Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890

Mediathek Sorted

In the autumn of 1889, the Munich author and editor Julius Beck (1852-1920) published a two-instalment article in the popular magazine Vom Fels zum Meer, published by Wilhelm Spemann’s Union-Verlag in Stuttgart, about “Munich artists’ ateliers”. Beck’s observation’s were based on photographs of the interiors of sixty studios which were taken by Carl Teufel (1845-1912), a professional photographer from Munich, in 1889 and which also show the artists in various poses. In his essay, Beck reproduced twelve such images in the form of wood engravings, but without stating the origin of the images or the name of the photographer.[1]

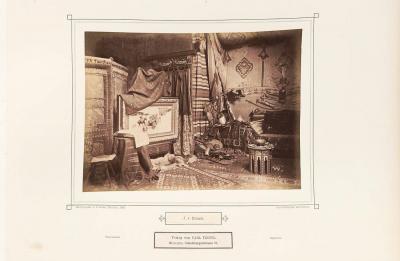

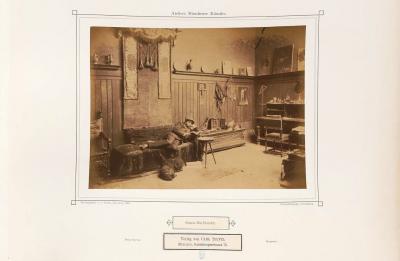

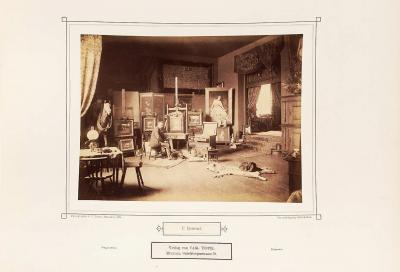

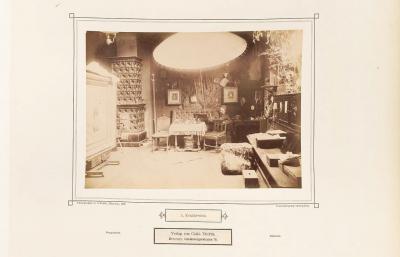

Prints of Teufel’s original images had previously been published in the Munich publishing house Ackermanns Nachfolger Emil Franke in the spring of 1889 in folio format and could be bought separately for two marks each. The art critic Friedrich Pecht (1814-1903) reported in the magazine Die Kunst für Alle: These photographs do not just show the “bird”, they also show the “nest” which they, the artists, have built from “rarities bundled together from around the world”. From the artists’ poses you can tell their “disposition”, “since the occasional smugness of those concerned, just like the amiable modesty, proved almost consistently to be much more titillating and much more creative” than most portrait painters would have wanted to portray.[2] Beck wrote about the effect the artists’ ateliers had on the audience: “Atelier! How strange this foreign word seems to me, not native at all, and yet so homelike, so meaningless in the generality of the present day and yet so meaningful as a speciality […] For the room in which the academic, the poet, the author, the composer creates, we have the expressive ‘workroom’, the ‘study room’; the artist has - an atelier! – What magic can be found in the word alone. How much it invigorates our curiosity, and how active our imagination becomes when we try to make the term cohesive with the person and the works of the artist.”[3]

From the beginning of the 1870s right up to the turn of the century and beyond, artists’ ateliers, especially those of painters – among the photographs taken by Teufel are five images of sculptors’ workshops[4] – were not just used as workshops for producing artworks. Instead, they were richly decorated reception rooms in which the artists received their students, fellow painters, collectors and gallery owners, high-ranking bigwigs and travellers from all over the world. Their role model was the atelier of the Viennese historic painter Hans Makart (1840-1884), who set up a new painting studio in Vienna after his return from Rome in 1872 and lavishly decorated it with heavy wall hangings, elaborately carved furniture, carpets, brass instruments, antiques, weapons and enormous bouquets of dried flowers, emu feathers and palm branches. Makart held his atelier parties there, received the Austrian Empress Elisabeth and allowed tourist groups to visit in the afternoons. In the twenty to thirty years that followed, up to three hundred prestigious artists’ ateliers, some open to the public, were established, predominantly in Munich where Makart had studied from 1860 under the historic painter Carl Theodor von Piloty (1826-1886).

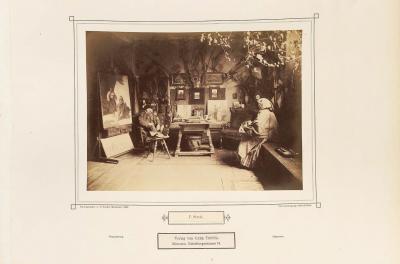

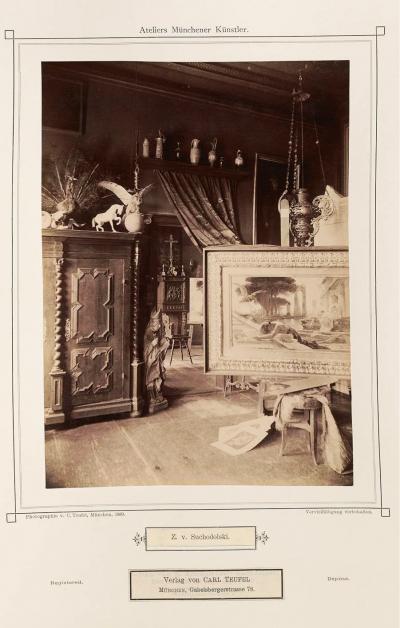

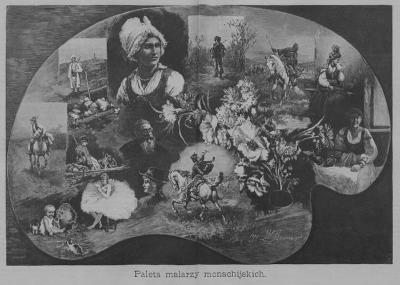

Moreover, in 1889 Teufel self-published a three-volume print edition, each containing one hundred prints of his atelier images.[5] They also include nine photographic images of the studios of Polish artists who lived in Munich for a few years or until the end of their life, including images by Józef Brandt (Fig. 2), Szymon Buchbinder (Fig. 4), Władysław Czachórski (Fig. 6), Franciszek Ejsmond (Fig. 9), Antoni Kozakiewicz (Fig. 12), Jan Rosen (Fig. 15), Franciszek Streitt (Fig. 17), Zdzisław Suchodolski (Fig. 19) and Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski (Fig. 22). However, Teufel, whose main profession involved producing template photographs for artists, which included landscapes, scenes from the world of work, historical architecture and nudes, and thousands of documentary images for the Bavarian National Museum and the Bavarian State Library, took a lot more photographs in the artists’ ateliers. Today, we know of about 375 motifs from 237 Munich ateliers which he photographed from 1889/90 up until the end of his life, around 340 original glass negatives of which have remained intact in a 14 x 18 cm format.

[1] A selection of the images used by Beck as well as assumptions and stimuli from his article can be found a little later in the article “Painter’s Studios” by Lewis C. Hind in: The Art Journal, New Series, London 1890, pages 11-16 and 40-45, a sequel of which was dedicated to the studios of English artists (pages 135-139) (digital reproduction: https://archive.org/details/gri_33125006187625/page/n23). All links in the following notes were last retrieved in December 2018.

[2] F. Pt. (Friedrich Pecht): “So wenig man ein Mädchen kennt …“, in: Die Kunst für Alle, 4th Edition 1888/89 (Issue 18, 15 June 1889), Munich 1889, page 288 (digital reproduction: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kfa1888_1889/0369/image)

[3] Beck 1890 (see Literature), column 229 f.

[4] Langer 1992 (see Literature), page 10

[5] Teufel 1889, 3 volumes (see literature and online resources)