Karol Broniatowski. Presence and Absence in Sculpture

Mediathek Sorted

Karol Broniatowski's memorial to the deported Jews of Berlin

At the Venice Biennale, according to Skrodzki, “Broniatowski arranged a gigantic composition, whose conception had connections with Malczewski’s ‘Vicious Circle’. A crowd of figures (hung high above the heads of the visitors) twisted and turned in the space in front of the entrance to the Polish Pavilion ‘poured’ into the corridor and filled a part of the main room. This arrangement brought the artist great international success.” Equally in 1972 there were environments of “Newspaper Figures” in Ghent (Galerie Richard Foncke), 1973 in Antwerp (Galerie Zwarte Panter), Brussels (Palais des Beaux Arts) and in the Kunstverein in Mannheim (where the Mannheim Kunsthalle purchased an ensemble of 10 figures), and finally in 1975 at the Philadelphia Bourse. When compared to the general development of 20th-century art Broniatowski’s “Newspaper Figures” arrived early: we only have to think of the large groups of headless figures created by Magdalena Abakanowicz (“Clouds”, from 1983 onwards), or see them in relationship to the raw materialism of international sculpture in the 1970s and 1980s.

After a period of study in Belgium (1972/73) and time as a guest of the Copernicus Society in Ambler, Pennsylvania (1975), the artist received a grant in 1976 from the Deutsche Akademische Austauschdienste (DAAD) in Berlin. He remained true to sculpture, but his philosophy and working approach moved closer to concept art. With the aim of finding “a more universal way of portraying people who are forced into a flowing and unsettled form by information”, he developed an idealised walking figure called “Big Man”. In his imagination this figure became “gigantic”. It had a length of 18.8 metres, just enough to be able to turn into reality. It was “like the tallest fir in the forest in front of my workshop”, the only difference being that it was conceived as a recumbent relief. He divided it into a quadratic grid consisting of 93 parts, from which he created individual compartments – parts of the front of a foot and the fringe areas of legs, hips and the right shoulder (ill. 4) – made of Impala granite and packages of newspapers that had been screwed together (ill. 5).

The individual parts were placed in cities throughout the whole world, including Antwerp, Breslau, Łódź, Paris, Warsaw and Berlin. Classical sculpture came close to concept art; for the parts made of granite can only be identified as parts of human outlines with the help of information about the artist’s concept and the viewers’ own imaginative powers. References to urban sculpture, say by Ulrich Rückriem, or to American Land Art also spring to mind. Once again Broniatowski seems to function as a provider of ideas. For the American concept artist Jonathan Borowski (*1942), who in the mid-70s concentrated his work on rows of numbers (“Counting”) and drawings, only began designing over 20-metre tall schematic figures in public spaces in the 1980s (“Hammering Man”, Basel 1989; “Walking Man”, Munich 1995), which look like complete sculptural realisations of Broniatowski’s “Big Man” concept.

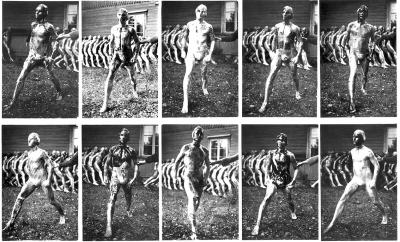

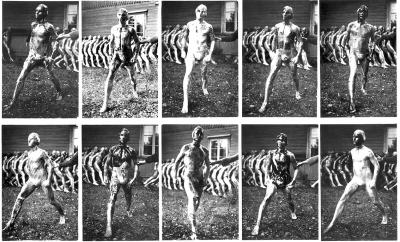

The “II Presentation of the Big Man” in 1977 in the Galeria 72 in Chełm, also had a concept character. Here Broniatowski represented the 93 individual parts by 93 bronze eggs mounted on a wooden board to make a work entitled “Object 93”, something which could be identified as Minimal Art without any foreknowledge of the connection (ill. 6). The “III Presentation of the Big Man” 1978 in the Dom Plastyka in Warsaw had the character of a performance. Here the artist encoded the 93 elements by hammering out the corresponding numbers in Morse code through a microphone (ill. 7). In 1979 the presentation of a head made of sand was also in the form of a performance in the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. At the start it was hidden in the hollow shape of a block of gypsum consisting of several parts, but later collapsed into a pile of sand when the gypsum segments were removed (ill. 8). “This is theatre of course, like so much of the fine arts for all their stasis and silence“, wrote George Tabori. Nonetheless the performance harked back to the basics of sculpture, the reproduction of sculptural figures in negative forms and thereby to the process whereby bronze statues are created. In 1981 these were joined by works with an experimental intention, with which Broniatowski bade farwell to bronze sculptures for good: individual parts of human figures that could be changed by the way they were assembled and dismantled (ill. 9), and a self-portrait from an abstract block, completed by the artist in 12 stages by adding more and more new layers (ill. 10 a, b).