Karol Broniatowski. Presence and Absence in Sculpture

Mediathek Sorted

Karol Broniatowski's memorial to the deported Jews of Berlin

His approach to the design was simultaneously conceptual and dialectic. The memorial to the deported Jews is not only made manifest by looking at a heroic statuesque image, but also by walking along its path. The eternally absent bodies are materialised in the wall through their negative shapes, and call up associations with the imprints of the bodies of citizens who died in Pompeii and the scorched shadows of the victims who were vaporised in Hiroshima. By using concrete Broniatowski said that he wanted to remind people of the material that was most used in the Nazi period. It was not only used to build the “Reichsautobahn” (according to a dictum of the time: “Hitler’s will turned into concrete”), but also in the construction of thousands of air raid bunkers. This work by Broniatowski is also close to concept art, when we think of Sol LeWitt’s Hamburg memorial “Black Form - Dedicated to the Missing Jews” (1987/89), a black block reminding us of the destruction of the Jewish community in the Hamburg suburb of Altona.

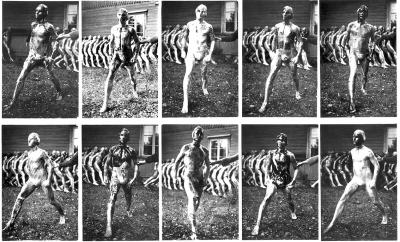

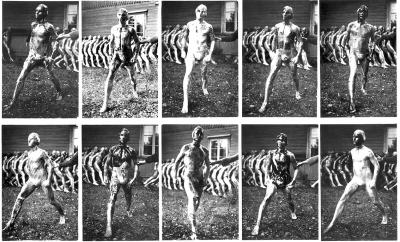

Starting in the mid-1980s Broniatowski’s independent sculptures continued to concern themselves with the human shape. Here, just as in his “Newspaper Figures”, he differentiated between striding male figures (ill. 18), typically shown in Greek Kouros sculptures, and standing female nudes, some of whom have their arms folded over their heads (ill. 19, 20), torsos (ill. 21) and interpretations of figures from Greek mythology like Gaia, Venus and Iris (ill. 22), all of which are bronze statues ranging in size from miniature to larger-than-life. There is also a conceptual link with “Big Man”. “Gruppe 93” (1986) consists of “small striding figures” (ill. 23), each of which, like “Big Man” and its later “presentations” of 93 individual parts, is simultaneously individual and uniform. They are all striding forward with their left leg in front, but each of them is differently designed and could stand alone or be placed together in formations.

His subsequent mid-size “Nudes” (ill. 19-21), just like the larger-than-life male “Striding Figures” (ill. 18) and the miniatures he made in the 1990s (ill. 22) take the previously observed principle to an extreme: a model kneaded and shaped by hand from lumps of clay is transposed into a rough, unsmoothed, disproportionate version to be cast in bronze. As in concept art and similar to the segments of “Big Man”, Broniatowski forces viewers, so to say, to use their experience and imaginative powers to reconstruct the natural form of the figure, its modifications or its antique predecessor from the mass produced by the artist. The over five-metre tall “Foot in Bendern”, made in 1996 for the LGT Bank in Liechtenstein (ill. 24), is one such “imaginative” model. There the seemingly amorphous mass of bronze only becomes an anatomic detail after the viewers have identified it – either from its title or from their own observation – as a foot, and reconstructed it is a gigantic figure in their imagination. Once more there is a close connection to “Big Man” because – when completed in the head – the final figure would reach a height of 30 metres.

Since 1989 Broniatowski has been making red and black gouaches on cardboard. These are really monotypes (one-time prints), where he projects the outlines and mass of his bronze works onto surfaces. (ill. 25). Here he uses variations on a process that we know from the reproduction of statues. He makes a plaster cast of the clay figures he has made by hand, thereby creating a negative hollow form. He then pours silicone into this form and withdraws it as a sort of skin to be used – after being painted – as a final printing block for the monotype. The concomitance and proximity between the negative forms manifested in the prints to the absent figures in his “Memorial for the Deported Jews in Berlin” have already been pointed out. Nonetheless the difference in the result seems to be more important: the print resulting from the projection of a sculptural figure onto a surface does not indicate its absence, but is rather the permanent trace of its existence. Finally, in an exhibition at the Polish Institute in Berlin 2012, these figurative silhouettes could not only be seen in groups, rows (ill. 26) and individually, but also as interactive pairs. Exhibition views bear witness to the close ties between Broniatowski’s bronze statues and his gouaches (ill. 27).