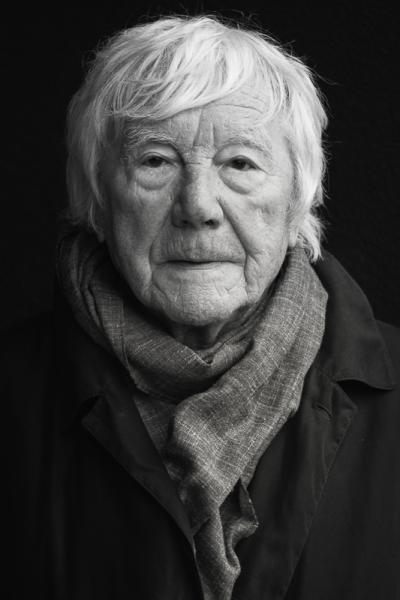

Janina Musiałczyk. W drodze, on the road

Mediathek Sorted

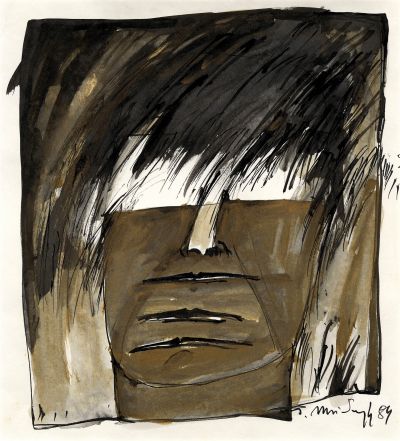

People stand, disoriented, between “boundaries” and “landscapes”. They look around and lose their face (1988, Fig. 22), emerge haltingly out of themselves before an earth-like background (Fig. 70) or stand rigidly between huge rocks, crammed alone into the narrow space (Fig. 71). As a couple separated by distance, both with their share of an over-powerful urban landscape, abandoned at night, they are no longer able to find their way back to each other (all 1988/89, Fig. 72). Musiałczyk later wrote: “I lay my head / into my heart / see all / I see, / I see and see / [...] see and weep / ... / I keep walking / narrow paths / unknown places” (Ich lege meinen kopf / in das herz hinein / sehe alles / ich sehe / ich sehe und sehe / […] sehe und weine / … / ich laufe weiter / schmale wege / fremde orte).[58] Her landscapes, beyond borders, created in and divided into “here and there”, are places of clear vision and bright awareness, in which the artist is nevertheless inescapably deeply rooted and buried in the earth.

There is a long tradition in Polish painting of expressing inner spiritual states through landscape elements. In the art of Young Poland (Młoda Polska), a heterogeneous artistic movement in the period around 1900, which at the European level is most closely comparable to Symbolism,[59] the most important Polish artists examined their own inner psychological states through “symbolic landscapes, in which a meaning was ascribed to every single element”[60]. For Jan Stanisławski, for example, water and clouds symbolised the past, while poplars swaying in the wind were the power of nature,[61] and earth was consistency, stability. In his painting “The Earth”[62], Ferdynand Ruszczyc portrayed “the ancient power and indomitability of nature, which puts mankind in its place”.[63] One critic saw “the soul of the artist” in the picture, which “gave expression to the soul of nature in a powerful, peaceful atmosphere”.[64] Wojciech Weiss, who was an enthusiastic admirer of Munch and his friend, the writer Stanisław Przybyszewski, used the dying nature of autumn to express transience and death, to name just a few examples.

Most landscapes of the Young Poland movement are devoid of people, unlike the landscapes of European Symbolism, such as those by Hodler, Böcklin, Kupka, Puvis de Chavannes, Segantini, Klinger and Munch, in which the human figure opens up further levels of interpretation. Six decades later, Fijałkowski used abstract images to create empty landscapes, which enable the viewer to project their own fantasies and states of mind. Against this wide background, Musiałczyk created an intermediate realm using elements of figurative abstraction, in which the landscape bestows on the human form a dramatic, but transient state of the soul.

[58] “I lay my head” (ich lege meinen kopf …), written in September 2002, in: w drodze_unterwegs 2015 (see note 32).

[59] See also Axel Feuß on this portal: Waren sie wirklich “Rebellen”? Zur Münchner Ausstellung “Stille Rebellen. Polnischer Symbolismus um 1900”, https://www.porta-polonica.de/de/atlas-der-erinnerungsorte/waren-sie-wirklich-rebellen-zur-muenchner-ausstellung-stille-rebellen.

[60] Urszula Kozakowska-Zaucha: Landschaften der Trauer und der Hoffnung. Naturdarstellungen in der Malerei des Jungen Polen, in: Stille Rebellen. Polnischer Symbolismus um 1900, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthalle München, Munich 2022, page 81.

[61] Jan Stanisławski: “Poplars on Water” (Topole nad wodą), 1900, oil on canvas, 145.5 x 80.5 cm, National Museum in Krakow (Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie).

[62] Ferdynand Ruszczyc: “The Earth” (Ziemia), 1898, oil on canvas 171x219 cm, National Museum in Warsaw (Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie).

[63] Kozakowska-Zaucha 2022 (see note 60), page 79.

[64] Ibid., page 79 f.