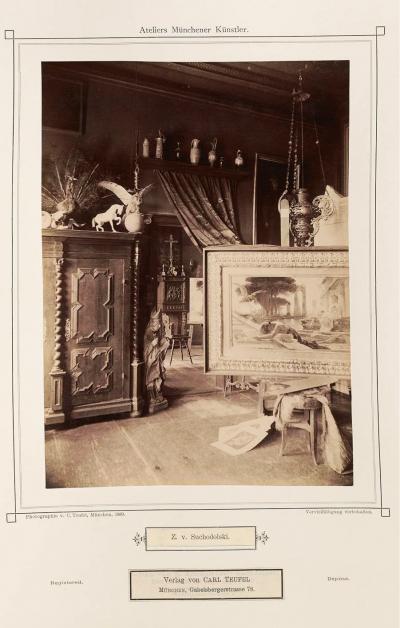

After Teufel’s death, these negatives arrived via a number of different stops at the publisher Benno-Filser Verlag in Augsburg, who gave them as part of its archive of 22,500 negatives to the Bildarchiv Foto Marburg image archive in 1935, where they can still be found today.[6] These negatives also include the same, different or completely new images of the ateliers of Polish artists, again including Brandt (Fig. 1), Buchbinder (Fig. 3), Czachórski (Fig. 5) and Ejsmond (Fig. 7, 8), then Zdzisław Jasiński (Fig. 10), Kozakiewicz (Fig. 11), Kazimierz Pułaski (Fig. 13), Rosen (Fig. 14), Streitt (Fig. 16), Suchodolski (Fig. 18) and Wierusz-Kowalski (Fig. 20, 21). The Polish artists were not always identified correctly by the archive or in the literature, which can, in part, be ascribed to the German name variations which were in use in Munich and with which the photos and negatives were labelled. This is the case with Franciszek Streitt[7] and Kazimierz Pułaski[8], for example.

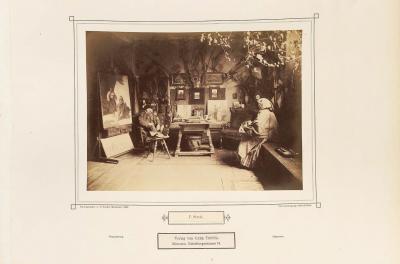

Teufel’s photographs constitute the most extensive and best researched documenting of this particular form of artist atelier during the Historism period.[9] Contemporaries, such as Beck, recognised that the ateliers were not all furnished the same reflecting the tastes of the time, but instead the way they were fitted out differed depending on the painters’ own perspective of their artistic work. They mainly differed in terms of the artistic fields favoured by the artists using them, for example, whether they were landscape, portrait, genre, historical, military, hunting or equestrian painters or whether they dealt with religious, symbolist or oriental subjects. What is more, their success as an artist and thus their financial situation naturally had an impact on the size of the rooms and the opulence and quality of the furnishings.

Beck, who had obviously selected artists who he knew personally or whose work he knew from exhibitions, wrote: “I would like to call the atelier’s furnishings the visible characterisation of the artistic individual.”[10] In the atelier of the famous Munich portrait artist Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904), who had had a stately villa built between 1886 and 1889, Beck saw “soft sumptuous carpets on the floor; even more sumptuous giant tapestries on the walls. In one corner a stepped structure was occupied by art treasures that were few in number but valuable – otherwise there were none of those odds and ends that lend a room charm – everything here exudes classic calm.”[11] When he visited the military painter Louis Braun’s atelier (1836-1916), Beck discovered his collection of weapons: “the requisites of the soldier strewn around or piled up, in colourful chaos, like that served up by the battlefield itself”, as well as a model fortress, presumably made from plaster and wood, as an object for study.[12] At Edmund Harburger’s (1846-1906), painter of humorist peasant scenes, Beck discovered a lifelike rustic living room.[13] The portrait artist Rudolf Wimmer (1849-1915) astonished guests with a room “furnished for the most noble visitors, everywhere we look we encounter fine artistic taste in serious grandeur”.[14] At Karl Raupp’s (1837-1918) atelier, who painted the lives of the fishermen and country folk on Chiemsee, a fishing boat that had been cut in half rested on an elegant, silk-covered stool in the middle of renaissance furniture with busts and ornamental plates. The portrait and society painter Georg Papperitz (1846-1918), who was a “man of fashionable society”,[15] had arranged his sketches and framed paintings in a high, wide room with three round arches and classical fluted columns, whilst at Walther Firle’s (1859-1929), who painted religious genre scenes, a stuffed crane on the ceiling floated over a “primitive altar, candelabras and church requisites”[16].

[6] Langer 1992, page 9 f.; 346 images are on the Image Index of Art and Architecture website, https://www.bildindex.de/, and can be retrieved alphabetically according to the artists portrayed using the search term “Münchner Künstlerateliers”. Information on the origins of the images can be found on most pages via the link “More information on the Filser photo bundle 1935”.

[7] Teufel 1889, Volume 3, plate 82 (“F. Streit”, see Fig. 17); Bildindex Foto Marburg (“Franz Streit”), https://www.bildindex.de/media/obj22005152/fm121835

[8] Langer 1992, page 176 (“Casimir von Pulaski, unknown”); Bildindex Foto Marburg (“K. von Pulaski, still-life artist”), https://www.bildindex.de/media/obj22005106/fm121771

[9] Compare in particular the dissertation by Brigitte Langer 1992 on this subject (see literature).

[10] Beck 1890, column 232

[11] Beck 1890, column 235

[12] Beck 1890, column 248

[13] Beck 1890, column 248 f.

[14] Beck 1890, column 397

[15] Beck 1890, column 402

[16] Beck 1890, column 409