Moments of what we call history and moments of what we call memory

Mediathek Sorted

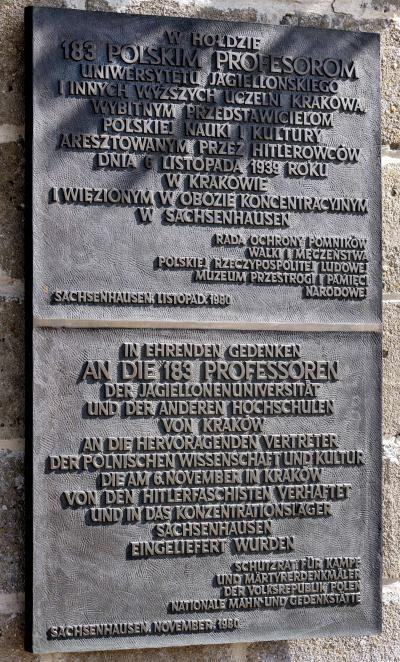

Back to Marian Stefanowski’s photographs. To the empty, frightening, clean, tidy “wide space” in which, sporadically, small groups of people can be seen who are not caught up in any crimes or suffering and who are not subjected to an extreme existential experience of the spirits of the past but, instead, belong in our time, whilst seeming lost between the gruesome artefacts, the fragments of history and the wide spaces opening up before them. They are searching for their own way and their own answer. The question is just how does it turn out?

The photographer’s cool and aloof eye fails to provide us with any reliable solutions this time either.

And so we come to the point at which the experience of the Sachsenhausen camp also becomes my own experience thanks to Marian Stefanowski’s camera, an experience that I have encountered as an open and repetitive question; a question about an idea, about perceptions and about the psychosocial mechanisms that justified both the collective and the individual violence in its countless forms and variations. A question of the ubiquitous presence of these ideas in all possible social systems, sometimes covert, discrete and banal, but also familiar and rationalised, and only seldom influenced by a tragedy which openly breaks out under certain circumstances and shocks the general public. In this sense, there are no more questions about Nazism as such, although the extent of the atrocities, of which it was the source and direct perpetrator, can be neither overestimated nor forgotten. National socialism with its system of stigmatisation, of isolation, of dehumanisation and of destruction discloses in an exemplary manner - after all, Sachsenhausen was the system's flagship designed and conceptualised as a model of a model - as a consequence of a mindset pushed to its extreme, which is ever present in human societies, and of the relevant categories and perceptions. Everything is a question of circumstances, possibilities and dimension. Perhaps we will not have to wait very long until we get barbed wire and watchtowers again? And looking from a global perspective: did they ever really disappear? That would really be too much of a moral luxury.

However, should there ever be some kind of private form of remembrance at this place, my somewhat private museum of innocence,- because who am I to decide for others? - if would be exactly this.

So let us consider our social certainties and structures sceptically, let us ask and scrutinise. Questions as such seldom end in murder. Unlike the unwaveringly reliable answers that leave no room for doubt.

Krzysztof Dudziak, June 2020

Editor: Magda Potorska