Moments of what we call history and moments of what we call memory

Mediathek Sorted

Moments of what we call history and moments of what we call memory

There is a profusion of empty, tidy, well tended areas. Without people. Sure, an anonymous person or a group of visitors sometimes pops up, captured when they are inspecting part of the exhibition, which was expertly put together and which- as all the guide books will tell you - provides extensive information. But all of this constitutes a vague backdrop. They are guests from another world, strangers. There are no silhouettes or ghostly shadows of the main perpetrators of the terrible drama. This absence is perplexing and disturbing at the same time. The more I go from image to image, the more I am convinced that this absence is no coincidence. It must be the photographer’s intention in some way. At the very least, it represents a trail which entices the observer to follow it.

I have never been in Sachsenhausen and have never visited a concentration camp. I have not felt any need to visit there, but not because the existence of the camps and their history is inconsequential. Quite the opposite. Since my school days, and I belong to the generation that was fed books and knowledge about the Second World War in abundance, the experiences in the camps have raised a number of questions for me: questions about the people, about their culture and history, about their self-image, about the moral and social order which the people creates, and which they create in an uncompromising, concentrated and even brutal way. These were not historical questions; they were purely anthropological questions. The camp experiences constitute an unprecedented borderline experience, not the first and not the only one, but extreme and close enough in terms of time that they are not just repressed as an historical fossil that troubles one's peace of mind. I was aware of all that when I read books and when I watched films. So what would the visits have been able to add, apart from an emotional downpour on the paths of the crime, on the places of torture? This is all the more true because the encounters with the past at such places are not direct: the camp that we visit is not a real camp, our situation does not reflect in any way the situation faced by the victims. It does not reflect the executioners’ situation either. You can save yourself the trouble.

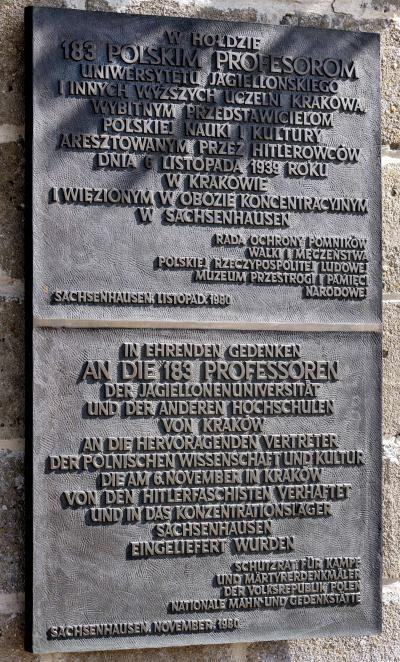

Was that a typical attempt on my part to rationalise my fear? Most definitely, yes. I have looked at Marian Stefanowski’s photographs of the Sachsenhausen camp with increasing interest. Possibly for the very reason that in this case we are dealing with a realisation that is conveyed gradually: we perceive the traces of the empirically inaccessible past through the vision, the perspective and the selection of someone else. As well as the question of the subject matter, the question of the medium is also raised, which in this case takes on the role of an emotional buffer. I found Stefanowski to be a discrete and transparent medium. Hidden behind his subject, he has created a cycle of completely neutral, detached and cool photos in which he dispenses with the need for artificial expressions and commentaries which could entice the observer into doing something. His photographic documentation subjugates itself completely to the place in question, is proficient and systematic. It shows memorials, general outlines, individual exhibits, commemorative plaques, sporadic groups of visitors and...a great deal of open space. Ordered, clean, well maintained space, which despite everything and despite the quiet is still enclosed by barbed wire and watchtowers as it was in the past. A cleared stage awaiting the next act of a drama? For me personally, this is not a metaphor, it is a deliberate moment of remembrance in which we find ourselves in the here and now. The last witnesses are dying out, the generational emotional and cognitive remoteness is growing. Ultimately, the memory of their experience is giving way before our very eyes to just our constructed memory. It is up to us to decide with whom, with what and in what way we fill this place that is devoid of people. It is up to us, the mysterious visitors who, depending on how great our own curiosity and how strong our moral principles, lend this memory a definitive form when we are confronted with this flood of dramatic information whilst being torn out of our daily routine. In confronting the problem, Marian Stefanowski leaves the final decision to the observer.

Why do people come here? What are they looking for? What do they take away with them? Perhaps a lasting impression? Theoretical knowledge? Deep-rooted experiences? Perhaps a feeling of guilt? A feeling of injustice? But what guilt or what injustice are we referring to here if they were not involved in the past horrors of this place? Do they then take anything lasting with them at all? We just do not know... And still they come here. The visitor statistics are impressive, as are the ratings on the travel portals. On Google Maps the average rating is 4.6 out of 5 stars, on Trip Advisor 4.8 out of 5, with the number of reviews stretching into the thousands. Added to this are hundreds of comments, but they do not provide any answers either. They always show the same phrases repeated like a mantra: a moving, deeply moving, painful experience... So it is a hard emotional experience.

These difficult feelings are probably the result of being confronted with the objects in the exhibition and with the explanations provided by the exhibition guides, whose competence and profound knowledge are underlined by the visitors, who then seamlessly move on to the practical information about suitable clothing and footwear, umbrellas and provisions. Their conclusion is generally one of sympathy for the place which is well worth a visit, or more precisely, which you simply have to have seen. But why? To experience some part of the difficult processing? No, it is alien to me to ignore experiences and emotions but … in the space which was captured objectively by the photographer, it is not quite so obvious. As I already mentioned, the observer needs a certain amount of prior knowledge and a lot of imagination. But sometimes he comes to the following banal conclusion: “This place shows how thin the layer of civilisation is that covers the primitive basic instincts of mankind”. This does sound a little better but the sceptic in me still has doubts: Is this supposed to be the conclusion that we are to draw about this place? What would the consequences of this then be? Defence of civilisation? It then begs the question what we actually want to defend? With what means? Against whom? Definitely against the world of basic instincts. And where is this world supposed to be? In us or in others? And if it is in others, what criterion of otherness is supposed to apply here? After all, even the Nazis defended civilisation, in the way that they understood it, and they defended it before those they considered to be a danger to them by using whatever means they considered necessary. Today there is consensus that in all these three points, they started with false assumptions, then got caught up in internal contradictions and threw themselves into crime. So just where do the boundaries of acceptable new interpretations lie? And how are we supposed to know that our new insights would be less wrong and would not lead us into crime or to abuse at least? And last but not least: Does the memory of the camp experiences that we create have any influence on the metonymy of a totalitarian system with all its consequences?

For me, the memory I write about is a dynamic complex made up of perceptions of the past whose role it is to organise current and past experience into something living and significant. I also write about the constructed memory because the perceptions of the past, which are based on sources and reports that are filtered and interpreted based on knowledge acquired at an earlier date, and the human’s value system that deals with these are not authentic and, what’s more, are unable to be authentic. Sachsenhausen extermination camp as a typical source of historical understanding can, without doubt, provoke various interpretations and defer to alternative forms of remembrance which allow various conclusions, positions and sensibilities. With a lack of reliable data, at this juncture I can only outline the possible motives schematically.

Primarily we have the tribal memory which is organised around collective reified categories which are, in turn, broken down into simple oppositions and logics of symbolic identities.

We and you. You us – we you. A matrix of mutual relationships and simple abstractions, which is seemingly embedded in the history from which it draws its legitimacy, whilst it actually encounters it in the form of a timeless myth that drives the mechanism of further quotations, repetitions and reconstructions. A useful tool, especially for developing the identity and the solidarity of one’s own group, admittedly at the expense of the overall perspective. We you – You us. A permanently open account - in the third, fourth and every future generation. You the evil ones – We the good ones. This form of memory has a long tradition, has existed forever really, even when the memory related to the experience of the horrors of totalitarianism in the 20th century. The more we remove ourselves from the events, the more this memory takes the upper hand in the official narrative that we are happy to feed. There is a certain inevitably therein. The generation of direct witnesses was very strongly influenced by the sensitisation for war experiences as a tragic and traumatic destruction of humanity, by its self-awareness and by the myths and illusions about progress, humanity and moral development. The horrors of war were a defeat and an obligation for each of these people. The perspectives that went beyond the boundaries of the tribal identities could no longer be so easily denied. Today, where almost all of the witnesses have died and the memory is less the product of one's own experiences and more an intellectual construct, the climate has changed. Military themes dominate the litany of officially requested designs. Fighting for the sake of fighting, torn from the military, political and social context completely, becomes the most noble manifestation of patriotism and it is once again sweet to die for the Fatherland. The war as such, or more accurately collective organised violence, is no longer an expression of the tragic regression of mankind, but instead becomes an openly discussed legitimate policy instrument and turns into the pursuit of common interests which are, of course, morally justified. But then are there any others at all? And isn’t this shift of emphasis clearly and symbolically demonstrated when the current Director of the Danzig Museum of the Second World War (Muzeum II Wojny Światowej), in a debate about a new exhibition formula, asks that the “positive aspects of war” be included in the didactic programme? Signum temporis.

Of course, this narrative does not contain the positive aspects of the concentration camps or the camp experiences, but in the face of the apparent enemy the latter are often and willingly exploited in the sense of ad-hoc policy and to establish discipline and social identity; the narrative is channelled and adjusted to the tribal schemes. And now I read reports in pro-government media about the visit of our country’s incumbent President to Sachsenhausen where he laid flowers on the commemorative plaque for Polish academics imprisoned here in the context of the so-called “Sonderaktion Krakau”. If the summaries are to be believed, the narrative of the address held to commemorate this occasion did not go beyond the national categories mentioned.

The Germans as persecutors – We as the victims. There are no other categories to describe it. That is not to say that this picture does not reflect reality. But for me it is much more that when the Sachsenhausen experience is only reduced to this, it just becomes a faulty memory, whilst the national generalisations, which do not explain anything further or specify anything, create a cognitively dubious image of reality. This is particularly noticeable in the context of the place at which such addresses are delivered: at the end of the day, the first prisoners of the national socialist regime that were subjected to the collective stigmatisation were German nationals. They were internal aliens who were a danger to the chimaera of national unity and to the national objectives and who suffered as an example for subsequent wars against external aliens. However, understanding this mechanism and demonstrating the inadequacy of homogeneous, national generalisations is secondary. Yes, you could even say that the narrative of the President in this respect is paradoxically and certainly unconsciously consistent with the official position of the NS regime which excluded “different” or “antisocial elements” from the “true” Germanness. That is the logic and that is the price of the myths of tribal identities and of the tribal memories organised around them.

Forming a counterpole to these opinions is the memory, which one could call universal and which consciously ignores all those collective categories that are so important in the description outlined above, or at least pushes it into the background. The purely personal situation, which is reduced here to a binary system of persecutor and victim characterised by the act of violence, is a model in which the specific opposition inevitably results, or at least can result, from the affiliation to the respective collective group. The categories themselves are accidental and arise from the specific historical circumstances. The exploration of these circumstances is to be prioritised over the great movements that led to tragedy, both with respect to the explanation of the events and to their interpretation, insofar as that is at all possible. At the same time, we are dealing with variables which do not allow the circumstances as such to be understood. Everyone can get into a depressing situation, irrespective of their role in society, the place or the time. This general moment has an important moral and cognitive dimension. In this variant of remembering, it is certainly easier to adopt the victim’s perspective. That is intuitively a moral or even an emotional reflex. Therefore, the predominant forms of this type of memory concentrate on the victims, on the revelation, the naming and the reconstruction of the memory of them, on the ritual respect for then and on the attempt to reconstruct each lifeline which was shaken by the persecution. The piety of those who accept this reconstruction is ethically valuable in itself because it is noble in attitude. If it is filled with empathy and compassion which, in turn, leads to a sensitisation for all the more or less drastic manifestations of repression, degradation and oppression, then all the better.

However, when we do not just react to the oppression that has occurred but also want to properly recognise its dangers and its different manifestations, it seems to me that it is then necessary to keep the reminder of the perpetrators alive and even the memory of the perpetrators themselves.

Who were they? What motivated them to commit their acts? What did they want to achieve? With what value system did they intend to rationalise their acts? Such a memory, which does not excuse anything but just does not want to accept moral judgements that are as plausible as they are simple, and instead endeavours to see in the perpetrators people like us who are subjected to the same psycho-social mechanisms, can provoke internal resistance. However, it does offer the opportunity to understand the events and thus to give us a kind of awareness, that is, in a sense a cognitive and moral filter which allows us to truly recognise the dangers in our own, familiar and all too obvious world. This conviction results from the fact that, in order for a system of repression to develop, which manifests itself in the opposition of victim and perpetrator, the attitude and the acts of the perpetrator is of uppermost, yes even of constitutive significance. Usually, the victim does not choose his role himself: The victim is chosen. Therefore, the fact that the framework of the situation is determined by another, dramatically restricts the victim’s freedom of action. I am not even thinking here of the camp sadists who simply enjoyed the violence they asserted. They are the last link in a long chain. I am much more interested in the chronologically and above all logically earlier phase: What systematic ideas relating to the organisation of a society, what views of humanity, what conceptual frameworks were able to cause this issue? What justifications, what rationalisations, what defence mechanisms? Don’t some people still find concepts to protect society from dangers to its cultural, ethnic and religious cohesion or to its identity constructs ostensibly rational?! Doesn’t the same apply to demands to intervene in a corrective manner when antisocial elements breach general norms and standards? Or resocialise the edges of society however they are defined? And what about repressive measures as an educational method at every level of society? And what is the situation with hierarchies and with discipline as undisputed values and links for human groups? Can the instrumentalisation of third parties be discounted as a human resource for enforcing values which favour a group? Or the subordination of the right of the individual to a self-determined life, starting with the defining of permitted life choices right up to the literal right to survive that should be dependent upon the fulfilment of arbitrarily defined criteria? All these clichéd concepts, these banal manifestations of everyday dominance and violence can be defended to a certain extent. Or at any rate they find people to defend them. They do not have to end in totalitarian horror, but they can do. And what is more, they are the humus upon which the horror is developed. So where is the line?

A reminder of the perpetrators understood thus goes beyond the explicit narrative of the camp experience, although it does not in any way diminish the uniqueness and the terror of this experience. It gives an indication of something else relating to the criterion. Of something that one can and should search for in oneself as well as in the structures of one's own world. At the same time, it appears that only the linking of the empathetic reminder of the victim with the cognitive reminder of the perpetrators, or with the social and mental structures that determine it, facilitate an effective, formative realisation which is so different to the tribal perspective, even if this perspective is just as effective and formative in its own way.

In all this, is it possible that memory petrifies as time goes by and, as the great-grandchildren of the witnesses from that time grow up, assumes a form found in museums that does not have any personal relevance anymore? A form which does not bother us any more than do the bloody excesses of Assyrian monarchs, the atrocities of Tamburlaine or the organisational structure of the prisons on the Latifundia of the Roman Republic? Sachsenhausen? Yes, that is the place that travel guides describe as an interesting place “near Berlin” that they recommend for a day trip. What is correct is that this place documents drastic and bloody stories, evokes strong emotions which trigger simple reflections about the darker sides of human nature, but overall it is too outlandish and too far removed from the everyday to be able recognise such thoughts as a meaningful narrative about oneself and about one’s own world. Perhaps the stereotypical conclusions drawn by the users and reviewers of the travel portals, by the hurried consumers of tourist attractions or by those who want to experience great emotions are proof of this? It is worth taking comfortable footwear and an umbrella in case it should rain and then have a look at the list of recommended restaurants nearby because human beings are known to get hungry after touring around for hours at a time...

All of this embodies the vision that one of my school friends pointed out in a moment of youthful rebellion when weighed down by all the camp literature on the reading lists: they are warning us by reminding us of these horrors. But would it not perhaps be better to forget them? And if mankind should ever get the idea again to do similar things in the future, would they potentially find them too innovative, too avant-garde? At the time, the question made sense but after so many years, particularly today in the context of the photographic narrative by Marian Stefanowski, I feel compelled to deny it. In the continued creation of new forms of enslavement, of degradation, of exploitation and of killing and in the systematic justification of such things, mankind is characterised by an inventiveness which is not restricted by tradition and, if it is ever impeded then, it is usually due to technological hurdles. For this reason, and not as a result of moral decay, the intensity of the horror reached its peak in modern times. Even if there is no evidence that earlier collective experiences have ever stopped a community from committing crimes, I am advocating quite decidedly for a vigilant, sensitive, empathetic and dedicated nurturing of the memory. You have to be able to back something. Ultimately, it is a moral decision for each of us.

Back to Marian Stefanowski’s photographs. To the empty, frightening, clean, tidy “wide space” in which, sporadically, small groups of people can be seen who are not caught up in any crimes or suffering and who are not subjected to an extreme existential experience of the spirits of the past but, instead, belong in our time, whilst seeming lost between the gruesome artefacts, the fragments of history and the wide spaces opening up before them. They are searching for their own way and their own answer. The question is just how does it turn out?

The photographer’s cool and aloof eye fails to provide us with any reliable solutions this time either.

And so we come to the point at which the experience of the Sachsenhausen camp also becomes my own experience thanks to Marian Stefanowski’s camera, an experience that I have encountered as an open and repetitive question; a question about an idea, about perceptions and about the psychosocial mechanisms that justified both the collective and the individual violence in its countless forms and variations. A question of the ubiquitous presence of these ideas in all possible social systems, sometimes covert, discrete and banal, but also familiar and rationalised, and only seldom influenced by a tragedy which openly breaks out under certain circumstances and shocks the general public. In this sense, there are no more questions about Nazism as such, although the extent of the atrocities, of which it was the source and direct perpetrator, can be neither overestimated nor forgotten. National socialism with its system of stigmatisation, of isolation, of dehumanisation and of destruction discloses in an exemplary manner - after all, Sachsenhausen was the system's flagship designed and conceptualised as a model of a model - as a consequence of a mindset pushed to its extreme, which is ever present in human societies, and of the relevant categories and perceptions. Everything is a question of circumstances, possibilities and dimension. Perhaps we will not have to wait very long until we get barbed wire and watchtowers again? And looking from a global perspective: did they ever really disappear? That would really be too much of a moral luxury.

However, should there ever be some kind of private form of remembrance at this place, my somewhat private museum of innocence,- because who am I to decide for others? - if would be exactly this.

So let us consider our social certainties and structures sceptically, let us ask and scrutinise. Questions as such seldom end in murder. Unlike the unwaveringly reliable answers that leave no room for doubt.

Krzysztof Dudziak, June 2020

Editor: Magda Potorska