Karol Broniatowski. Presence and Absence in Sculpture

Mediathek Sorted

Karol Broniatowski's memorial to the deported Jews of Berlin

Karol Broniatowski was born in Łódź in 1945 and studied at the Faculty of Sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych) in Warsaw between 1964 and 1970. He graduated as a master student under Jerzy Jarnuszkiewicz (1919-2005). During his time as a student he was thoroughly fascinated by the human figure in different stages of abstraction. Clay was his favourite material. For his graduate exhibition, however, he chose a new material, several layers of newspaper glued together with polyester resin, which he then re-shaped over a clay model to create life-size walking human figures (ill. 1a-c). “Using newspaper” said Broniatowski, “meant that I could create ‘uniform’ figures”, whose surface was, however, different from the collage-like arrangement of newspaper fragments. The reproductions made clear that the external shell of press photos and texts was “only an appearance, a forced form”, which contradicted the design of a sculpture and reflected the endlessly continuing changes to – and modelling of – people through information.

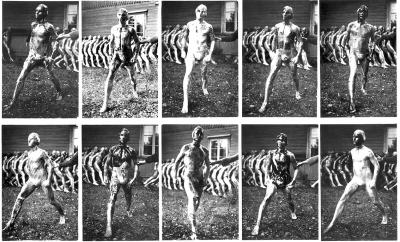

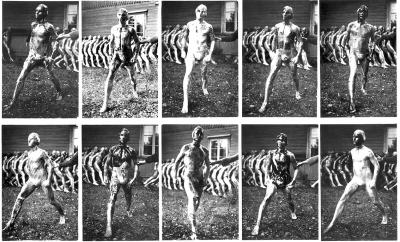

Lined up behind and opposite one another in the open air, and spliced into snapshots (ill. 2), the “Newspaper Figures” are reminiscent of the photographic sequences made by the British photo pioneer Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), who was the first to document motion sequences (The Human Figure in Motion, 1901). Even though Broniatowski had something utterly different in mind, the common element is still the filtering of essentials in the human figure – the way it moves and equally its social standing. Broniatowski differentiated between his male figures, who stride, and his female figures who stand with their arms folded over their head (ill. 28, 29). The relationship between the individual and the masses, personal roles and socialisation became one of the most important themes in sociology at the end of the 1960s: in Germany in particular in the lectures given by Jürgen Habermas (Stichworte zur Theorie der Sozialisation, 1968). With this in mind Karl Ruhrberg has described Broniatowski’s figures as “anonymous, they possess no individuality, they are simultaneously impersonal and supra-personal, they are equally ‘masses’ and ‘representatives’.”

In gallery spaces the artist brings them together in dramatically arranged environments, by hanging them from the ceiling as a moving group, having them walk or climb up walls in a particular direction, or even by placing them together in discussion groups. According to Mariusz Hermansdorfer, they are “portrayed as fleeing from something that threatens their existence and provokes a a general panic […] It is a community exposed to pressure, Terror and danger, a mass of people that you can indeed differentiate into individuals, but who are clearly unified by how they act and what they have experienced.” These environments caused a furore, which reminded Ruhrberg of the “proximity of theatrical tendencies to contemporary pictorial art, performances and happenings”, not only in exhibitions in Poland (Galeria Współczesna, Warsaw 1970; Biuro Wystaw Artystychnych, Lublin 1971, (ill. 3a); Galeria Arkady, Krakau 1971), but also at the Biennale in Venice in 1972 (ill. 3b). In Warsaw the environment was entitled “Threat”, in Kraków the headline was “Forced Landing”. “Threat”, according to Wojciech Skrodzki in the standard work “Contemporary Polish Sculpture” (1977), “was a link to the tragedy of the ‘September campaign’, whereas “Forced Landing” portrayed a more general situation grounded in the sensitivities of contemporary humanity. In both arrangements the gallery space was filled with bent over, walking human figures who exuded an atmosphere of panic, desperation and defencelessness.”

At the Venice Biennale, according to Skrodzki, “Broniatowski arranged a gigantic composition, whose conception had connections with Malczewski’s ‘Vicious Circle’. A crowd of figures (hung high above the heads of the visitors) twisted and turned in the space in front of the entrance to the Polish Pavilion ‘poured’ into the corridor and filled a part of the main room. This arrangement brought the artist great international success.” Equally in 1972 there were environments of “Newspaper Figures” in Ghent (Galerie Richard Foncke), 1973 in Antwerp (Galerie Zwarte Panter), Brussels (Palais des Beaux Arts) and in the Kunstverein in Mannheim (where the Mannheim Kunsthalle purchased an ensemble of 10 figures), and finally in 1975 at the Philadelphia Bourse. When compared to the general development of 20th-century art Broniatowski’s “Newspaper Figures” arrived early: we only have to think of the large groups of headless figures created by Magdalena Abakanowicz (“Clouds”, from 1983 onwards), or see them in relationship to the raw materialism of international sculpture in the 1970s and 1980s.

After a period of study in Belgium (1972/73) and time as a guest of the Copernicus Society in Ambler, Pennsylvania (1975), the artist received a grant in 1976 from the Deutsche Akademische Austauschdienste (DAAD) in Berlin. He remained true to sculpture, but his philosophy and working approach moved closer to concept art. With the aim of finding “a more universal way of portraying people who are forced into a flowing and unsettled form by information”, he developed an idealised walking figure called “Big Man”. In his imagination this figure became “gigantic”. It had a length of 18.8 metres, just enough to be able to turn into reality. It was “like the tallest fir in the forest in front of my workshop”, the only difference being that it was conceived as a recumbent relief. He divided it into a quadratic grid consisting of 93 parts, from which he created individual compartments – parts of the front of a foot and the fringe areas of legs, hips and the right shoulder (ill. 4) – made of Impala granite and packages of newspapers that had been screwed together (ill. 5).

The individual parts were placed in cities throughout the whole world, including Antwerp, Breslau, Łódź, Paris, Warsaw and Berlin. Classical sculpture came close to concept art; for the parts made of granite can only be identified as parts of human outlines with the help of information about the artist’s concept and the viewers’ own imaginative powers. References to urban sculpture, say by Ulrich Rückriem, or to American Land Art also spring to mind. Once again Broniatowski seems to function as a provider of ideas. For the American concept artist Jonathan Borowski (*1942), who in the mid-70s concentrated his work on rows of numbers (“Counting”) and drawings, only began designing over 20-metre tall schematic figures in public spaces in the 1980s (“Hammering Man”, Basel 1989; “Walking Man”, Munich 1995), which look like complete sculptural realisations of Broniatowski’s “Big Man” concept.

The “II Presentation of the Big Man” in 1977 in the Galeria 72 in Chełm, also had a concept character. Here Broniatowski represented the 93 individual parts by 93 bronze eggs mounted on a wooden board to make a work entitled “Object 93”, something which could be identified as Minimal Art without any foreknowledge of the connection (ill. 6). The “III Presentation of the Big Man” 1978 in the Dom Plastyka in Warsaw had the character of a performance. Here the artist encoded the 93 elements by hammering out the corresponding numbers in Morse code through a microphone (ill. 7). In 1979 the presentation of a head made of sand was also in the form of a performance in the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. At the start it was hidden in the hollow shape of a block of gypsum consisting of several parts, but later collapsed into a pile of sand when the gypsum segments were removed (ill. 8). “This is theatre of course, like so much of the fine arts for all their stasis and silence“, wrote George Tabori. Nonetheless the performance harked back to the basics of sculpture, the reproduction of sculptural figures in negative forms and thereby to the process whereby bronze statues are created. In 1981 these were joined by works with an experimental intention, with which Broniatowski bade farwell to bronze sculptures for good: individual parts of human figures that could be changed by the way they were assembled and dismantled (ill. 9), and a self-portrait from an abstract block, completed by the artist in 12 stages by adding more and more new layers (ill. 10 a, b).

Broniatowski has been living in Berlin since 1983. As early as 1981 he had taken part in design competitions for public spaces in Germany: in Berlin for the Europacenter on Breitscheidplatz; in 1984 a design for the planned memorial site on the site of the Prince Albrecht Palace, and another design for the square on the corner of Kurfürstendamm and Joachimsthaler Straße; and in 1983 in Frankfurt am Main for a sculpture on the new Römerberg (ill. 11-14). Here we can observe an extensive modelling of the terrain with different levels and steps (ill. 11, 12a), but also the division of large areas by means of columns and pillars (ill. 12b, 13). The stairway up to the memorial at the Prince Albrecht Palace was placed on a 40 x 40 metre area in the form of a pyramid turned on its head (ill. 12a). To a certain extent it was an ironic version of the stairway designed by the Nazi architect, Albert Speer (1905-1981) for the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg. But whereas the latter led up to the podium where Hitler gave his speeches, Broniatowski’s stairway was intended to lead visitors 12 metres downwards, where they would have been able to cross beneath the ruined site through a 1.5 metre high passage. For the Römerberg in Frankfurt the artist envisioned a monumental sphinx modelled on those in ancient Greece (ill. 14).

In 1984, also following a competition, he was commissioned to design a fountain on Franz Neumann square (between Markstrasse and Residenzstrasse) in the Berlin suburb of Reinickendorf. Corresponding to the shape of the square he came up with a triangular fountain with three levels, on each of which was placed a larger-than-life bronze female nude: one sitting, one kneeling and one lying down (ill. 15a-c). The figures were cast in the Hermann Noack Fine Art Foundry in Berlin. The foundry had already worked on sculptures by Ernst Barlach, Henry Moore and later Georg Baselitz, and Broniatowski continues to work with it today. Immediately after the figures were completed they were seen by Michael S. Cullen who noted that there was “nothing joyful, but something rather contemplative” in their faces and probably also in their postures. Their surface deliberately displays the un-smooth structures of the clay models, a result of modelling the figures from individual lumps of clay. This approach was even clearer in Broniatowski’s works shown at the Warsaw Academy and in his own “Self-Portrait” made in 1981 (ill. 10a, b). In 1989 he created a row of pillars to accentuate the shape of the Albert-Einstein-Gymnasium in the Berlin suburb of Neukölln (ill. 16).

In 1991 he was given the job of designing a memorial “to the more than 50,000 Jews in Berlin, most of whom were deported by the Nazis from the Grunewald goods station between October 1941 and February 1945 and subsequently murdered in extermination camps”. The bodies commissioning the work were the Berlin Senate and the district of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. The first deportation train carrying 1,251 Jews left platform 17 of Grunewald station on 18th October 1941. Till the end of the war there were a total of 185 transports (they also departed from the goods station in Moabit and Anhalter station). Each of these carried more than 1,000 people, initially to the ghettos in Litzmannstadt (Łódź), Minsk, Riga and Warsaw, and from the end of 1942 onwards to the Theresienstadt ghetto and the extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Around 35 trains with 17,000 Jews left Grunewald station for Auschwitz.

Broniatowski’s design for the “Memorial to the Deported Jews in Berlin” (ill. 17a-c) was a more than 20-metre long concrete wall next to the current suburban railway station “Berlin-Grunewald” at the entrance to the goods station there. It props up and models the slope directly behind it, where platform 17 can be found. The visual design elements in the wall are recesses and negative shapes of human silhouettes that may be interpreted as the train carrying away the deported persons, but which, when seen close-up, are also tactile and tangible symbols of the perpetual absence of the deported Jews. As Lech Karwowski described them, they are “hollow traces of human presence left in a massive material”, that visitors can turn into illuminated figures shining in the darkness by placing candles there. Broniatowski gave the concrete wall its rough sculptural surface by means of a masonry saw.

His approach to the design was simultaneously conceptual and dialectic. The memorial to the deported Jews is not only made manifest by looking at a heroic statuesque image, but also by walking along its path. The eternally absent bodies are materialised in the wall through their negative shapes, and call up associations with the imprints of the bodies of citizens who died in Pompeii and the scorched shadows of the victims who were vaporised in Hiroshima. By using concrete Broniatowski said that he wanted to remind people of the material that was most used in the Nazi period. It was not only used to build the “Reichsautobahn” (according to a dictum of the time: “Hitler’s will turned into concrete”), but also in the construction of thousands of air raid bunkers. This work by Broniatowski is also close to concept art, when we think of Sol LeWitt’s Hamburg memorial “Black Form - Dedicated to the Missing Jews” (1987/89), a black block reminding us of the destruction of the Jewish community in the Hamburg suburb of Altona.

Starting in the mid-1980s Broniatowski’s independent sculptures continued to concern themselves with the human shape. Here, just as in his “Newspaper Figures”, he differentiated between striding male figures (ill. 18), typically shown in Greek Kouros sculptures, and standing female nudes, some of whom have their arms folded over their heads (ill. 19, 20), torsos (ill. 21) and interpretations of figures from Greek mythology like Gaia, Venus and Iris (ill. 22), all of which are bronze statues ranging in size from miniature to larger-than-life. There is also a conceptual link with “Big Man”. “Gruppe 93” (1986) consists of “small striding figures” (ill. 23), each of which, like “Big Man” and its later “presentations” of 93 individual parts, is simultaneously individual and uniform. They are all striding forward with their left leg in front, but each of them is differently designed and could stand alone or be placed together in formations.

His subsequent mid-size “Nudes” (ill. 19-21), just like the larger-than-life male “Striding Figures” (ill. 18) and the miniatures he made in the 1990s (ill. 22) take the previously observed principle to an extreme: a model kneaded and shaped by hand from lumps of clay is transposed into a rough, unsmoothed, disproportionate version to be cast in bronze. As in concept art and similar to the segments of “Big Man”, Broniatowski forces viewers, so to say, to use their experience and imaginative powers to reconstruct the natural form of the figure, its modifications or its antique predecessor from the mass produced by the artist. The over five-metre tall “Foot in Bendern”, made in 1996 for the LGT Bank in Liechtenstein (ill. 24), is one such “imaginative” model. There the seemingly amorphous mass of bronze only becomes an anatomic detail after the viewers have identified it – either from its title or from their own observation – as a foot, and reconstructed it is a gigantic figure in their imagination. Once more there is a close connection to “Big Man” because – when completed in the head – the final figure would reach a height of 30 metres.

Since 1989 Broniatowski has been making red and black gouaches on cardboard. These are really monotypes (one-time prints), where he projects the outlines and mass of his bronze works onto surfaces. (ill. 25). Here he uses variations on a process that we know from the reproduction of statues. He makes a plaster cast of the clay figures he has made by hand, thereby creating a negative hollow form. He then pours silicone into this form and withdraws it as a sort of skin to be used – after being painted – as a final printing block for the monotype. The concomitance and proximity between the negative forms manifested in the prints to the absent figures in his “Memorial for the Deported Jews in Berlin” have already been pointed out. Nonetheless the difference in the result seems to be more important: the print resulting from the projection of a sculptural figure onto a surface does not indicate its absence, but is rather the permanent trace of its existence. Finally, in an exhibition at the Polish Institute in Berlin 2012, these figurative silhouettes could not only be seen in groups, rows (ill. 26) and individually, but also as interactive pairs. Exhibition views bear witness to the close ties between Broniatowski’s bronze statues and his gouaches (ill. 27).

If we survey his closely intertwined themes, Broniatowski’s work is remarkable, not only in the context of Polish and German sculpture but also in an international context. It reflects and interprets not only neighbouring artistic genres like Performance art, Concept art, Arte Povera, Minimal Art, photography, drawing, urban design, art in public spaces, and fundamental problems related to memorials and memory culture. But it also offers answers to basic problems of sculpture: how to design masses of people in a sculptural form; how to reproduce them in positive as well as negative forms, all the way to a complete lack of form; how to project them on surfaces; how to show the influence of antique art on the Modern; and how to make a work of art interact with the person observing it.

Axel Feuß, June 2016

Further reading:

Karol Broniatowski. Big Man, Exhibition catalogue published by the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Berlin 1976

Andrzej Osęka / Wojciech Skrodzki: Polnische Bildhauerkunst der Gegenwart. German edition, Warsaw 1977

Karol Broniatowski, Exhibition catalogue published by the Deplana-Kunsthalle, Berlin 1984

Karol Broniatowski. Prace z lat 1969-1999, Exhibition catalogue published by the Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Zachęta, Warsaw 1999 (Polish/German)

Tür an Tür. Polen - Deutschland. 1000 Jahre Kunst und Geschichte, edited by Małgorzata Omilanowska, Exhibition catalogue published by the Berliner Festspiele, Berlin, Cologne 2011, pp. 612, 663

Karol Broniatowski. Gouachen, Exhibition catalogue published by the Polish Institute, Berlin 2012