Moments of what we call history and moments of what we call memory

Mediathek Sorted

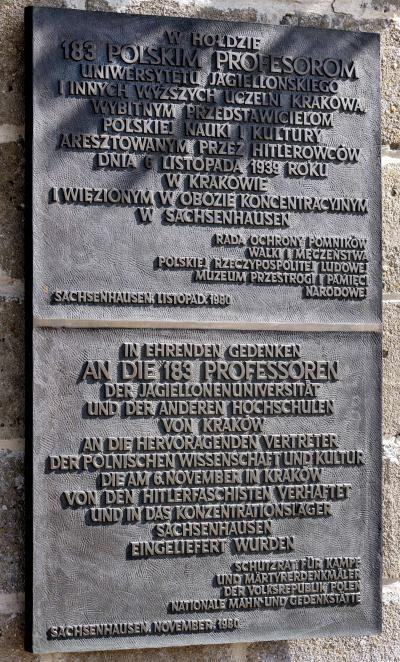

The Germans as persecutors – We as the victims. There are no other categories to describe it. That is not to say that this picture does not reflect reality. But for me it is much more that when the Sachsenhausen experience is only reduced to this, it just becomes a faulty memory, whilst the national generalisations, which do not explain anything further or specify anything, create a cognitively dubious image of reality. This is particularly noticeable in the context of the place at which such addresses are delivered: at the end of the day, the first prisoners of the national socialist regime that were subjected to the collective stigmatisation were German nationals. They were internal aliens who were a danger to the chimaera of national unity and to the national objectives and who suffered as an example for subsequent wars against external aliens. However, understanding this mechanism and demonstrating the inadequacy of homogeneous, national generalisations is secondary. Yes, you could even say that the narrative of the President in this respect is paradoxically and certainly unconsciously consistent with the official position of the NS regime which excluded “different” or “antisocial elements” from the “true” Germanness. That is the logic and that is the price of the myths of tribal identities and of the tribal memories organised around them.

Forming a counterpole to these opinions is the memory, which one could call universal and which consciously ignores all those collective categories that are so important in the description outlined above, or at least pushes it into the background. The purely personal situation, which is reduced here to a binary system of persecutor and victim characterised by the act of violence, is a model in which the specific opposition inevitably results, or at least can result, from the affiliation to the respective collective group. The categories themselves are accidental and arise from the specific historical circumstances. The exploration of these circumstances is to be prioritised over the great movements that led to tragedy, both with respect to the explanation of the events and to their interpretation, insofar as that is at all possible. At the same time, we are dealing with variables which do not allow the circumstances as such to be understood. Everyone can get into a depressing situation, irrespective of their role in society, the place or the time. This general moment has an important moral and cognitive dimension. In this variant of remembering, it is certainly easier to adopt the victim’s perspective. That is intuitively a moral or even an emotional reflex. Therefore, the predominant forms of this type of memory concentrate on the victims, on the revelation, the naming and the reconstruction of the memory of them, on the ritual respect for then and on the attempt to reconstruct each lifeline which was shaken by the persecution. The piety of those who accept this reconstruction is ethically valuable in itself because it is noble in attitude. If it is filled with empathy and compassion which, in turn, leads to a sensitisation for all the more or less drastic manifestations of repression, degradation and oppression, then all the better.

However, when we do not just react to the oppression that has occurred but also want to properly recognise its dangers and its different manifestations, it seems to me that it is then necessary to keep the reminder of the perpetrators alive and even the memory of the perpetrators themselves.