Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890

Mediathek Sorted

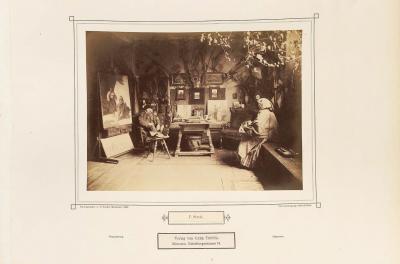

Like Makart in Vienna, Brandt did not just use his atelier to receive members of the royal family, he also held parties there. In 1876, he celebrated his name day in the atelier with his circle of artist friends. Szerner and Brandt’s student Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz (1852-1916) gave him flowers, antiquities and presents he had made himself. The rooms were full of people, reported Brandt in a letter to his mother in Poland “everyone from the whole Adam family right up to the youngest Polish generation was at my place so that it actually became quite embarrassing”.[41] On the following Monday, Prince Luitpold congratulated him in person. Brandt’s atelier was at the heart of the social scene, as was the case with Lenbach, Kaulbach and many other Munich artists. In the eyes of the public, the monarch’s visit turned painters and sculptors into “painter princes”.[42] The “painter prince” Piloty, wrote the art critic Friedrich Pecht (1814-1903), like Makart after him, is one of those artists who delight in the company of the great”.[43] Since his appointment as Prince Regent in 1886, Luitpold had continued to encourage the aristocratic image of the artists by elevating artists to professorships and to the nobility in an almost exaggerated way.[44] Brandt, who came from a well-to-do family of the minor Polish nobility, married Helena von Woyciechowski Pruszak/z Woyciechowska Pruszakowa in 1877. As a result, he became the owner of the Orońsko estate and a representative of the House of Lords in the Russian ruled Congress Poland, where he organised a painting academy during the summer months with other painters from the Polish artist colony in Munich. In 1878, he was appointed honorary professor of the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and in 1898 was awarded the Bavarian Order of Maximilian for Science and Art.

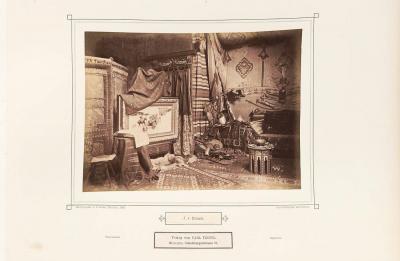

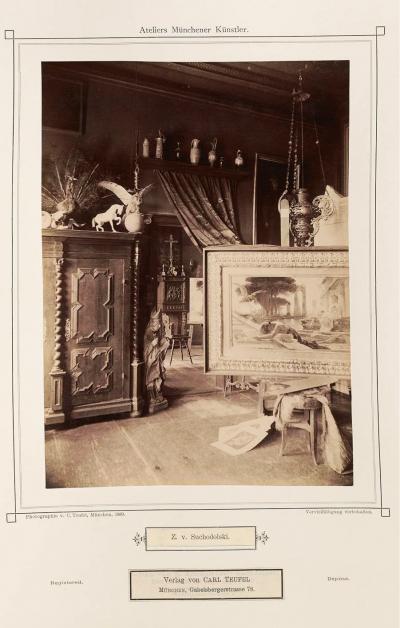

Just how much the individual objects from Brandt’s historical collection, which are now in museums, actually served as models for his paintings, cannot really be proven. His interest in motifs of the 17th century, that is to say the era of the Polish wars, does indeed coincide with the main focus of his collection. In the decade between 1863 and 1873, he painted battle paintings that spanned the whole of the 17th century, some of which were big enough to fill entire walls: 1863 - the “March of the Lisowskis” with a scene from the Polish-Ottoman war 1620/21, 1867 - the “Battle of Chocim” from 1621, 1870 - the winter scene “Czarniecki in the battle of Kolding” from the Second Nordic War in 1658, 1873 - a monumental scene from the “Battle of Vienna”, in which in September 1683 the Turks fled from the onslaught of the Polish hussars leaving their tents behind.[45] Objects in the collection, a large number of which Wankie dated to the 17th century and which glistened and sparkled from all the gold, corresponded to these; but Brandt also owned artefacts from the time of Sigismund II Augustus (1520-1572) and the Bar Confederation (1768-72).[46]

Visitors could easily find a link between the Turkish tents in Brandt’s atelier and the painting “The Battle of Vienna”, which was exhibited at the Vienna World Exhibition 1873 and then in the Munich Art Association and which rave reviews of the time even compared to works by Makart.[47] Conversely, you would be hard pressed to find the contemporary weapons, armour and harnesses from Brandt’s collection in the seething mass of people in the battle paintings. However, Polish museums have numerous in-depth studies of armour, weapons, saddles, costumes and whole figures which were produced by the artist and which he presumably used as templates for his paintings. Over time he developed a greater predeliction for small-format genre and riding scenes, which were created in large numbers in the context of his battle paintings and in which picturesque costumes and requisites played an important role, such as in the paintings produced around 1880 “Zaporozhsky encampment” and “March with spoils of war”.[48]

[41] Daszewski 1985 (see note 39), page 60, 62; Bagińska 2005, page 45; Ptaszyńska 2008, page XIV

[42] Langer 1992, page 51, 66

[43] Pecht 1880 (see note 21), page 651

[44] Jooss 2012, page 159 f.

[45] In the online exhibition “Józef Brandt” in this portal, Fig. 6, 9, 14, 17, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/Atlas-der-Erinnerungsorte/jozef-brandt

[46] Bagińska 2015, page 46

[47] see note 24

[48] In the online exhibition “Józef Brandt” in this portal, Fig. 29, 31, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/Atlas-der-Erinnerungsorte/jozef-brandt