Moments of what we call history and moments of what we call memory

Mediathek Sorted

A reminder of the perpetrators understood thus goes beyond the explicit narrative of the camp experience, although it does not in any way diminish the uniqueness and the terror of this experience. It gives an indication of something else relating to the criterion. Of something that one can and should search for in oneself as well as in the structures of one's own world. At the same time, it appears that only the linking of the empathetic reminder of the victim with the cognitive reminder of the perpetrators, or with the social and mental structures that determine it, facilitate an effective, formative realisation which is so different to the tribal perspective, even if this perspective is just as effective and formative in its own way.

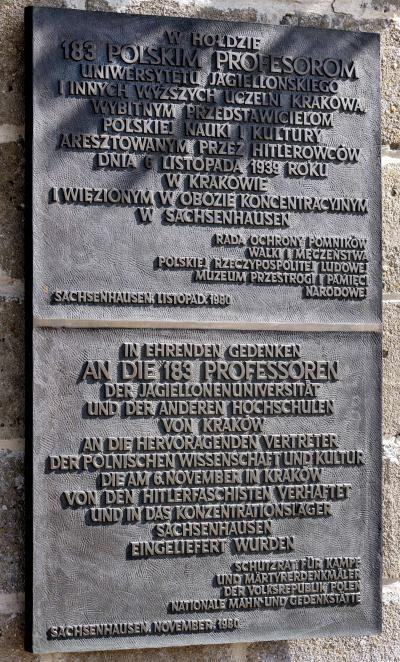

In all this, is it possible that memory petrifies as time goes by and, as the great-grandchildren of the witnesses from that time grow up, assumes a form found in museums that does not have any personal relevance anymore? A form which does not bother us any more than do the bloody excesses of Assyrian monarchs, the atrocities of Tamburlaine or the organisational structure of the prisons on the Latifundia of the Roman Republic? Sachsenhausen? Yes, that is the place that travel guides describe as an interesting place “near Berlin” that they recommend for a day trip. What is correct is that this place documents drastic and bloody stories, evokes strong emotions which trigger simple reflections about the darker sides of human nature, but overall it is too outlandish and too far removed from the everyday to be able recognise such thoughts as a meaningful narrative about oneself and about one’s own world. Perhaps the stereotypical conclusions drawn by the users and reviewers of the travel portals, by the hurried consumers of tourist attractions or by those who want to experience great emotions are proof of this? It is worth taking comfortable footwear and an umbrella in case it should rain and then have a look at the list of recommended restaurants nearby because human beings are known to get hungry after touring around for hours at a time...

All of this embodies the vision that one of my school friends pointed out in a moment of youthful rebellion when weighed down by all the camp literature on the reading lists: they are warning us by reminding us of these horrors. But would it not perhaps be better to forget them? And if mankind should ever get the idea again to do similar things in the future, would they potentially find them too innovative, too avant-garde? At the time, the question made sense but after so many years, particularly today in the context of the photographic narrative by Marian Stefanowski, I feel compelled to deny it. In the continued creation of new forms of enslavement, of degradation, of exploitation and of killing and in the systematic justification of such things, mankind is characterised by an inventiveness which is not restricted by tradition and, if it is ever impeded then, it is usually due to technological hurdles. For this reason, and not as a result of moral decay, the intensity of the horror reached its peak in modern times. Even if there is no evidence that earlier collective experiences have ever stopped a community from committing crimes, I am advocating quite decidedly for a vigilant, sensitive, empathetic and dedicated nurturing of the memory. You have to be able to back something. Ultimately, it is a moral decision for each of us.