Ateliers of Polish painters in Munich ca. 1890

Mediathek Sorted

In the autumn of 1889, the Munich author and editor Julius Beck (1852-1920) published a two-instalment article in the popular magazine Vom Fels zum Meer, published by Wilhelm Spemann’s Union-Verlag in Stuttgart, about “Munich artists’ ateliers”. Beck’s observation’s were based on photographs of the interiors of sixty studios which were taken by Carl Teufel (1845-1912), a professional photographer from Munich, in 1889 and which also show the artists in various poses. In his essay, Beck reproduced twelve such images in the form of wood engravings, but without stating the origin of the images or the name of the photographer.[1]

Prints of Teufel’s original images had previously been published in the Munich publishing house Ackermanns Nachfolger Emil Franke in the spring of 1889 in folio format and could be bought separately for two marks each. The art critic Friedrich Pecht (1814-1903) reported in the magazine Die Kunst für Alle: These photographs do not just show the “bird”, they also show the “nest” which they, the artists, have built from “rarities bundled together from around the world”. From the artists’ poses you can tell their “disposition”, “since the occasional smugness of those concerned, just like the amiable modesty, proved almost consistently to be much more titillating and much more creative” than most portrait painters would have wanted to portray.[2] Beck wrote about the effect the artists’ ateliers had on the audience: “Atelier! How strange this foreign word seems to me, not native at all, and yet so homelike, so meaningless in the generality of the present day and yet so meaningful as a speciality […] For the room in which the academic, the poet, the author, the composer creates, we have the expressive ‘workroom’, the ‘study room’; the artist has - an atelier! – What magic can be found in the word alone. How much it invigorates our curiosity, and how active our imagination becomes when we try to make the term cohesive with the person and the works of the artist.”[3]

From the beginning of the 1870s right up to the turn of the century and beyond, artists’ ateliers, especially those of painters – among the photographs taken by Teufel are five images of sculptors’ workshops[4] – were not just used as workshops for producing artworks. Instead, they were richly decorated reception rooms in which the artists received their students, fellow painters, collectors and gallery owners, high-ranking bigwigs and travellers from all over the world. Their role model was the atelier of the Viennese historic painter Hans Makart (1840-1884), who set up a new painting studio in Vienna after his return from Rome in 1872 and lavishly decorated it with heavy wall hangings, elaborately carved furniture, carpets, brass instruments, antiques, weapons and enormous bouquets of dried flowers, emu feathers and palm branches. Makart held his atelier parties there, received the Austrian Empress Elisabeth and allowed tourist groups to visit in the afternoons. In the twenty to thirty years that followed, up to three hundred prestigious artists’ ateliers, some open to the public, were established, predominantly in Munich where Makart had studied from 1860 under the historic painter Carl Theodor von Piloty (1826-1886).

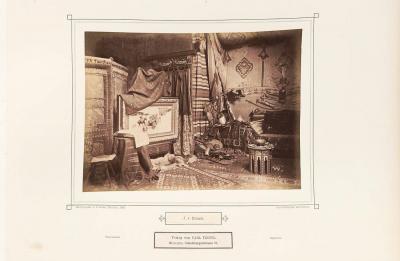

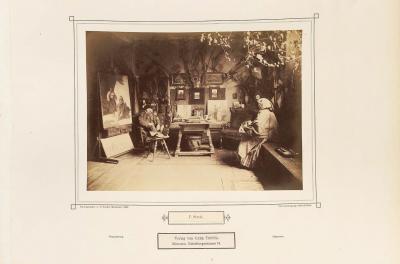

Moreover, in 1889 Teufel self-published a three-volume print edition, each containing one hundred prints of his atelier images.[5] They also include nine photographic images of the studios of Polish artists who lived in Munich for a few years or until the end of their life, including images by Józef Brandt (Fig. 2), Szymon Buchbinder (Fig. 4), Władysław Czachórski (Fig. 6), Franciszek Ejsmond (Fig. 9), Antoni Kozakiewicz (Fig. 12), Jan Rosen (Fig. 15), Franciszek Streitt (Fig. 17), Zdzisław Suchodolski (Fig. 19) and Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski (Fig. 22). However, Teufel, whose main profession involved producing template photographs for artists, which included landscapes, scenes from the world of work, historical architecture and nudes, and thousands of documentary images for the Bavarian National Museum and the Bavarian State Library, took a lot more photographs in the artists’ ateliers. Today, we know of about 375 motifs from 237 Munich ateliers which he photographed from 1889/90 up until the end of his life, around 340 original glass negatives of which have remained intact in a 14 x 18 cm format.

After Teufel’s death, these negatives arrived via a number of different stops at the publisher Benno-Filser Verlag in Augsburg, who gave them as part of its archive of 22,500 negatives to the Bildarchiv Foto Marburg image archive in 1935, where they can still be found today.[6] These negatives also include the same, different or completely new images of the ateliers of Polish artists, again including Brandt (Fig. 1), Buchbinder (Fig. 3), Czachórski (Fig. 5) and Ejsmond (Fig. 7, 8), then Zdzisław Jasiński (Fig. 10), Kozakiewicz (Fig. 11), Kazimierz Pułaski (Fig. 13), Rosen (Fig. 14), Streitt (Fig. 16), Suchodolski (Fig. 18) and Wierusz-Kowalski (Fig. 20, 21). The Polish artists were not always identified correctly by the archive or in the literature, which can, in part, be ascribed to the German name variations which were in use in Munich and with which the photos and negatives were labelled. This is the case with Franciszek Streitt[7] and Kazimierz Pułaski[8], for example.

Teufel’s photographs constitute the most extensive and best researched documenting of this particular form of artist atelier during the Historism period.[9] Contemporaries, such as Beck, recognised that the ateliers were not all furnished the same reflecting the tastes of the time, but instead the way they were fitted out differed depending on the painters’ own perspective of their artistic work. They mainly differed in terms of the artistic fields favoured by the artists using them, for example, whether they were landscape, portrait, genre, historical, military, hunting or equestrian painters or whether they dealt with religious, symbolist or oriental subjects. What is more, their success as an artist and thus their financial situation naturally had an impact on the size of the rooms and the opulence and quality of the furnishings.

Beck, who had obviously selected artists who he knew personally or whose work he knew from exhibitions, wrote: “I would like to call the atelier’s furnishings the visible characterisation of the artistic individual.”[10] In the atelier of the famous Munich portrait artist Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904), who had had a stately villa built between 1886 and 1889, Beck saw “soft sumptuous carpets on the floor; even more sumptuous giant tapestries on the walls. In one corner a stepped structure was occupied by art treasures that were few in number but valuable – otherwise there were none of those odds and ends that lend a room charm – everything here exudes classic calm.”[11] When he visited the military painter Louis Braun’s atelier (1836-1916), Beck discovered his collection of weapons: “the requisites of the soldier strewn around or piled up, in colourful chaos, like that served up by the battlefield itself”, as well as a model fortress, presumably made from plaster and wood, as an object for study.[12] At Edmund Harburger’s (1846-1906), painter of humorist peasant scenes, Beck discovered a lifelike rustic living room.[13] The portrait artist Rudolf Wimmer (1849-1915) astonished guests with a room “furnished for the most noble visitors, everywhere we look we encounter fine artistic taste in serious grandeur”.[14] At Karl Raupp’s (1837-1918) atelier, who painted the lives of the fishermen and country folk on Chiemsee, a fishing boat that had been cut in half rested on an elegant, silk-covered stool in the middle of renaissance furniture with busts and ornamental plates. The portrait and society painter Georg Papperitz (1846-1918), who was a “man of fashionable society”,[15] had arranged his sketches and framed paintings in a high, wide room with three round arches and classical fluted columns, whilst at Walther Firle’s (1859-1929), who painted religious genre scenes, a stuffed crane on the ceiling floated over a “primitive altar, candelabras and church requisites”[16].

Lenbach, also a student of Piloty, had already set up a prestigious series of three rooms in his former studio that he ran from 1871 to 1886 in the atelier building of the sculptor Anton Hess (1838-1909) at Luisenstraße 17 in Maxvorstadt[17]: Whilst the first room served as the hallway, the second contained a museum-like collection with copies of Dutch and Italian paintings on walls covered with red damask. Also on display were bronze busts, carved cabinets, majolica, bear and tiger skins and antiquities “of all genres and periods”, which the artist had gathered during his trips through Europe. Only after passing through these rooms, was it possible to reach the third actual workroom, which was kept simple.[18] During his subsequent stay in Rome, Lenbach worked on a plan to build his Munich villa “as a palace which will eclipse anything that has gone before”. His historical collections were, at the highest level, to form the framework for his own works and integrate them seamlessly into the historical development of art: “There, the powerful centres of European art are to be connected with the present.”[19]

The historic artist and portrait painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach (1850-1920) set up his atelier to have a similarly high-profile. Since 1872, he had had an apartment and atelier in an apartment building at Schwanthalerstraße 36 in Ludwigsvorstadt, the rooms of which he had obviously had furnished in a stately manner. He purchased it in 1876. In 1887-89, like Lenbach, he had a villa built in the Italian Renaissance style by the architect Gabriel von Seidl (1848-1913). Whilst Lenbach’s atelier and collection were set up in an annex, Kaulbach’s atelier rooms were in the residential building where they extended across two floors over an area of 132 square metres. At the beginning of the 1890s, the studio, with its furnishing of tapestries, oriental runners, heavy materials and draperies, a coffered wooden ceiling, carved door frames, Renaissance furniture and antique sculptures, was considered the most elegant and most magnificently furnished atelier in the whole of Munich.[20] Kaulbach displayed his own paintings standing on easels and on the parquet floor along the walls. Makart in Vienna, and Lenbach and Kaulbach in Munich, but also Frederic Leighton in England, the Polish historical painter Jan Matejko in Krakow, the Hungarian Mihály Munkáczy in Paris and a generation later Franz von Stuck, again in Munich, were considered “painter princes”, not just because of their opulent artists’ residences but also because of their close ties to the ruling and royal houses and because of public homages. “Painter prince” was an unofficial and undefined title, which was actually bestowed upon Peter Paul Rubens in earlier art history and which was also applied to other artists in the late 19th century.[21]

Sketched aspects and literary descriptions of the atelier of the Polish battle, equestrian and genre painter Józef Brandt (1841-1915), who called himself Josef von Brandt in Munich due to his heritage as Polish nobility, date back to the 1870s.[22] Brandt, who grew up in Warsaw, came to study in Munich via Paris in 1863. He was a year younger than Makart and, like Lenbach and Makart, studied at the Royal Academy of Visual Arts under Carl Theodor von Piloty, but mainly studied in the private atelier of the equestrian painter Franz Adam (1815-1886) and in the watercolour courses given by Theodor Horschelt (1829-1871). In 1867, he rented one of three interconnected atelier rooms at Franz Adam’s at Schillerstraße 23 in Ludwigsvorstadt. Adam taught his students, including the Polish painter Aleksander Gierymski (1850-1901), in the first room, the latter's brother Maksymilian Gierymski (1646-1874) and the Polish painter Juliusz Kossak (1824-1899), who was in Munich from 1868 to 1869, worked in the second, and Brandt did his work in the third.[23] In 1869, Brandt, who during his first year of study in Munich had already presented his works to the public there and in Krakow with tremendous success, completed his studies and went to work as a freelance artist.[24] In 1870, he moved into an apartment in the adjacent Landwehrstraße where one room served him as an atelier,[25] and in 1871 he moved one street further to Schillerstraße.[26] In 1874, Brandt rented a five-room apartment not far from Kaulbach on the second floor of an apartment building at Schwanthalerstraße 19, which he converted to meet his needs and in which he kept his atelier up until his death.[27] It is assumed that Prince Luitpold of Bavaria (1821-1912) visited Brandt’s atelier in this year. The Prince was known for his friendly association with the Munich art scene and for his visits to young artists, which were as regular as they were unannounced.[28] We can assume this because in autumn 1874, Brandt was invited to Luitpold’s for a meal at which he also met other members of the royal family.[29]

In the years prior to that, Brandt had collected a large number of antiques and requisites on his travels through Poland and the Ukraine, which he used as models for his painting. He also acquired such objects from other artists or from noble families in Poland who had fallen on hard times, sometimes paying for them with paintings.[30] Over time, then, he had put together an extensive collection of sabres and pistols from the Polish hussars, armour, helmets, shields, horse saddles and ‑harnesses, musical instruments and costumes with the figures that belonged to them, antique curtains and fabrics, oriental seating and tables, Turkish tents, Persian carpets and Renaissance and Baroque furniture. His new atelier in Schwanthalerstraße did not just present Brandt with the option to store these objects, he also used them to furnish and decorate his atelier prestigiously. On one side of the corridor he created two atelier rooms, the larger of which he furnished with oriental sofas, a table with inlay work, furniture from the 16th and 17th century, weapons and armour. He covered the walls with a Turkish tent, on the floor he draped Persian rugs. Easels and shelves for paints and brushes served as utensils for his painting. In the second room, he stored suits of armour and musical instruments. It is here that his friend the painter Władysław Szerner (1836-1915) worked for many years, and was also employed by Brandt as a curator for the collection.[31] On the opposite side of the corridor, he set up a storeroom for costumes, pictures and books and an arsenal of historical weapons, suits of armour, regimental banners and Turkish tents, all beautifully organised.

Soon after its opening, Brandt’s atelier was to cause a sensation, not just in Munich but in Poland as well. Obviously based on photographs, Szerner drew an aspect in which Brandt is sitting with a palette at the foot of an elaborately framed painting, which is standing on the easel, and is leafing through an illustrated book. The room was decorated with antlers, weapons, historic materials, wall hanging and draperies, statues, caddies and his own paintings. The interior aspect, that already contains all the elements of the photographs that were created about fifteen years later by Teufel, was published in the Warsaw magazine Kłosy [in English, Ears] in June 1876 as a wood engraving.[32] In October, the Polish author Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (1812-1887), who was based in Dresden, gave a detailed report in his “letters from Munich“ about Brandt’s atelier, which is “truly a historical museum”, “jest to całe muzeum historyczne”.[33] In the December, two aspects of the atelier, on a sheet signed in turn by Szerner, were published on a double page in the Warsaw magazine Tygodnik Ilustrowany [in English, Illustrated Weekly].[34] In these pictures, a second room can also be seen with draperies, an artistically decorated collection of sabres, suits of armour and regimental flags, which is crowned by a picture of the black Madonna and which inspired Szerner to create an even more extensive and decoratively adorned frame for his aspect of the atelier rooms, which was engraved in wood and gave the impression of a peep-box.[35]

The two photographs taken by Teufel in 1889, one of which appears in his book (Fig. 1, 2), show that the basic layout has not changed much in the past fifteen years. However, the collection is now grouped more closely, and carved lintels and screens, ornamental plates and numerous oriental rugs have been added. These images also appeared in Polish magazines in 1890 and 1899.[36] In 1903, the Polish painter and art critic Władysław Wankie (1860-1925), who from 1882 was part of the Munich circle around Brandt for twenty years, reported in the magazine Życie i Sztuka [Life and Art],[37] which was published in St. Petersburg, that even in Poland only a few people would have such an abundance of historical objects as Brandt, “mało kto i w kraju posiada taką całość naszych zabytków”.[38] The most extensive description of the atelier apartment in Schwanthalerstraße comes from one of Brandt’s grandsons, who, at the age of nine visited Brandt, in 1915 when he was dying, and later wrote about it.[39] In 1920, and in accordance with Brandt’s will, all of the in excess of 330 objects which constituted the furnishing of the atelier were transported to Warsaw and given to the National Museum.[40]

Like Makart in Vienna, Brandt did not just use his atelier to receive members of the royal family, he also held parties there. In 1876, he celebrated his name day in the atelier with his circle of artist friends. Szerner and Brandt’s student Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz (1852-1916) gave him flowers, antiquities and presents he had made himself. The rooms were full of people, reported Brandt in a letter to his mother in Poland “everyone from the whole Adam family right up to the youngest Polish generation was at my place so that it actually became quite embarrassing”.[41] On the following Monday, Prince Luitpold congratulated him in person. Brandt’s atelier was at the heart of the social scene, as was the case with Lenbach, Kaulbach and many other Munich artists. In the eyes of the public, the monarch’s visit turned painters and sculptors into “painter princes”.[42] The “painter prince” Piloty, wrote the art critic Friedrich Pecht (1814-1903), like Makart after him, is one of those artists who delight in the company of the great”.[43] Since his appointment as Prince Regent in 1886, Luitpold had continued to encourage the aristocratic image of the artists by elevating artists to professorships and to the nobility in an almost exaggerated way.[44] Brandt, who came from a well-to-do family of the minor Polish nobility, married Helena von Woyciechowski Pruszak/z Woyciechowska Pruszakowa in 1877. As a result, he became the owner of the Orońsko estate and a representative of the House of Lords in the Russian ruled Congress Poland, where he organised a painting academy during the summer months with other painters from the Polish artist colony in Munich. In 1878, he was appointed honorary professor of the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, and in 1898 was awarded the Bavarian Order of Maximilian for Science and Art.

Just how much the individual objects from Brandt’s historical collection, which are now in museums, actually served as models for his paintings, cannot really be proven. His interest in motifs of the 17th century, that is to say the era of the Polish wars, does indeed coincide with the main focus of his collection. In the decade between 1863 and 1873, he painted battle paintings that spanned the whole of the 17th century, some of which were big enough to fill entire walls: 1863 - the “March of the Lisowskis” with a scene from the Polish-Ottoman war 1620/21, 1867 - the “Battle of Chocim” from 1621, 1870 - the winter scene “Czarniecki in the battle of Kolding” from the Second Nordic War in 1658, 1873 - a monumental scene from the “Battle of Vienna”, in which in September 1683 the Turks fled from the onslaught of the Polish hussars leaving their tents behind.[45] Objects in the collection, a large number of which Wankie dated to the 17th century and which glistened and sparkled from all the gold, corresponded to these; but Brandt also owned artefacts from the time of Sigismund II Augustus (1520-1572) and the Bar Confederation (1768-72).[46]

Visitors could easily find a link between the Turkish tents in Brandt’s atelier and the painting “The Battle of Vienna”, which was exhibited at the Vienna World Exhibition 1873 and then in the Munich Art Association and which rave reviews of the time even compared to works by Makart.[47] Conversely, you would be hard pressed to find the contemporary weapons, armour and harnesses from Brandt’s collection in the seething mass of people in the battle paintings. However, Polish museums have numerous in-depth studies of armour, weapons, saddles, costumes and whole figures which were produced by the artist and which he presumably used as templates for his paintings. Over time he developed a greater predeliction for small-format genre and riding scenes, which were created in large numbers in the context of his battle paintings and in which picturesque costumes and requisites played an important role, such as in the paintings produced around 1880 “Zaporozhsky encampment” and “March with spoils of war”.[48]

The decorations in the Munich ateliers were not just aimed at the initiated local public, they were also intended for tourists, foreign collectors and potential buyers, and were a fundamental part of the artists’ business models. Lenbach opened his atelier predominantly for aristocrats travelling through, Kaulbach showed his collection of Italian Renaissance paintings at set opening times. From the end of the 1870s, Munich address books listed the addresses of the artists’ ateliers in their own category along with the specialist area of each respective painter and their opening times. Travel guides for Munich in English in the 1880s‑ and 1990s‑ specifically made reference to the atelier of the Polish battle painter von Brandt, “a particularly successful master of the exotic genre and owner of an extraordinary atelier well worth seeing”.[49] In 1876, based on the idea of the costume parties that Makart held in his atelier in Vienna and for which he provided the models for the historical costumes,[50] the Munich artists celebrated Carnival in Munich in keeping with the motto “A court festival for Karl V”, which Makart and members of the Bavarian royal family also attended. Requisities from Brandt’s atelier were used at the party, with Brandt providing a Turkish troupe with costumes, which caused a sensation.[51]

In the mid-1870s, the Munich city guides and the international press listed the artists’ ateliers as Munich tourist attractions which were not to be missed. This led to streams of visitors and caused many artists to only open their atelier upon request or to shut up shop completely.[52] Brandt’s atelier mainly served as a meeting point for the Polish artist community. His circle, spread over about fifty years, included Ludwik Kurella (in Munich 1861-97), Henryk Redlich (1863-69), Szerner (1865-1915), of course, and Ajdukiewicz (1873-75), Maksymilian (1867-74) and Aleksander Gierymski (1868-97), Stanisław Szembek (1868-71), Ludomir Benedyktowicz (1868-72), Władysław Czachórski (1868-1911), Franciszek Streitt (1871-90), Antoni Kozakiewicz (1871-1900), Henryk Piątkowski (1872-75), Jan Rosen (1872-95), Jan Chełmiński (1873-76), Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski (1873-1915), Julian Fałat (1875-81), Franciszek Ejsmond (1879-94), Bohdan Kleczyński (1882-88), Szymon Buchbinder (1883-97), Apoloniusz Kędzierski (1886-89), Olga Boznańska (1886-98) and many others.[53]

The artists all lived in the same streets in Ludwigsvorstadt and Maxvorstadt and in Schwabing. They had their painting studios at the academy, in their apartments or in rear buildings occupied only by ateliers in these streets. They studied and worked together, met for lunch or dinner, and went for walks in the late afternoon with their teacher Franz Adam to Café Tambosi in Odeonsplatz to smoke and to play billiards. “In the evenings we go our separate ways” Juliusz Kossak recalled of his time in Munich in 1868/69, “some to draw in the academy, others to go home for dinner or tea, most go to Brandt’s atelier where the piano is put to work, Gierymski plays, Brandt sings and Redlich is teased.”[54] The “Album of Polish Painters/Album malarzy polskich” was compiled n Brandt’s atelier at Schwanthalerstraße 19 in 1876,[55] the aim of which was to disseminate the art of the Munich group. The album contains reproductions and descriptions of works by Brandt, Chełmiński, (Wierusz-)Kowalski, Kozakiewicz, Ludwik Kurella (1834-1902)[56], Piątkowski, Streitt, Aleksander Świeszewski (1839-1895), Szerner and Roman Szwoynicki (1845-1915) and was published in the same year by Józef Unger’s publishing house in Warsaw. (see PDF)

When Brandt married Helena Pruszak in 1877, who brought two children into the marriage, some of their social life moved to the couple’s apartment, where they also had two daughters together. One of the godfathers was Prince Luitpold of Bavaria. The family lived in the first floor of an apartment block in Barerstraße in Maxvorstadt with a view of the Neue Pinakothek[57] and had an open house where friends and acquaintances from the Polish artist colony and Munich society were welcome guests. In his atelier in Schwanthalerstraße, Szerner allowed visitors in for viewings. The Polish artist Anna Bilińska (1857-1893) wrote about visiting the atelier when she travelled to Munich in 1882: Brandt hadn’t been present for ages, but Szerner allowed her and her companions to visit the rooms. Szerner’s stiffness virtually made her freeze, “mrozi nasz stywność jakas.”[58] The fact that Brandt did not neglect his museum-like atelier even over the course of many years is documented by the photographs taken by Teufel in 1889.

In 1873, the Polish painter Alfred Kowalski (1849-1915)[59] who had previously studied in Warsaw and Dresden, came to Munich and enrolled in October of that year in the Munich Art Academy – in the same semester as Zdzisław Ajdukiewicz, Kazimierz Alchimowicz, Chełmiński, Wojciech Kossak, Wojciech Piechowski, Szwoynicki, Włodzimierz Łoś and Aleksander Mroczkowski,[60] who began their studies either in the antiquity class or, like Kowalski, under the historic painter Sándor (Alexander von) Wagner (1838-1919). It can be assumed that Kowalski, who was registered and listed in Munich under his surname, but who signed his paintings “Wierusz-Kowalski”, a combination of the Polish family names from which various name variants were formed over time, soon contacted Brandt. In 1878, he was listed for the first time in the Munich address book as a painter on the second floor of Schwanthalerstraße 19. As well as other tenants, this house accommodated numerous apartments or ateliers of other artists, such, in 1875, as well as Brandt, the painter Rudolf Hirth (du Frênes, 1846-1916) and in the neighbouring building number 19 ½ the painter Gabriel (von) Max (1840-1915), Franz Defregger (1835-1921) and Robert Beyschlag (1838-1903),[61] in 1878, as well as Kowalski, Max and Beyschlag, the Irish painter Georg(e) Folingsby (1828-1891), whilst Brandt is temporarily not listed for reasons unknown.[62]

In the years that followed, Wierusz-Kowalski moved several times,[63] but from 1889 to 1910 he had that prestigious atelier in a rear atelier building at Landwehrstraße 79 in Ludwigsvorstadt that Teufel had photographed and also included in his book (Fig. 20-22). As with Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski’s atelier became the meeting place for artists, gallery owners and collectors, one of whom was Prince Regent Luitpold. Wierusz-Kowalski also married and lived with his wife and four children in a sophisticated apartment in Goethestraße 48,[64] in which guests, including Luitpold, were always welcome.[65] In return, Wierusz-Kowalski, just like Brandt, Rosen, Ejsmond, Czachórski and others, were occasionally invited to festive dinners and receptions at the royal residence.[66] Ateliers and apartments, particularly those of Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski, did not just provide the setting for the social gatherings of the Polish artist colony, they also formed a little piece of home for the more of less voluntary exiles where they could spend time together, celebrate the Polish way of life, collaborate on activities and participation in exhibitions in Munich, Poland or abroad, get embroiled in endless political discussions and subscribe together to Polish magazines.[67]

Munich attracted foreign students because of its high-profile public art collections, the excellent training at the art academy, the aggressive promotion of the arts by the royal family and the liberal attitude of the people living there. But many Poles came to Munich, particularly after the January Uprising 1863/64 against the Russian partitioning power, as refugees or as a result of the subsequent years of repression, such as the closing of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts/Akademia Sztuk Pięknych. Between 1824 and 1914, around 700 Polish artists, sculptors and architects passed through the Munich artists’ circle, with 322 studying art officially.[68] In their day, Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski helped the new arrivals financially and provided accommodation, but they also gave them access to their rich pool of requisites in their ateliers.[69] The art critics also saw the Poles as a closed group who “ultimately became a formal school”; this is because their compositions have in common “a certain melancholic characteristic” and the “colour mood”, wrote Friedrich Pecht 1888: “Mostly they pay tribute to the true and faithful love for their homeland and their ... mixture of bleak woods, naked plains and snow which seem charming to us.”[70]

Wierusz-Kowalski, whose paintings initially followed the style of Brandt’s genre, equestrian and military scenes, followed by the hunting motifs of Maksymilian Gierymski, also used requisites from the pool in Brandt’s atelier for his subsequent riding motifs from the Caucasus and scenes from the January Uprising. From the beginning of the 1880s‑, he became known for winter scenes of wolf hunts and for coach and sled rids and portrayed, in particular, the pleasures of the Polish landed gentry on hunting trips and returning from the market. His atelier in Landwehrstraße was distinguished and furnished only with select historical pieces of furniture, oriental carpets and wall hangings. It was not a museum like Brandt’s atelier, instead, as well as being used for his art work, it was used as a place of representation, similar to the architecturally organised salon atelier of the portrait painter Papperitz, who resided only a few houses further along at Landwehrstraße 73. Only a Polish sled, which can be seen in the background on one of Teufel’s images (Fig. 22), relates to the painter’s art work and recalls the fishing boat that stood in Raupp’s atelier.

At over five metres high, the ceiling allowed the artist to paint paintings that were wall height, like the dramatic paining showing the attack by a pack of wolves on a team of horses, which Teufel had photographed whilst it was being painted in 1889 (Fig. 20). Only twenty years later, in May 1910, did Wierusz-Kowalski dare to exhibit the 5 x 10 metre large picture, which he showed in the Alten Rathaus in Munich’s Marienplatz. Prince Regent Luitpold and his family went to see the painting which, however, was largely overlooked by the public, presumably because it was no longer contemporary.[71] A reproduction was created as a wood engraving in the same year (Fig. 20a); the oil painting was destroyed by fire in 1920.[72] At the right-hand edge of Teufel’s image, an easel can be seen upon which is the painting “Team of horses crossing a ford”, which is now in the District Museum/Muzeum Okręgowe in Suwałki on loan from a private collection (Fig. 20b). Still to be definitively identified is the portrait of a hunter at the right-hand edge of Teufel’s second photograph (Fig. 21), which, when compared with a contemporary photograph, could be a portrait of Prince Regent Luitpold[73] or a picture of the Bavarian culture minister Freiherr Johann von Lutz (1826-1890), who Wierusz-Kowalski had previously portrayed on a painting that he gave to the Neue Pinakothek[74] and which today is missing.[75]

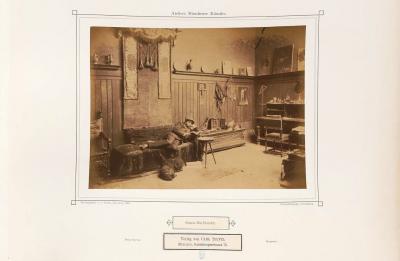

In 1871, even before Wierusz-Kowalski, Antoni Kozakiewicz (1841-1929) and Franciszek Streitt (1839-1890) came to Munich with the Polish painter Aleksander Kotsis (1836-1877). All three had been involved in painting the vaults in the mission church of Stradom near Krakow in 1862/63. From 1868, Kozakiewicz and Streitt had then studied in Vienna and travelled through Austria and the Alps with Kotsis. In Munich the three of them founded a painting atelier that is listed at Mittererstraße 7 in Ludwigsvorstadt in 1878,[76] and in 1890 is listed at Adalbertstraße 49 in Maxvorstadt spread over two floors.[77] Kozakiewicz,[78] who in Munich specialised in genre images and scenes from the rural areas and small towns of Poland and only returned to Warsaw in 1899, was an active member of the art scene around Brandt, was friends with numerous other Polish painters and was a member of the Munich Art Association from the beginning. His atelier room, as Teufel photographed it (Fig. 11-12), looks less prestigious but still quite picturesque thanks to a certain untidiness, green plants, palm fronds, a large Japanese parasol and some pistols and sabres on the wall. The painter is pressing himself rather modestly into a sofa corner and reading a journal. Resting on the easel is the framed picture of a “gypsy/Cyganka” at a camp fire, which the painter repeated several times in the decade following 1900.[79] Luitpold is also said to have visited this atelier several times. Kozakiewicz is represented in the “Album of Polish Painters” from 1876 by a bourgeois scene, “Nauki Babuni/A grandmother’s teaching”, in which a young girl learns the art of spinning (see PDF).

His friend Franciszek Streitt,[80] who traded in Munich under the German version of his name Franz Streitt, can be seen in Teufel’s photograph in his small atelier room, already visibly suffering from a serious illness (Fig. 16). Born in Brody in the Ukraine in 1839, he initially studied at the Technical Academy in Lemberg and at the School of Fine Arts/Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych in Krakow under Władysław Łuszczkiewicz (1828-1900) and Jan Matejko (1838-1893). After scenes from Polish history and literature, he mostly painted genre motifs with a sentimental leaning from the everyday life of tradesmen and peasants as in the picture “Pierwsze kroki/First steps”, which appeared in the “Album of Polish Artists” (see PDF). Streitt also had close ties to the artist colony around Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski. In his atelier photo, he is sitting opposite the model of a peasant with a basket, which is presumably a dummy in a costume. The display wall is decorated with grasses, emu feathers and stuffed birds, ivy climbs from the window along the ceiling – clearly quite a common decoration which can also be seen in the atelier photograph of the German genre painter Claus Meyer (1856-1919) in neighbouring Georgenstraße[81]. Musical instruments and leather bags also acted as decoration. On a chest in portrait format is the as yet unframed picture “A flower for the hat/Kwiatek do kapelusza“, that is still known today (Fig. 16a). On the easel is the picture that he is currently working on of a young gypsy couple; the seated violin player is also used as an individual image from 1890 (Fig. 16b).

In 1888, Streitt married a Munich painter, but died on Christmas Eve 1890. The Polish author Maria Konopicka (1842-1910), who visited Munich and the ateliers of the Polish artists at the start of a European trip, wrote about the funeral: “In the final day of the old year, the painter Franciszek Streitt was buried in Munich’s northern cemetery. The funeral was sad, his colleagues and his wife, a German, followed the coffin. The coffin enclosed his frail body and his simple spirit, which also distinguished his art work. Simplicity and truth. I don’t know any painters that could express their thoughts or indeed their feelings in just a few strokes of a drawing. This is in fact always his top priority. But how he was able to express these feelings is best evidenced by his “Recruited into the army” – the painful death of a mother and of a young soldier. Once seen, you never forget it.”[82] In 1891, the Munich Art Association put on a retrospective with sixty of the artist's works.

In 1872, Jan Rosen (1854-1936)[83] came to Munich to study after first taking drawing lessons in Dresden, which is where his family had fled after the January Uprising in 1863. Alongside his studies at the Munich Art Academy under the historic and figure painter Alexander Strähuber (1814-1882) and the scupltor, historic and genre painter Ferdinand Barth (1842-1892), he also took private painting lessons with Brandt. Together with his fellow students at the Academy, Henryk Piątkowski (1853-1932),[84] who was represented four years later in the “Album of Polish Painters” by the ancient scene “Rzymianka w kąpieli/Roman lady in the bath” (see PDF), published the Polish student magazine Kolega, and was also active in the student body and the Polish artist colony, and organised choirs and concerts. From 1874, he continued his studies in Paris, and then travelled in Poland before living in Munich again from 1883. From 1888, he had his atelier not far from Brandt at Schwanthalerstraße 32 in the rear building.[85] Under Brandt’s influence, he painted hunting motifs, equestrian scenes and portraits of people on horseback, but became famous for his battle paintings covering the Napoleonic wars and the November Uprising of 1830/31. Wanting to portray every detail as authentically as possible, he did not just study historical sources and literature, instead, following Brandt’s example, he put together a collection of pistols, sabres, uniforms, armour and helmets, model cannons, trumpets and hunting horns, which he lined up meticulously in his atelier (Fig. 14, 15). There was obviously no space for prestigious furniture, so carpets and a few wall hangings were the only things creating a homely atmosphere. Rosen too, who in Teufel’s photograph is sitting in ‘lost profile’ at his easel, appears rather reserved and unassuming.

A report by the painter, presumably from the middle of the nineties, provides an animated impression of the Prince Regent’s relationship with the Munich artists: “I am painting doggedly in my empty atelier, when there’s a ring at the door and a dashing officer comes in. He introduces himself as an adjutant of Prince Regent Luitpold and reports that his Royal Highness wishes to see my work and is waiting downstairs. Of course, I ran downstairs and showed the old gentleman in politely, who, as I found out later, saw it as his duty to visit the ateliers of artists living in his capital. And so he climbed up to my atelier, looked round, asked questions, as is good form, and then he offered me a cigar […] A few days later, an invitation to visit the Prince Regent came fluttering in like a bolt from the blue. […] I threw on the mandatory gala apparel and hurried to the meal, at five in the afternoon! I and another delinquent Czachórsk were received in a magnificent hall by the adjutant I had already met and ladies-in-waiting of Princess Therese, the daughter of Prince Regent Luitpold. After some time, our old gentleman appeared […] and escorted said Therese, a withered and non-descript spinster […]. Later, the door was opened with a bang and we were asked to take a seat at the dinner table. […] The meal was refined and good, but went on for a very long time and the conversation didn’t really want to get going.”[86] In 1895, Rosen went to Paris then lived for several years in Lausanne, Warsaw, Italy and Lwów.

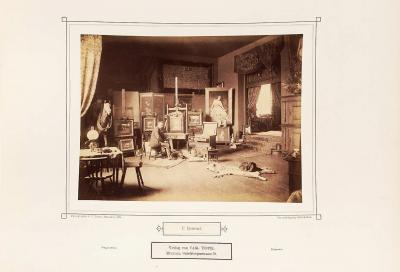

Władysław Czachórski (1850-1911)[87], known in Munich as Ladislaus von Czachorski, came to Munich in October 1869 after a few semesters in the Warsaw Drawing Class/Klasie Rysunkowej, which was founded in 1865 after the Art Academy had been closed at the decree of the Russian authorities, and at the Dresden Art Academy. He studied in Munich until 1874 under Piloty, Wagner and Hermann Anschütz (1802-1880). As Piątkowski reported, Czachórski, who he presumably already knew from the Warsaw Drawing Class, came from a noble family of landowners in Lublin.[88] In 1872, Czachórski wrote to his parents, who had obviously not been informed of his taking the step of settling in Munich as an artist, about his first atelier: “I found a quiet companion, an extraordinarily hardworking and punctual man, N. Iwanowski (a married Lithuanian), who likes to get involved. So, for that reason, we rented a really spacious atelier together for three months […] for 8 fl. [guilders], which will cost me 12 fl. We intend to paint for 4 or 3 hours a day, which together with the rooms will cost us about 16 fl. each month. I fear and appeal to you Father and Mother that you will not be angry with me for having taken such an audacious step without your permission.”[89] But the young artist was successful. His trusting and relationship with Piloty was not the only one; the “old Kaulbach”, which referred to the Director of the Art Academy, Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874), even bought a sketch from an exhibition for his collection. He wrote about it to his parents: “Even if the financial benefit isn’t great, the moral benefit is significant. This is because Kaulbach only accepts the best sketches every couple of years or so and the skinflint has a set price for them”.[90]

Czachórski went travelling for a few years through France and Italy from 1874. In 1879, he again established his own atelier in Munich, which is listed from the mid-1880s at Schillerstraße 26 in Ludwigsvorstadt on the second floor of a rear building completely occupied by artists’ ateliers.[91] He became an honorary member of the Art Academy in 1890, and in 1893 was awarded the Bavarian Order of St Michael. In the same year, Luitpold acquired his painting “The Reader” for his collection. Czachórski stayed in Munich until the end of his life. He painted scenes from literature, history and drama. However, he enjoyed his greatest success with naturalistic paintings of women in costumes and 18th century interiors portrayed in detail in which he was able to masterfully reproduce fabrics, flowers and jewellery. As a portrait painter of the Munich bourgeoisie, he won widespread recognition. His atelier, of which Teufel only photographed a small section (Fig. 5, 6), nevertheless gives some idea of the prestigious luxury of the well-to-do portrait painter who had at his disposal architecturally lavish wall panellings, brocade wallpaper, tapestries, carpets and a Japanese screen, as can also be seen in Wierusz-Kowalski’s atelier (Fig. 21). The baroque chair and the opulent ornate bronze vases appear in a similar form in his paintings of boudoirs lavishly decorated with flowers (Fig. 5a). The piano is not just an indication of the social evenings held by the Polish artist colony, similar to those of Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski, it is also a sign of an extensive cultural education.

In his atelier, Franciszek or Franz von Ejsmond (1859-1831)[92] also showcased himself as being well established and bourgeois (Fig. 7-9). From 1888 until he left Munich in 1894, he rented his atelier in the atelier building at Theresienstraße 148 in Maxvorstadt on the left of the first floor of the second rear building[93] where he also lived (Fig. 7-9). The work room, where his paintings were lined up and where he was photographed at the easel and leafing through a folder, quietly and without really posing, was high and spacious. The only decorations were created by a few Makart bouquets, coverings, wall hangings and curtains, and, here as well, a Japanese screen. Two breastplates, a stuffed bird, a shelf with vases and bottles give the impression that it was mandatory to have these kinds of requisites as well. There would have been no indication of the type of paintings Ejsmond specialised in or the subjects that were typical for him, had it not been for the life-size wooden horse with bridle and a dummy clothed like a rider which seems to run into the atelier room from the left behind a curtain (Fig. 8). Neither prestigious grandeur nor a museum-like collector’s passion characterise this painter. Steps led to the obviously cosier private rooms that were furnished with carpets, curtains, drapes and small pieces of furniture.

Ejsmond too was of noble descent, the son of a large landowner from near Radom. He initially studied in Warsaw in the private atelier of Wojciech Gerson (1831-1901) and in the Drawing Class/Klasie Rysunkowej under Aleksandr Kamiński (1823-1886) before leaving for Munich in 1879. Until 1886, he studied at the Art Academy under Wagner and under the Hungarian Piloty student and historic painter Gyula Benczúr (1844-1920). He had amicable relationships with Fałat and Brandt. In his paintings, he worked on a wide variety of themes. As well as motifs of people on horseback and snowy hunting scenes based on the model of Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski, as can be seen on one of the atelier photos (Fig. 7), he also painted figure paintings in the oriental style, portraits, still lifes, flower pieces and religious scenes. He became known, however, for his small-format genre motifs of village and small-town life, which were influenced by Düsseldorf and Munich painters, such as Knaus, Vautier, Harburger and Defregger. His sentimental and humorous scenes idealising domestic bliss and childhood were popular. One such picture, “The Firstborn/Pierworodny”, can be seen in the centre of one of the atelier photographs (Fig. 8) to the right of the large easel and was also distributed as an art postcard by the Munich publishing house owned by Franz Hanfstaengl (Fig. 8a). Versions of this motif can still be found today on the Polish auction market.[94] Next to it on the right, in front of an oven, is a large-format “odalisque” or “gypsy” positioned in the oriental style, which is similar in its stance and headdress to the motif of a painted palette by Ejsmond in the Warsaw National Museum/Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie (Fig. 8b). Whilst other Munich painters, such as Harburger, constructed entire peasant living rooms as study objects,[95] Ejsmond, after he returned to Poland, purchased a farmhouse with furniture and equipment in Dąbrówka near Grodzisk. The farmhouse served as his atelier and housed his collection of models for his paintings.

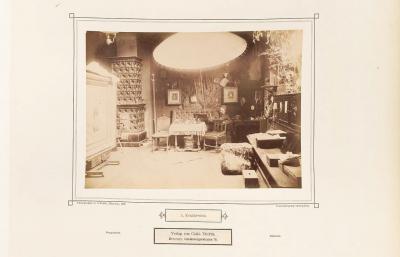

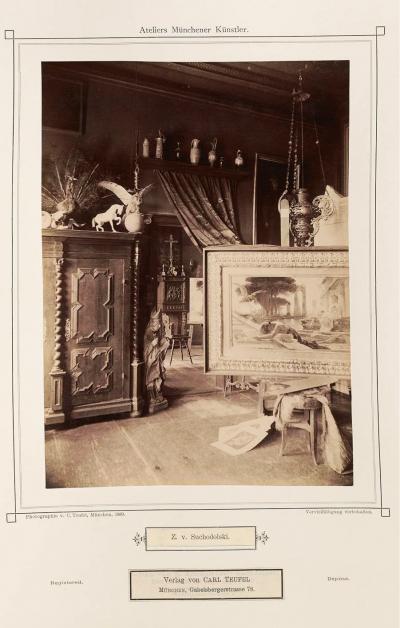

When Zdzisław (von) Suchodolski (1835-1908)[96] came to Munich in 1880, he already had most of his artistic career behind him. The son of a military painter, he initially studied law in Krakow and received his first painting lessons from his father before taking up art studies in Düsseldorf. After stays in Brussels and Paris, from 1863 he worked as a freelance painter in Italy, settling on Capri. From 1874 he lived in Weimar, where he married the painter Elisabeth von Bauer, a student of the historic painter Ferdinand Pauwels (1830-1904), and they had a son. After moving to Munich, the family lived on the third floor of Türkenstraße 98 in Maxvorstadt. His atelier was round the corner at Georgenstraße 1, where Suchodolski traded as a historical painter.[97] When the apartment under theirs became free in Türkenstraße, the family moved in and used the apartment on the top floor as their atelier.[98] The photograph of Teufel, which only shows a small section of the atelier rooms (Fig. 18, 19), hints at an upper-class, well established painter. We see a high room decorated with a classical stucco ceiling, baroque furniture, a portrait of his fifteen-year-old son Zygmunt and several ceramic bottles and jugs.

Suchodolski was not actually a historical painter. Pecht describes him as a “painter of hunting scenes distinguished, in particular, by the fine atmosphere of his pictures”.[99] However, since his time at the Düsseldorf Academy, followed by Italy and then Munich, he devoted himself in particular to religious themes, such as “Saint Cecilia teaches an angel to play the organ/Św. Cecylia ucząca aniołka gry na organach” (1857), “The Judas kiss/Pocałunek Judasza” (1859), “Most Blessed Virgin /Najświętszą Pannę” (1863), “Mother of God/Matkę Boską” (1865), “The vision of Saint Theresa/Wizja św. Teresy” (1876) or “The Three Maji/Trzej królowie” (1903). In his atelier, the effigy of a bishop or saint in the doorway and the home altar in the room behind it are clear indications of the field of painting he specialised in. The painting presented on the easel shows a previously unknown, obviously ancient theme in which a youth has fallen asleep over some writings and papers. The bird shown on the painting bears a remarkable resemblance to the stuffed owl on the Baroque cupboard. Because it is sitting on a globe, the owl could also be the heraldic animal of the Munich Schlaraffia-Vereinigung formed in Neuturmstraße in Munich’s old town in 1880 to cultivate friendship, art and humour. In 1890, the year after Teufel took his photograph, Suchodolski took part in the second Munich Annual Exhibition of Artworks from all Nations in the Glaspalast with his painting “The dreamer”,[100] and in 1893 with an oil painting entitled “Holy Family”.[101] In 1895, his wife, using the name Elisabeth von Suchodolska, exhibited a picture there called “Star Money”, whilst he showed an oil painting entitled “Idyll”.[102] The family remained in Munich. Suchodolski died there in 1908. His son Siegmund von Suchodolski (1875-1935) studied at the School of Arts and Crafts and at the Technical University and worked as an architect, commercial artist and illustrator in Munich.

When Szymon or Simeon or Simon Buchbinder (1853-1908?)[103] came to Munich in 1883, he already had many years of completed art studies and extensive professional experience behind him. From 1869, he studied in the Warsaw Drawing Class/Klasie Rysunkowej under Gerson, Kamiński and Rafał Hadziewicz (1803-1883), he then worked as a decorative painter at the Court Opera in Vienna where he continued his studies at the Art Academy. From 1879 to 1882, he completed a Masters course under Matejko at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts/Akademia Sztuk Pięknych. Whilst his older brother Józef (1839-1909)[104], who was also a painter, only spent two semesters in Dresden and Munich from 1862 to 1863, Szymon stayed in Munich for fourteen years. The brothers hailed from a Jewish family from the Lublin region. Whilst Józef was baptised under the influence of the Abbey of St Bernard in Łuków, who paid for his artistic training, and turned his hand to Christian motifs and altar painting in Rome and later in Warsaw, Szymon, under the influence of Matejko initially worked on historical themes and then focused on genre motifs from everyday Jewish life. In the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, he studied the Dutch masters of the 17th c,entury (Pecht names Frans van Mieris the Elder and Caspar Netscher)[105] and, whilst in the Bavarian capital, mostly created small-format pictures of figures and interiors in the style of the Dutch Baroque, painting fine art reminiscent of the Old Masters.

Initially residing in Goethestraße, his atelier, as photographed by Teufel (Fig. 3, 4), was at Schwanthalerhöhe 10 in Ludwigsvorstadt on the fourth floor, his private apartment not far from there at Schwanthalerstraße 35 which still bears the same name today.[106] The spacious atelier appears to be a simple work room in which the photographer for want of other decorative motifs draped the mahlstick and some books in the foreground and posed the artist with a palette and brushes. The few objects that served to furnish the atelier were a grandiose curtain, cans and ornamental plates carefully but lovelessly lined up on the mantelpiece, a Renaissance chest that almost all artists seemed to have, and a few musical instruments. Buchbinder was successful artistically and commercially. Along with the other Polish artists, he exhibited his work in the Munich Art Association. His works were talked about positively in the press and he worked, possibly on appointment, for the Munich Galerie Wimmer founded in 1825, which was located at Brienner Straße 3 in the old town and sometimes had access to subsidiaries in London and New York. In 1890, the gallery sold two of his paintings to American art collectors, in 1891 it sold a picture of a young man standing in front of the easel, which only measured 41 x 24 cm, to a collector in New York for 16,000 marks.[107] In 1897, Buchbinder went to Berlin, where he evidently stayed until the end of his life.

In 1885 Zdzisław Jasiński (1863-1932) [108], a member of a Warsaw artist family, came to Munich to study after previously studying under prominent teachers at the Warsaw Drawing Class/Klasa Rysunkowa and at the School for Drawing and Painting/Szkoła Rysunku i Malarstwa in Krakow. He enrolled in the Munich Art Acedemy under the genre and landscape painter Otto Seitz (1846-1912). In the same semester, the Poles Stanisław Radziejowski (1863-1950)[109], Apoloniusz Kędzierski (1861-1939)[110], Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz (1861-1917)[111] and Feliks Cichocki Nałęcz (1861-1921)[112] began their studies either under Seitz or in the painting class given by Nikolaus Gysis (1842-1901) and the nature class given by Johann Caspar Herterich (1843-1905).[113] Jasiński also studied historic painting under Wagner until 1889. In 1888, during his studies, he showed a painting “Peddler” at the Third International Art Exhibition in the Glaspalast.[114] The year after that, he exhibited his painting “The ailing mother” at the Munich Annual Exhibition of Artworks from all Nations,[115] which can also be seen on the easel in Teufel’s atelier photograph (Fig. 10). The painting was awarded a prize at an exhibition held by the Art Academy and then became so well known that it was produced the following year in a Paris publication as an etching and is still produced today as the original (Fig. 10a, b).

Jasiński also showed his works in the exhibitions in the Glaspalast in the ensuing years. He painted pictures of figures with religious scenery, such as “Feast day mass” or “Palm Sunday”, created rustic scenes, which played out indoors or in the surrounds of the village, landscapes, portraits, pictures of children, and some large-format symbolic compositions and allegories. When he was photographed by Teufel, the painter was working on a presumably allegorical composition with two sisters, graces or nymphs in a dramatic, large-format landscape – he was well dressed in a professional but unobtrusive pose. His atelier was in the Munich Art Academy.[116] That is why there are no homely decorations, carpets or wall panellings of any kind. Throughout his time in Munich, the artist was not listed under any other address. Another version of the small painting showing the child reading in the bottom left corner of the photograph possibly went to a collector in America because a colour art print was sold from there right into the 21st century showing the correct name of the artist and going by the title of “My First Picture Book”.[117] Jasiński returned to Warsaw in 1894.

When Teufel photographed Kazimierz Pułaski (Kasimir von Pulaski, 1861-1947)[118], he photographed a painter who had hardly come to anybody’s attention at this point, but who presumably had prominent proponents. Pułaski grew up in the family of his cousin Wojciech Kossak (1856-1942)[119] in Krakow, who himself had studied in Munich from 1873 to 1876 and had become an acknowledged painter in Krakow. Pułaski initially studied architecture at the Polytechnic in Riga and then served in the army. In 1889/90, he came to Munich to study painting. However, he did not enrol at the art academy presumably learning under Brandt instead, who he visited often in later years. Based on the style of Kossak and Brandt, he painted war and military scenes, equestrian and hunting pictures, but also landscapes and portraits. In the photograph, which was probably taken in 1893 (Fig. 13), he presents an as yet unframed painting that he has just finished with an arrangement comprising a saddle, a lateral sword, bags, belts, cartographic material and, as the highlight, a bird of prey with outspread wings, which he had previously constructed from actual equipment in front of a piece of material.

The painting looks like a sketch used for practice but the drawings lined up on the mantelpiece and the smaller to medium-sized paintings evidence the fact that the artist was already an accomplished painter. As he is not listed in any Munich address book, it is possible that Brandt or another member of the Polish colony recommended him to the photographer. The atelier seems to have been improvised and it is to be assumed that the artist had his sleeping area behind the curtain hung on a bamboo pole. However, it is still picturesque enough for the photograph to be of interest. Based on Brandt’s model, the artist had gathered together saddles and bridles, uniform caps, pistols and sabres, antlers and a target, which he had gone to some trouble to arrange in the small room. The family photos lined up on a shelf and on the table underneath also indicate that the artist didn’t just work here, he also lived here. In 1893, he exhibited at the Annual Exhibition in the Glaspalast just one, showing portraits of people on horseback, these being “Lieutenant Colonel Baron v. R.” and a “Captain von F.”. In the catalogue, his address is listed as Heßstraße 37 in Maxvorstadt.[120] In 1895, he went to Berlin to work with Kossak on creating historical panoramas in his atelier, but returned to Munich time and again to visit Brandt.

With the exception of Pułaski, all the Polish artists that Teufel had selected from 1889 for his atelier photographs had already been living in Munich for years or even decades. Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski, Kozakiewicz, Streitt, Rosen, Czachórski and Ejsmond had already come to Munich in the sixties and seventies, Suchodolski, Buchbinder and Jasiński arrived between 1880 and 1885. Publicly they formed, to all intents and purposes, the core group of the Polish artists colony which was named time and again in contemporary publications with a changing membership and with the addition of additional painters. In his discourse about the Munich School of Painting published in 1887, Adolf Rosenberg explicitly mentioned the existence of the “Polish Colony” and named Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski, Czachórski and Kozakiewicz, but also the late Maksymilian Gierymski (1846-1874)[121], Jan Chełmiński (1851-1925)[122], who was already living in New York, and Fałat and Szerner, who were already working in Berlin, as its most important members.[123]

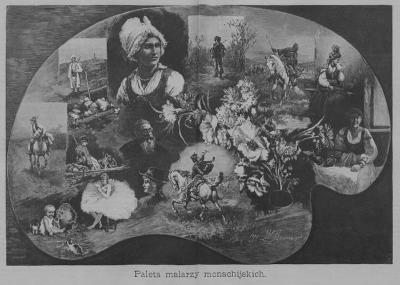

In his “History of Munich Art in the Nineteenth Century”, Friedrich Pecht acknowledged Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski, Kozakiewicz, Czachórski, Suchodolski, Buchbinder, and Gierymski, Kurella and Włodzimierz Łoś (Waldemar Los, 1849-1888), who lived in Munich[124], Chełmiński and Świeszewski, who had worked in Munich to the end of his life in 1895 and who had already worked on the “Album of Polish Artists” (see PDF) in 1876. In November 1887, the Munich magazine Kunst für alle depicted an artist’s palette, which went by the title “The Poles in Munich” and which Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski, Rosen, Buchbinder, Ejsmond, Szerner, Fałat and Bohdan Kleczyński (1851/52-1920), who had worked in Munich until 1888[125], had each painted with motifs that were typical to them.[126] In 1890, the Warsaw magazine Tygodnik Ilustrowany showed another painted palette entitled “Paleta malarzy monachijskich/Palette of Munich Artists” (Fig. 23) with motifs from Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski, Rosen, Streitt, Kozakiewicz, Czachórski, Buchbinder, Ejsmond as well as Szerner, Aleksander Gierymski and the Munich-based painters Wacław Szymanowski (1859-1930), Józef Wodziński (1859-1918) and Michał Gorstkin Wywiórski (1861-1926).[127]

Around 1891, paintings by Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski and Aleksander Gierymski could be seen in the Neue Pinakothek, which filled the members of the Polish artist colony with pride when they were hung in the permanent collection, particularly since Brandt signed his paintings with the suffix “z Warszawy” (in English from Warsaw) and with the Polish-speaking place name “Monachium” instead of “Munich”.[128] When Prince Regent Luitpold died in 1912, paintings by Brandt, Wierusz-Kowalski, Czachórski, Chełmiński, Stanisław Grocholski (1860-1932)[129] and Wywiórski were found in his art collection.[130] At the time that Teufel was creating the majority of his atelier photographs, that is to say 1889/90, many Polish artists had, of course, just left Munich or were already long gone. Take Apoloniusz Kędzierski (1861-1939)[131], for example, who returned to Warsaw in 1889 after four years of study, or Ludwik de Laveaux (1868-1894)[132], who moved to Paris in 1890. Others studied in the first few semesters at the Art Academy, such as Władysław Pochwalski (1860-1924)[133] or Józef Puacz (1863-1927)[134] or came very much later.

Judging from the Polish artists that Teufel selected for consideration, he must have got his list of names form the circle around Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski. However, if all the really established Polish artists in Munich had been considered, the list could have been a lot longer: Szerner, a painter of accomplished equestrian scenes, who had studied in Munich from 1865 and worked for a long time in Brandt’s atelier as an assistant, stayed in Munich until the end of his days in 1915. His atelier was located on the third floor above that of Brandt at Schwanthalerstraße 19, whilst he lived in Goethestraße 29[135] not far from Wierusz-Kowalski. Olga Boznańska, a highly talented and proficient figure and portrait painter, who had studied in Munich under private teachers since 1886 and who took part in the exhibitions in the Glaspalast from 1888, opened her own atelier in the following year, which she successfully ran until she left for Paris in 1898.[136] Aleksander Gierymski, who had studied in Munich from 1868-72, was back in the city from 1888 to 1890 and painted, among other things, his famous Munich cityscapes by night. In 1890, the Neue Pinakothek acquired its painting of “Wittelsbacher Platz”, that had previously been awarded a medal in the Annual Exhibition in the Glaspalast.[137] His atelier was at Amalienstraße 49 in Maxvorstadt, but he lived in Adalbertstraße 27.[138] In 1890, Otolia Kraszewska (1859-1945)[139], a painter of figures and interiors who had trained at the Art Academy in St. Petersburg, came to Munich, lived at Sophienstraße 5 in Maxvorstadt, took part in exhibitions in the Glaspalast from 1892 and remained in the Bavarian capital to the end of her days.

Also established in Munich at this time, was the landscape painter Roman Kochanowski (1856-1945)[140], who had come to Munich in 1881 after studying in Krakow and Vienna and worked as an artist in Munich until the end of his life. In all, the Munich Art Association acquired ten paintings from him in 1890 and in the following years and they were then raffled off amongst the members as an annual prize. Kochanowski resided at Landwehrstraße 29.[141] From 1880 and 1881 respectively, Szymanowski and Grocholski studied in Munich and between 1891 and 1893 opened a private painting school together in a house in Munich-Pasing, where numerous Polish artists studied. Kurella, who visited the Munich Art Academy from 1861 to 1867, was friends with Brandt, the Gierymski brothers, Józef Chełmoński (1849-1914)[142] and Czachórski, and was one of the most active members of the Polish artist colony. He painted genre themes from village and small-town life in Poland as well as religious scenes, lived at Schwanthalerstraße 36[143] and worked as an artist in Munich until 1897. Wywiórski studied at the academy from 1883 to 1887, but had also taken private lessons in the ateliers of Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski and followed the style of their motifs at the beginning. He travelled throughout Europe and in 1889 travelled with Wojciech Kossak to Egypt to prepare a panorama about the “Battle at the Pyramids”. In Munich, he lived at Theresienstraße 148.[144] In 1894, he went to Berlin to work in Kossak’s atelier, with Pułaski following him a year later.

The furnishing of the Polish artists’ ateliers with their collections and paintings on display, just as Teufel had photographed them around 1890, certainly lived up the expectations of the public, i.e. the high-ranking visitors, collectors, and gallery owners, who expected from the Poles nothing less than an unknown, “exotic” or ideally a picturesque Europe,[145] which even resembled the “orient” when the Turkish wars or the people, landscape and acts of war from the eastern borders of Poland were involved. The impression that the Polish art of painting was different persisted over decades, even if it mainly related to the core group of artists around Brandt and Wierusz-Kowalski. In January 1875, the Munich art critic and curator at the Alte Pinakothek, Adolf Beyersdorfer (1842-1901), wrote in the Viennese daily newspaper “Neue Freie Presse”: “Gierymski and his associates thus show the world in its poorest garb: a Polish dump, a patch of Puszta with scant grass and undergrowth and six miles of free views into the blue – sometimes some extravagance in the foreground, e.g. a bunch of thistles or a water pool – a moor tavern, with chalk white walls turned to the sunlight or an entire village, a dark group of houses packed together at night or at dawn […], a real suicide atmosphere – in short, everywhere the deliberate soberness and desolation of a wretched nature.”[146] Nearly three decades later in 1903, the painter, architect and writer Stanisław Witkiewicz (1851-1915), judged that the paintings of Brandt and his circle portray a fairytale world to foreigners, “whose form, movements, actions and behaviours, clothes and weapons astonish observers with their exceptional nature.” One would have searched elsewhere in vain for such helmets, sabres, robes, such a mass of unusual things, picturesque inns, slanted straw roofs, muddy ditches, and derelict mills. [147]

The collections in the ateliers of the Polish artists, especially those of Brandt (Fig. 1, 2), Kozakiewicz (Fig. 11), Rosen (Fig. 14, 15) and Pułaski (Fig. 13), did not just serve as models for their paintings, they also attempted to preserve the museum-like impression of being something different and picturesque for decades. They certainly represented a piece of home for each individual artist, but were, at the same time, an important part of their sales strategy.

Axel Feuß. January 2018

Literature:

Album malarzy polskich. Serya pierwsza. Monachium, Warsaw 1876

Bagińska, Agnieszka: “Atelje jako rzecz malarska”. Pracownia Józefa Brandta przy Schwanthalerstraße 19 w Monachium/“Atelier as a painting subject matter”. Józef Brandt’s atelier at 19 Schwanthalterstraße in Munich, in: Monika Bartoszek (Publisher): Józef Brandt (1841-1915). Między Monachium a Orońskiem/Between Munich and Orońsko, Orońsko Exhibition Catalogue 2015

Baumgartner, Anna: Überlegungen zur „Exotik“ in der Malerei um Józef Brandt, in: Egzotyczna Europa, Suwałki Exhibition Catalogue 2015 (see below), page 33-35

Beck, Julius: Munich artist ateliers. Plauderei, in: Vom Fels zum Meer. Spemann’s Illustrierte Zeitschrift für das Deutsche Haus, 1st vol. 1889/90 (October/March), Stuttgart 1890, columns 229-249 and 397-414

Egzotyczna Europa. Kraj urodzenia na płótnach polskich monachijczyków/Exotic Europe. Heimatvisionen auf den Gemälden der polnischen Künstler in Munich, Suwałki Exhibition Catalogue 2015

Jednodniówka – Eintagszeitung. New edition, published by Zbigniew Fałtynowicz / Eliza Ptaszyńska, Muzeum Okręgowe w Suwałkach, Suwałki 2008, at the same time exhibition catalogue “Signature - anders geschrieben. Anwesenheit polnischer Künstler im Lichte von Archivalien”, Polish Cultural Centre, Munich 2008

Jooss, Birgit: “Bauernsohn, der zum Fürsten gedieh”. Die Inszenierungsstrategien der Künstlerfürsten im Historismus, in: Plurale. Zeitschrift für Denkversionen, 5, 2005, page 196-228

Jooss, Birgit: Das Atelier als Spiegelbild des Künstlers, in: Künstlerfürsten. Liebermann, Lenbach, Stuck. Max-Liebermann-Haus Exhibition Catalogue, Berlin 2009, page 57-66

Jooss, Birgit: “Ein Tadel wurde nie ausgesprochen”. Prinzregent Luitpold als Freund der Künstler, in: Ulrike Leutheusser/Hermann Rumschöttel (Herausgeber): Prinzregent Luitpold von Bayern. Ein Wittelsbacher zwischen Tradition and Moderne, Munich 2012, page 151-176

Joos, Birgit: Munich – die Stadt der Malerfürsten, in: Malerfürsten, Munich 2018 (see unten), page 41-51

Langer, Brigitte: Das Münchner Künstleratelier des Historismus, Dachau 1992

Malerfürsten, Bundeskunsthalle Exhibition Catalogue Bonn, Munich 2018

Mongi-Vollmer, Eva: Das Atelier des Malers. Die Diskurse eines Raumes in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts (= Dissertation Freiburg im Breisgau, 2002), Berlin 2004

Mongi-Vollmer, Eva: Das Atelier als “anderer Raum”. Über die diskursive Identität and Komplexität des Ateliers im 19. Jahrhundert, in: Paolo Bianchi (Herausgeber): Das Atelier als Manifest, in: Kunstforum international, vol. 208, 2011, page 92-107

Pecht, Friedrich: Geschichte der Municher Kunst im neunzehnten Jahrhundert, Munich 1888

Ptaszyńska, Eliza: Dunkle Wälder, nackte Ebenen and Schnee, in: Jednodniówka – Eintagszeitung, Suwałki 2008 (see above), page X-XIV

Rosenberg, Adolf: Die Municher Malerschule in ihrer Entwicklung seit 1871, Leipzig 1887

Stępień, Halina / Maria Liczbińska: Artyści polscy w środowisku monachijskim w latach 1828-1914. Materiały źródłowe, Warschau 1994

Ste̜pień, Halina: Artyści polscy w środowisku monachijskim. W latach 1856-1914 (Studia z historii sztuki / Instytut Sztuki, Polska Akademia Nauk, 50), Warsaw 2003

Stepień, Halina: Die Welt der eigenen Empfindungen, in: Jednodniówka – Eintagszeitung, Suwałki 2008 (see oben), V-IX

Teufel, Carl: Ateliers Municher Künstler [100 photographs], vol. 1 (A-H), vol. 2 (K-P), vol. 3 (R-Z), Munich (1889)

Online resources:

Carl Teufel: Ateliers Münchener Künstler, 3 volumes, Munich (1889) http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0011/bsb00110288/images/, http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0011/bsb00110306/images/, http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0011/bsb00110307/images/

The cited address books of the City of Munich can be viewed in the Bavarian State Library using the search term “Adressbuch von München”, under the item “1845-1906; 1912-1918” and the button “online lesen”, https://opacplus.bsb-muenchen.de/metaopac/start.do

The cited exhibition catalogues of the Munich Glaspalast are available on the webpage “Kataloge der Kunstausstellungen im Münchner Glaspalast 1869-1931” of the Bavarian Regional Library online, https://www.bayerische-landesbibliothek-online.de/glaspalast

(All links were last retrieved in December 2018.)