Janina Musiałczyk. W drodze, on the road

Mediathek Sorted

Shadows on the wall

“Christmas Eve. The wafer. On the big table, everything laid out as always, and a pineapple. I sit at the table for hours, drawing stones”. Three months previously, in October 1981, Janina Musiałczyk, her husband, and her daughter had moved once again into new, temporary accommodation, this time on the second floor of an apartment block in Hamburg-Steilshoop.

As the artist wrote in her book, “Drawings and Texts” (Rysunki i teksty. Zeichnungen und Texte), the buildings were more attractive than the ones on the Zgierska Stefana estate in Łódź, from where the family had departed in May 1981 on an odyssey first to Sweden, and from there to Germany. In this strange new world, it was a real comfort to share the apartment in Steilshoop with another family. Together, they were seven in all, “seven metal beds, seven pillows, seven blankets, seven bedsheets, seven chairs, one table and seven towels”. She spent many hours in the dining room with the pink, flowery wallpaper. Cockroaches scuttled across the kitchen floor at night. They were given a Christmas parcel from an unknown donor. On 13 December, the regime under General Jaruzelski had declared martial law in Poland. Since then, the family had listened day and night to programmes produced in Munich by the Polish section of Radio Free Europe.[1]

For Janina Musiałczyk, living spaces are a fundamental expression of human existence. Her parents’ apartment, rented rooms, temporary accommodation, and longer-term places of residence were dwellings and sanctuaries, while at the same time, they also acted as points of transition, as stations marking different periods in her life, or as places of refuge. In her mind, dwellings embody places of arrival and parting, of waiting for parents or a lover. They act as spaces for work and creativity, are an expression of social stagnation or steps towards affluence and happiness. Apartments become places of fear and change into spaces where celebrations are held. They radiate security and the hope for a better social and societal future. For the artist, places where she used to live become anchors of memory.

She begins the account of the journey through her life, which she wrote down in 2001 in Hamburg in her artist’s book “Drawings and Texts”, and which takes the reader from one place of abode to the next, in 1946, in a rear courtyard building in Pabianice, Poland. At that time, she was three years old, and her grandmother lay dying on the bed in the middle of the room under a white blanket.[2]

The following year, the family returned to Łódź, to ul. Bednarska: “Fourth floor, room with kitchen. Across the hall on the same floor, the laundry room with a huge vat for white boil washes. [...] I am alone at home ... I force myself into the gap between the stove and the wall and wait until my parents return home from work. On Saturday, after the big laundry wash, the bath. First Ela, then me, we climb up into the huge vat and wallow in the warm water”.[3]

Soon after, the family moved again. In 1948, they lived in ul. Dygasińskiego: “Ground floor, two long through-rooms and a small, square-cut kitchen. [...] From the bedroom window, you can see the house on ul. Bednarska, a red dressing gown hanging from the chimney. It’s a woman who took her own life. [...] In this apartment, it feels cramped. I look for a space to call my own”.[4]

In 1964, Janina, now an adult of 20 or 21, moved into the vacated room of an apartment occupied by a school friend. The following year, she switched to a small, bright room rented out by two elderly ladies. By then, she had been studying at the Art Academy in Łódź for eight semesters. At night, she designed silk shoulder cloths for a company that produced scarves, shoulder cloths, and ties. On weekends, her fiancé came to visit from Warsaw. The following year, they both sub-rented an eight metre-square room with a shared kitchen and bathroom not far from the park in the old town: “The cupboard, the sofa, the small table, two chairs and sheets of paper, rollers, canvases, paints, brushes”.[5]

In 1967, they moved a few streets further down, into their first proper apartment: “We paint everything dark blue: the small, square table, the armchairs, the cupboard in the hallway, even the doors and windows. [...] Here, in these 21 square metres, I complete my diploma, sell my first painting. We have parties here. Joanna brings big platters of hors d’oeuvres from the Grand Hotel”.[6] Soon afterwards, her daughter was born.

In 1978, when Janina Musiałczyk had been running the art group in the Palace of Youth (Pałac Młodzieży) for 11 years, they moved into a large apartment which they had bought themselves, in the newly constructed high-rise estate of Zgierska Stefana, in the Stare Bałuty district of Łódź on the northern edge of the city. “In my workroom”, she writes, “there is a huge loom. Above it, brightly coloured sheep’s wool, dyed in the bathtub. For hours, I weave tapestries with mallow flowers, trees, and landscapes. For sale. [...] Behind the window, huge high-rise apartment blocks. Windows lit up, rows of windows. A rhythmic composition. We sit on the floor on the small, round straw mat. Me and my closest students. We drink cocktails from high glasses. The time of long conversations”.[7]

Three years later, this period also came to an end. Under pressure from the political situation in Poland, the family left the country. On 27 May 1981, Musiałczyk writes, “we leave the apartment with three small suitcases and three umbrellas. Staszek, Zuzia and me”.[8] They first travelled to Malmö, where they spent two months living with acquaintances and with a Polish emigrant. From there, the journey continued to Hamburg, where they eventually arrived on 21 July 1981. A new odyssey began, which over the coming three months would take them to three hotels and a room in shared accommodation. Finally, at the beginning of October, they arrived in the high-rise estate in Hamburg-Steilshoop.

Two years later, in the spring of 1983, they remained on the same estate, but moved to a different building: “Fourth floor, three rooms, a balcony, carpeted floors left by the previous tenant, beige, dirty. The furniture in the bedroom also belonged to that tenant. A huge, white wall cabinet. [...] I hang drawings on the walls, an ever-increasing number of seeing stones”.[9]

At last, after an interim stop in Hamburg-Farmsen, the family found a permanent place to live in the autumn of 1987, in Hamburg-Volksdorf: “We paper the walls and paint them white. I hang up pictures. There are more and more of them. [...] In the spring, we eat breakfast on the balcony ... We invite guests, there is a mocha cake on the table [...] In my room, on the big wooden table, I draw the walks in black ink. On the wall, a photo drawing by Piotrek with the huge, black stone, Fijałkowski’s ‘Angel’ [...] I look out of the window, a rat scurries past along the fence. I call the local authority. ‘They are wandering rats, they move from one city to the next’”.[10]

Musiałczyk sets the indoor spaces of her life story on the right-hand side of her book opposite the external events, which take the form of a series of images created using graphics stamped with black ink. Hundreds of walking figures, hunched over, form at first orderly, then disintegrating, surging or marching masses, in more or less orderly rows or blurred groups, from which one or more figures charge out, fall over each other, stand alone in a circular centre, step out to the side of the multitude or move back into it. All the same, yet they are given a certain degree of personality through the differing application of colour, which initially has an intense depth, and which becomes paler as the stamping continues. The panels are part of the “Departure, Exodus” (Fortgang, Exodus) series created in 2000 (Fig. 45–48), which raises the artist’s personal experiences when leaving Poland to the general plane of forced flight. Having emerged from the mass of other people, the individual ultimately ends up in a battle against themselves (Fig. 49).

Musiałczyk depicted her emotional connection to houses and apartments at different temporal periods and in different picture series of her paintings and drawings. In 1993, closely linked to the themes surrounding flight and migration, she depicted people with handcarts walking along winding, spiral, upside-down paths in her series “Coming, Becoming, Going” (Kommen, werden, gehen) (Fig. 32–39, 42). The carts bear houses and entire towns, which the people carry with them as the ballast of memory. However, burdensome memories also include people who are tied firmly to backs, are fettered and pulled behind the walkers in long rows, dragged behind as a seated piece of baggage, or, ill and dying, are laid down in the cart together with the houses and towns. There are boarded up windows and doors on houses that are abandoned when the people leave, or which remain locked when they arrive.

In 1995/96, in the “Meetings on the Road” (Begegnungen unterwegs) series, she drew figures carrying entire towns on their backs and chest (Fig. 1). Others have formed pairs to set their house on wheels for their journey (Fig. 69) or draw it along with them as a side cart (Fig. 68) or balance it on their arm (Fig. 67), while at the same time juggling with wheels, which should ordinarily be helping them to move forward more quickly. All metaphors for an existence that fluctuates between moving and staying. Even in the third series, produced in 2012, the artist depicts a couple facing each other in an intimate pose, the male figure of which carries the house of his childhood and youth with him as a heavy burden (Fig. 51).

In the series “On the Road” (Unterwegs), we meet single figures and couples in large-format acrylic paintings who have set out on their journey crammed into houses, or in rooms set onto wheels, in prisons of their memory (Fig. 5, 6). In a later drawing in this same series (1998, Fig. 63), a giant-like female figure, who stands tall and self-assured, who walks through the landscape in heavy shoes, pulls a tiny house on wheels, which contains her homeland or precious memories, as a constant adjunct.

During that period, in a series of paintings and ink drawings called “It Teeters” (Es taumelt), the artist also produced images of houses and churches precariously stacked one on top of the other,[11] which remind the viewer of the pictorial world created by Marc Chagall. In paintings produced before the first world war, like his etchings in the “My Life” (Mein Leben) series (1922/23) produced after his emigration to Berlin, Chagall portrayed the everyday world of his home town of Vitebsk, the Jewish suburbs, and Russian villages. In these works, houses, streets, furnished interiors, and people float and knock against each other in an ordered chaos, and in so doing, become anchors of memory: “It seems to me that, far away from home, I was closer to that place, closer than many others who lived there...”[12] In his “Self-Portrait”[13], he too balances his parental home on his head: “Churches, fences, synagogues all around, simple and eternal like the buildings on the frescoes by Giotto [...] Here, on Pokrovskaya Street, I was born a second time”.[14]

The drawings produced by Musiałczyk for the Es taumelt series have a more dramatic impact, however. Haggard human figures, stiff with horror yet also in a state of high agitation, stand and lie on top of each other against the backdrop of a town. Their sturdy shoes and the wheels strapped on underneath indicate the start of emigration. The chimneys of the town smoke ominously (Fig. 40). Buildings disappear into the sky as though in an explosion; a ladder that has been put up leads to nothing but emptiness (Fig. 41). A face screaming in panic, forced into a black space, is set upon and tortured by rolling and flying wheels (Fig. 44).

“In art, the house is usually a metaphor for the space closest to the person, a symbol of refuge and protection”, writes the Hamburg-based Slavicist, Waldemar Klemm: “Here, however, carried on the person’s own back or in their baggage, as a trace of the past, something that is genuinely their own, it can also be a burden which makes movement more difficult, a space that is too narrow for the figures that are crammed into it, or something that is separate from the person, something they are unable to access. [...] After all, the most characteristic drawings are those in which the silhouettes are placed in rooms, similar to cages, finally and completely, not without having themselves contributed to it, abandoning themselves to the isolation in the house as prison”.[15]

However, Musiałczyk’s subjects don’t just herald “something ominous, an antagonism, a polarity that is impossible to overcome, an evil ending” (Klemm). In her series “Rented Rooms” (Mieträume), which she produced from the mid-1990s onwards as ink drawings and canvas paintings using different techniques, more conciliatory pastel tones dominate, which generate diffuse moods. In grid-like structures reminiscent of high-rise estates, figures, which look statically in different directions, come to rest.[16] At the same time, the people are arranged systematically in rows and are locked in box-like cells. The houses into which they boldly march in are new, with roofs, although it appears that escape from them is impossible (2002, Fig. 86). In dark moments, these “rented rooms” (1998, Fig. 43) seem like a lonely epicentre in a swirling maelstrom of life, which transforms the ecstatic joy of existence depicted by Henri Matisse[17] into the horror of never-ending isolation, as expressed by Edvard Munch in his paintings and graphic art.[18]

The series “For the Boy” (Für den Jungen) (1998–2000, Fig. 75–77) strikes a more conciliatory note. Musiałczyk created a house to live in and a protecting family for an isolated, lonely boy she discovered in a photo album. In the later series, “Ghosts and Houses” (Geister und Häuser) (2015, Fig. 64–66), the dread she herself felt as a child comes to the fore: Musiałczyk recalls that in 1948, “In the evening, before I go to sleep, I move the furniture, push it around like wooden blocks. It’s enough to push the sideboard out into the middle of the room, and there, behind it, I have my space”.[19] Her fear of houses and indoor spaces which are home to the ghosts of the past where the horrors of the present reside, are also reminiscent of the pictorial themes of Edvard Munch.[20]

Surrealist artists such as René Magritte, Paul Delvaux and Giorgio de Chirico turned abandoned buildings and interior spaces into background scenes of frightening, dream-like worlds that floated between life and death. In these spaces, day and night, the internal and external worlds,[21] past and present times,[22] merged with each other. Time stands still,[23] or terrifying events from childhood are invoked.[24] For the Hamburg art journalist Evelyn Preuß, Musiałczyk’s subjects are a “variant of Polish Surrealism”, suffused with a depth of feeling.[25] Wolfgang Till Busse, an art historian from Cologne, notices a “particularly poetic-surreal pitch”, which has its origins in an unconscious experience that has not been intercepted by external influences, when “the hand moves as of its own accord. In so doing, she uses the écriture automatique technique developed by the Surrealists during the 1920s”.[26]

The writer Franz Kafka developed an obsession with interior spaces and dwelling places. He found his parents’ apartment in Prague oppressive and frightening, and fled from there to Berlin in 1923 when he was severely ill in order to create a home of his own with his new life companion, Dora Diamant. Torn between a liberating idyll and financial hardship, he was forced to repeatedly search for new places to live there, too, until his illness prevented him from leaving his final abode. In his novels and novellas, he had already described a rented apartment on a suburban street in a remote town in North America as a prison ruled over by a prostitute.[27] There are attic rooms branching out in all directions, with lawyers’ offices and interrogation rooms; a boundary experience of human existence and the precursor to execution.[28] It is no coincidence that the metamorphosis of Gregor Samsa into an insect takes place in the room of Samsa’s parents’ apartment.[29] For Kafka, the rooms where he lived in Berlin also became places of terror. He and Dora were forced to leave their first home by the unfriendly behaviour of their unsympathetic landlady,[30] and the last place where they lived reminded him of an underground, labyrinthine badger’s burrow, in which sounds of digging brought on feelings of paranoia.[31]

Musiałczyk found paths to reconciliation. In one of her poems, which she wrote between 2001 and 2014 after travelling between Hamburg and Łódź, she recognised that the “shadow on the wall / around the door / has perhaps always / been here / has two legs / and two arms” (“schatten an der wand / um die tür / vielleicht immer / hier schon gewesen / hat zwei beine / und zwei arme”) – that the shadow disappeared at night and returned in the morning. The phantom, which was only visible in daylight, was nothing more than an image of herself: “shadows on the wall / head all / tousled” (“schatten an der wand / kopf ganz / zerzaust”).[32] In the paintings of the “Steps” (Stufen) series (2006–19, Fig. 79–83, 87), which she produced during the same period, she shows houses which, reduced to basic geometric shapes, exude security and joy of life with their bright, even glowing, colours. In an interview given in 2015 on the occasion of her exhibition “When searching for form, I find the anecdote” (Szukając formy znajduję anegdotę at the Galeria Nieformalna in Warsaw, she claimed that: “The four walls are important – safe and silent. No noise from the outside world penetrates them”.[33] Later, she said that for her, a real home means “Safety. Independence. [...] One has more space for oneself, and calm from the turbulence of the world”. However, the search for this place is “often a burden and a difficult path”.[34]

Images showing the deep emotional impact of events, memories and dreams

Musiałczyk developed her style of painting and drawing during a time in which new forms of figurative art and realism were becoming established in the US and Europe in numerous different manifestations. From the mid-1950s, or at the latest from the start of the 1960s, artists inspired primarily by Jean Dubuffet began to develop narrative, figural forms as a counter-reaction to abstract Expressionism and Informalism. Following an exhibition entitled New Images of Man 1959 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which showed works by Francis Bacon, Dubuffet, Alberto Giacometti, Leon Golub, Willem de Kooning, Nathan Oliveira, Germaine Richier and others,[35] the book “New Figuration” by the German painter and art writer Hans Platschek, which appeared that same year, and the term “Nouvelle figuration” coined in 1961 by the French writer and art critic Michel Ragon, described a figurative art which had existential human conditions, subjective fears, social isolation, cruelties, pessimism and catastrophes as its theme, and which was ultimately seen to be linked to the social and political turbulence that emerged during the Cold War.

Formal simplification and deformation of the figure, spasmodic, sweeping gestures, its confrontation with symbols, sombre colours or strong colour contrasts where characteristic of the style. The subjects of the works fluctuated between illusion and reality, and drew on Munch, Surrealism and, in a way closely related to Dubuffet, on children’s drawings and Outsider Art (art brut) for inspiration. This was followed by the development in the US of Pop Art and Photorealism, and in Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark with the colourful-expressive COBRA group, the Zebra group in West Germany, a New, or Critical Realism, and the Fantastic Realism with national elements in Austria and West Germany, which was a further development of Surrealism.

In Poland, a new form of 1920s Constructivism was created after the war, which developed into a strong national tradition that would last for decades. Socialist Realism, which was prescribed by the state in 1949, was opposed by the playwright and painter Tadeusz Kantor and by Władysław Strzemiński, who began by painting Constructivist works before turning to two-dimensional abstraction from 1928 onwards. Socialist Realism was officially abandoned in 1955. Travel to western Europe and the US enabled Polish artists to forge connections to the international avant-garde. As a result, New Figuration was able to find a foothold in Poland as “Nowa figuracja”. Kantor drew ordinary people from the street in situations fraught with tension.[36] Władysław Hasior created a “Group Portrait” from different materials, in the shape of a huge, black scarecrow.[37] Influenced by Bacon and Ronald B. Kitaj, Janusz Przybylski painted figures trapped in social roles and existential hardships.[38] From the time of his participation in the 1970 Polska figuracja, polski styl, polska egzotyka exhibition at the Galeria MDM in Warsaw, Antoni Fałat depicted mostly blackened individual and group portraits in dramatically distorted situations which filled the entire frame.[39]

Musiałczyk’s teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź, Stanisław Fijałkowski, had been a student of Strzemiński. He was also one of the most high-profile Polish painters of the 20th century, and for nearly 50 years was a lecturer, dean and professor at the Academy in Łódź as well as a visiting professor in Mons, Gießen and Marburg. During the 1960s, after an initial orientation towards Cubism, and influenced by the writings of Wassily Kandinsky, he developed a flat, abstract style, the clearly defined forms of which could also be perceived as abstracted objects in a poetical, transcendental reality.[40]

While Fijałkowski was also interested in Surrealism, in 1967, Musiałczyk wrote her diploma thesis under his guidance on a secondary aspect of art brut, the “The specific nature of naïve art”. While Dubuffet regarded art brut as being art by outsiders, since the mid-1960s, Naïve Art in the form of painting and wood carving by amateurs had become established at a high level in Poland, and later also gained traction as a recognised art movement in exhibitions throughout Europe. “Characteristic of naïve art”, Musiałczyk wrote, is “the presence of an idiosyncratic, self-generating, an original and intimate poetry, which is the emotional connection between the outer world and the world of intense inner emotional responses and experiences. In its images, there is an intensity of emotion that is relayed to the observer all the more in that it is not subject to an externally determined aesthetic and does without cultural references, while at the same time, its symbolism is elementary and readable. [...] Naïve art confounds through its lack of formulae and rules; it is an untamed art, the sole incentive of which is the deep need to produce in whatever way possible a picture of intense feelings, events, memories and dreams”.[41]

Musiałczyk also chose this “incentive” as the motto for her own art. Unlike her teacher, in her own independent work, she followed a figurative path, and in the broadest sense, her work could be ascribed to the New Figuration movement. She placed the human figure, as well as clearly definable objects such as houses, carts and landscape elements, in the centre of her images. With its focus on spiritual and existential human states, and its abstraction of objects, simplification of figures and their unusual gestures, her works most closely resemble the Nowa Figuracja that had become established in Poland during the 1960s, not only through the artists described above, but also as a result of the high-quality, unusually high-profile, Polish poster art of the time.

In the same year she completed her studies, she joined the Association of Polish Artists (Związek Polskich Artystów Plastyków, ZPAP) and participated in their exhibitions from that time on. From 1967, she also ran the group of studios dedicated to the fine arts in the Palace of Youth (Pałac Młodzieży) in Łódź, and in this capacity worked as an art teacher for children and adolescents. During her 14-year tenure as an art teacher, until her departure for Germany, she taught artists who would later become successful, including Marek Pabich, now Director of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Planning (Instytut Architektury i Urbanistyki) at Łódź Technical University (Politechnika Łódzka), the painter Dariusz Fiet, also a pupil of Fijałkowski, Iga Bielejec, who most recently worked as a book designer in Nierstein near Mainz, the Łódź-based graphic designer Małgorzata Misiowiec, the painter, object artist and photographer Tymoteusz Lekler, and restaurant owner Krzysztof Nast, who most recently worked at the Schloss Moyland Museum in Bedburg-Hau.[42]

In 1998, the painter Wojciech Leder, most recently the head of a painting studio and a professor at the Władysław Strzemiński Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Władysława Strzemińskiego w Łodzi), who was also a student of Fijałkowski, recalled the following at an exhibition by Musiałczyk in Hamburg: “I am lucky to have been a pupil of Janina Musiałczyk. She gave me guidance when I was at an age in which one is particularly susceptible to the world of illusions. After all, doesn’t our first contact with art take the form of carefully learning to imitate the way that nature appears to us?”[43]

According to the painter, performer, creator of animated films and professor at the Łódź Film School (Szkoła Filmowa w Łodzi), Mariusz Wilczyński, who also completed his diploma thesis under Fijałkowski: “The Palace of Youth (Pałac Młodzieży) was where I put all my energy. There, I met Darek Fiet, who later became an outstanding artist [...] or Marek Pabich, now a well-known professor of architecture. […] Janina Musiałczyk sparked a feeling in us that we were something special; we felt like Cézanne, Matisse or Renoir […]. At that time, we felt a huge compulsion, huge passion. That was the great achievement of Janina Musiałczyk, our painting and drawing teacher in the Pałac Młodzieży”.[44]

Apart from designing silk scarves and weaving tapestries, Musiałczyk also earned money by illustrating books and designing book covers. From 1967–1980, she worked for the Almqvist Wiksell Förlag publishers in Stockholm and the Wydawnictwo Łódzkie publishers in Łódź. Her work included individual abstract or representational covers and vignettes,[45] as well as the design for an entire children’s book, such as the poems and fables of Jan Huszcza, with colourful, expressively abstracted figures, landscapes and still lifes.[46] For a volume of poetry by Andrzej Biskupski,[47] she designed a black-and-white cover with imaginative forms that shifted between flowers and insects, or geometrically abstracted maritime scenes and landscapes for a book for adolescents by Adam Gruda, which was set bet between Warsaw and the Masuria region.[48]

She also exhibited her own independent artwork at an early stage. In 1969, in Bałuty, the northern administrative district of the five that made up Łódź at the time, she co-founded the artists’ group and cooperative gallery Grupa Plastyków Bałuckich, to which she belonged until 1973 and with which she showed oil paintings, large-scale works and installations in public spaces. In 1971, she was awarded an honour by the Polish Artists’ Association, or ZPAP.

The strongest link to her later work is the image series “The Earth”, which she produced from 1974–1980. The drawings, created with pencil, coloured pencils and black ink on paper, show women’s bodies that are closely connected to the soil and the landscape, which are attacked by birds with long beaks and fiercely spread wings (Fig. 25–26). Clearly, the female figures from symbolistic art, which have a close relationship to Mother Earth and nature, acted as an inspiration.[49] These figures are tortured by nightmares and catastrophes, as with Jacek Malczewski,[50] or are exposed without protection to animals, as with Paul Gauguin,[51] or have hands grabbing for them, as with Munch.[52] At the same time, Musiałczyk’s birds’ wings, which graphically spread out over the entire area of the picture, have the power of the Tachist style prevalent at the time, which was controlled by the subconscious. “My images contain a great deal about my feelings and thoughts”, the artist is quoted as saying a decade later. According to one review of an exhibition, it would appear that these moods and thoughts were predominantly of a resigned, depressive nature: “the woman, the earth, the tree, the wind, the grief, the pain, the loneliness, the sense of weakness”.[53]

In 1973, she received the special prize from the supervisory authority of the school district of Łódź “for extraordinary and innovative services in the field of education and social work”; in 1978, she received the prize awarded by the Polish Ministry of Education and Upbringing (Ministerstwo Oświaty i Wychowania) “for outstanding services in the field of didactic and educational work”. In 1979, two years before she left the country, she was presented with an honorary diploma by the Ministry for her “artistic quality and outstanding services in the field of art education for children and adolescents”.[54]

A piece of that other world

Musiałczyk’s decision to leave Poland brought themes surrounding departure, exodus, those left behind and passing landscapes to the fore of her artistic work, and continued to dominate it in the decades that followed. It proved advantageous that she had previously already worked in small formats on paper, and that now, in temporary, improvised accommodation, she could continue to produce series of drawings. She was only able to take a few of her own works with her on her journey. In Malmö, the “woven tapestry, a part of that other world”,[55] which had been purchased by the tenant of the apartment and which hung on the wall of one of the rooms.

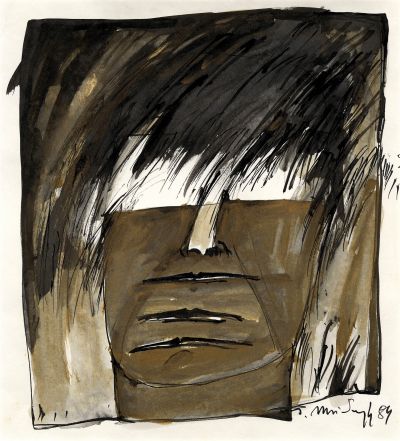

During the year of her arrival in Hamburg, she produced a series, entitled “81”, of abandoned landscapes, windswept by storms, which look at the observers as faces (Fig. 74), stood opposite them in the form of female bodies or in which chasms appear.[56] They are related to the “seeing stones”, which she began to draw in her first apartment in Hamburg-Steilshoop, and which covered more and more walls two years later. The drawings show stones or large boulders with static faces, which look straight ahead or diagonally, lonely creatures related to the stones in an open, barren landscape, fallen into ravines, as female bodies grown out of the ground or locked in box-like rooms; a reflection of a state of mind that is frozen in grief and turned to stone.

Until 1990, she produced numerous further series of drawings entitled “Divided Landscape, Created Landscape” (Geteilte Landschaft, gestaltete Landschaft), “Here and There” (Hier und dort) and “People, Borders, Landscapes” (Menschen, Grenzen, Landschaften), in which different techniques are used, and landscape elements and human figures are symbiotically linked. While the titles refer to the migrant conflict of belonging to two different countries and cultures, in the image motifs, different stages of deep-rootedness in the landscape are portrayed on the one hand in contrast to ejection, displacement, and alienation on the other.

The figures are usually female, floating as angels with broken wings over the “divided landscape”, (Fig. 4) or with legs flowing with blood between “here and there” (Fig. 15) (both 1983). They turn into petrified formations in the landscape, buried deep in the earth below plough ruts, windswept trees, village landscapes and cemeteries (1984, Fig. 9, 12–14). Or, like the protagonist in Kafka’s novella The Burrow (Der Bau), they have hidden themselves in underground holes against the dangers of life, usually as sleeping “creatures from within the earth” [57] and rolled themselves up like an embryo (1986, Fig. 11). Being a woman is one of the central themes in Musiałczyk’s pictorial world.

Earth-coloured, frozen faces with gagged mouths and bound eyes are reminiscent of the gag on free speech during the dictatorship (1984, Fig. 2, 3) and are written for all time into the landscape with its ravines and trees (1984, Fig. 24). They fall from the sky as screaming comets (1985, Fig. 55), stumble through the room as “seeing stones”, (Fig. 7), form heavy rock formations with their bodies and hide, bent over, in the rocky sediment (all 1986, Fig. 10, 16). Finally, hidden in deep ravines, they are themselves threatened by a falling rock (1987, Fig. 73).

People stand, disoriented, between “boundaries” and “landscapes”. They look around and lose their face (1988, Fig. 22), emerge haltingly out of themselves before an earth-like background (Fig. 70) or stand rigidly between huge rocks, crammed alone into the narrow space (Fig. 71). As a couple separated by distance, both with their share of an over-powerful urban landscape, abandoned at night, they are no longer able to find their way back to each other (all 1988/89, Fig. 72). Musiałczyk later wrote: “I lay my head / into my heart / see all / I see, / I see and see / [...] see and weep / ... / I keep walking / narrow paths / unknown places” (Ich lege meinen kopf / in das herz hinein / sehe alles / ich sehe / ich sehe und sehe / […] sehe und weine / … / ich laufe weiter / schmale wege / fremde orte).[58] Her landscapes, beyond borders, created in and divided into “here and there”, are places of clear vision and bright awareness, in which the artist is nevertheless inescapably deeply rooted and buried in the earth.

There is a long tradition in Polish painting of expressing inner spiritual states through landscape elements. In the art of Young Poland (Młoda Polska), a heterogeneous artistic movement in the period around 1900, which at the European level is most closely comparable to Symbolism,[59] the most important Polish artists examined their own inner psychological states through “symbolic landscapes, in which a meaning was ascribed to every single element”[60]. For Jan Stanisławski, for example, water and clouds symbolised the past, while poplars swaying in the wind were the power of nature,[61] and earth was consistency, stability. In his painting “The Earth”[62], Ferdynand Ruszczyc portrayed “the ancient power and indomitability of nature, which puts mankind in its place”.[63] One critic saw “the soul of the artist” in the picture, which “gave expression to the soul of nature in a powerful, peaceful atmosphere”.[64] Wojciech Weiss, who was an enthusiastic admirer of Munch and his friend, the writer Stanisław Przybyszewski, used the dying nature of autumn to express transience and death, to name just a few examples.

Most landscapes of the Young Poland movement are devoid of people, unlike the landscapes of European Symbolism, such as those by Hodler, Böcklin, Kupka, Puvis de Chavannes, Segantini, Klinger and Munch, in which the human figure opens up further levels of interpretation. Six decades later, Fijałkowski used abstract images to create empty landscapes, which enable the viewer to project their own fantasies and states of mind. Against this wide background, Musiałczyk created an intermediate realm using elements of figurative abstraction, in which the landscape bestows on the human form a dramatic, but transient state of the soul.

The dream of the lost suitcase

The founding of an independent art school in 1985, even before she finally settled in Hamburg-Volksdorf, gave Musiałczyk the prospect of fulfilment as well as a new goal in her life. From that time on, she not only built “a bridge to art” for children and adolescents, but also for adults, some of whom attended her classes in drawing, painting and composition for up to two decades, while others started their artistic career there or were able to build on it.[65] “Good things only happen”, she used to tell them, “when you make mistakes, try things out, cross boundaries and are prepared to take risks. [...] The eye must learn to see accurately. The more you discover and explore, the more interesting the world will become”.[66]

From 1993, she depicted human figures which were now no longer psychologically frozen and crammed between a mass of earth and walls of rock, but who were on the move. These figures set off and arrived separately or together, met each other along the way, swayed and teetered uncertainly between here and there, moved into rented rooms and finally had to learn to stand up for themselves in different situations and to communicate with each other.

In the series “Coming, Becoming, Going”, (Kommen, werden, gehen) (1993, Fig. 32-39, 42), the artist portrayed the drama of migration with abstracted outline figures, which with their simplification, elongated proportions and stiff movements looked like caricatures. People walk alone, in pairs, as families or in groups, firmly bound to each other and dragging other people behind, with houses and towns in their shouldered baggage as the burden of their memories. They pull carts behind them containing houses and ill people, on winding paths through empty landscapes. Once they have arrived somewhere, they are consumed by exhaustion and depression in the black night, while others – similar to Munch’s “Dance of Life”[67], which takes place on a beach before a sunset – dance in the background on an open stage (1998, Fig. 58). Klinger’s contemplative “Penelope”,[68] who night after night weaves a death shroud before a picture of Paradise during the odyssey of her husband Odysseus, could have served as an inspiration.

People meet each other along the way who face each other in a dynamic and emotional confrontation, and who become intertwined spiritually and emotionally. The series of the same name, “Meetings on the Road” (Begegnungen Unterwegs), consisting of black-and-white and colour drawings, was created in three stages, in different years: 1995/96, 1998–2000 and 2011–2013. There are pairs with a man and a woman, the wheels of their flight strapped under their feet, in silent confrontation: with the burden of the houses and towns of their memories (Fig. 1), naked and head-over-heels, separated by houses (Fig. 60), or opposite each other, yet separated by the house that they took with them on their journey on foot (all 1995, Fig. 69). They juggle with their wheels, as though still trying to decide what they feel about their own journey (both 1996, Fig. 67, 68).

Lovers, connected by a thin strip, sit back to back (Fig. 23), are entwined and assess each other eye to eye (Fig. 52), or are each separately searching for their own direction (all 1998, Fig. 53). For Musiałczyk, the “dance of life” becomes a celebration of the corporeal, which connects all people in love and in ongoing growth, as well as in pain, anxiety and disintegration (1999/2000, Fig. 18–20). From this celebration, the woman – always the central figure in Musiałczyk’s portrayal of life – emerges as Judith with the head of Holofernes, in other words, as the conqueror of evil, or, as the embodiment of female cruelty, as Salome with the head of John the Baptist (all 2000, Fig. 62). Love and happiness appear reduced to peasant roughness (2011, Fig. 50), plagued by a heavy burden of memory (2012, Fig. 51) and petrified in endless loneliness, in which each and every individual remains rigidly motionless in their own dreams (2013, Fig. 21).

Other series from the 1990s and 2000s focus on the fluctuation between different emotional states, as in the drawings from “It Teeters”, between staying and leaving in times of war, destruction and disintegration (Fig. 40, 41), between times in which one loses the ground from under one’s feet (all 1995, Fig. 54, 59), a final scream (1996, Fig. 44) and situations in which one becomes entangled in contradictory feelings (2000/01, Fig. 31, 30). The series “From Here to There” (Von hier bis dort) (1996, Fig. 56, 57), “On the Road” (Unterwegs) (1996-98, Fig. 5, 6, 63), “Journeys” (Auf Reisen) (2000, Fig. 61) and “Together” (Zusammen) (2000, Fig. 27–29) show the walking figures alone, in groups and as couples, crammed into narrow spaces, entwined or in a fight against each other. During their “departure”, they flee in the “ornament of the mass” (Siegfried Kracauer) or in a never-ending confrontation with obstacles (2000, Fig. 17, 45–49, 85).

In her series, which she produced from 1981 onwards, Musiałczyk reflects her own experience in drawn and painted parables, which attain universal relevance through the stylistic techniques of New Figuration, as well as through references to literature, mythology, and art history. High compositional, graphic and colouristic quality create a narrative plane that enables the image scenes to be read beyond their biographical origins – such as when the artist restricts the movement of the figures using the confines of the paper format (Fig. 53), creates drama through chaotic strokes of the pen (Fig. 40), or using a particular type of sfumato technique, characterises interrelationships among the figures or between the figures and the outside world (Fig. 28).

In 1998, Wojciech Leder referred to this universal plane in his essay: “The works by my teacher are an expression of an unusually subjective truth, which is, however, shared by many people. [...] These pictures are a lonely way of handling [...] time, which is dominated by a longing for past places, past people [...]. [...] The intimacy and sincerity seeps through from sensitivity to sensitivity – almost a tender whisper”.[69] The Polish writer and essayist Janusz Rudnicki, who has lived in Hamburg since 1983, was reminded of his own experiences: “Something made me stop and think with your works, however. The central train station in the 1960s, I was ten years old, after 3 o’clock in the afternoon, day after day. I am waiting for the train, for mother, like I did every day, she came by train from work. A stream of cloned, grey, hunched people flows out of the train. As though they had just exited from a cave. From the cave to home, their daily march. Not going towards anything, just around in a circle. [...] It tormented me: where have I seen these human-like figures before? [...] Do you know what it is? Chromosomes. [...] Cyclical transformations, long chains, don’t you feel at home there?”[70]

Musiałczyk has an affinity with Polish poster art, which from the 1950s onwards was also visible in exhibitions and publications in the Federal Republic of Germany, and which has also been on display in public and private collections since that time.[71] During the early post-war period, Polish artists developed a new aesthetic for film, theatre, opera, and exhibition posters. Here, in contrast to Hollywood posters, the themes were not directly transferred into imagery, but were encoded in abstract or expressive symbols and figures.[72] While during the 1960s and towards the beginning of the 1970s, coloured designs with doll-like motifs were predominant, the pictorial world became darker towards the end of the 1970s and during the 1980s and 1990s. Now, the designs were dominated by immobile faces and destroyed physiognomies. Faces pressed into boxes, like those we find in Musiałczyk’s drawings and paintings, are also depicted in posters by Wiktor Sadowski, while bandaged and fully bound physiognomies can be seen in the work of Andrzej Pągowski. The screaming, unlocked mouth from Musiałczyk’s series “It Teeters” (Es taumelt) (1996, Fig. 44), which is of course also recognisable as the motif by Munch, was also used previously by Krzysztof Bednarski, Wiesław Wałkuski, and Pągowski. Conversely, among numerous artists such as Stasys Eidrigevičius, Jerzy Czerniawski, Sadowski, Leszek Żebrowski and Mieczysław Górowski, the separated, immobile faces from Musiałczyk’s “Seeing Stones” (Schauende Steine) series became a real standard motif from 1985 until into the 2000s.[73]

However, Musiałczyk’s figural scenes are not just full of melancholy and sadness, as is often claimed.[74] Her figures allow us to get close, and rather than being permanently separated through conflicts and fighting, are eternally connected to each other. Individual figures emerge from the mass and go their own way. “I look at your small drawings and suddenly see”, Piotr eL wrote from Częstochowa in 1998, “that here there is also something new that gives reassurance”.[75]

At first, in the early 2000s, during her travels between Hamburg and Łódź, during which she took dozens of photographs from the moving train for new artists’ books, Musiałczyk was still impatient: “run to you / run and run / trees flicker past / [...] wheels throb / fields forests / cites towns / run and run” (renne zu dir / renne und renne / bäume flackern vorbei / […] räder pochen / fluren wälder / städte städtchen / renne und renne)”.[76] A decade later, the fear of not only having lost important travel items, but also the memories on one of these journeys, turned out to be no more than a bad dream, linked to the certainty that not everything had been lost, after all. “dream of a lost suitcase / of forgotten treasures / of walking on a muddy path / of searching for far-away places / [...] where once I was / where my baggage remains” (“traum von verlorenem koffer / von vergessenen schätzen / vom wandern auf schlammigem weg / vom suchen entlegener orte / […] wo einst ich schon war / wo mein gepäck harrt”).[77]

From 2000–2007, under the collective title “Episodes” (Episoden), (Fig. 88–92) Musiałczyk produced several series of small-format colour picture stories, in which she portrayed the psychological and spiritual entanglement of individuals, relationships between couples and one time also triangular relationships. On that day, she wrote in 2005, a small picture was produced which fulfilled the desire “to wrest individual scenes from the flow of events and from the uniformity in which they become lost”.[78] Experienced in the analysis of psychological states, she now dedicated herself, with precise observation and in the style of pictorial satire, to the human relationships and activities that are to be found in everyday life. In an over-exaggerated way that is never deadly serious, she reduces figures to a single body part, restricts couples to an outline and extends limbs to act as brackets to make clear that we are all connected to each other, and that only in exceptional cases does any one of us exist for him or herself alone. Piotr eL wrote: “In her work, I find something that frightens, but that also discretely soothes: Janina sees painfully clearly what shames and aggrieves, yet this clarity is mitigated by the heartfelt warmth of her view onto the small private dramas that make up the life of each and every one of us”.[79]

Under the shadow of the migration crisis between Belarus and the European Union in August 2021, during which ten migrants died when refugees from Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries were forced to remain in the border territory between Belarus and Poland, Musiałczyk began a new series of drawings and paintings under the working title “Flight – Refuge” (Flucht – Zuflucht), which also referenced her own story of flight. With the plan to use the images, which were constantly updated on public and social media, “with the aid of traditional techniques and small formats”, to create “space – and at the same time provide refuge – for a very different testimony; the silent, intimate expression not influenced by discourse”,[80] she produced works on dark, pre-dyed paper with coloured drawing inks, white and black Indian ink, wooden quills, coloured pencils, felt-tip pens and paint pens, and combined them with monotype and the stamping technique she had used earlier. Acrylic images were created on dark, pre-dyed canvases and tinted paper. That same year, in order to then produce an artist’s book using some of these works, which was entitled “I Don’t See It, so It Isn’t There” (Seh nicht, also ist nicht / Nie widzę, więc nie ma), Musiałczyk received a “Hamburg future stipend for the fine arts and literature” awarded by the Hamburg Ministry of Culture and Media (Hamburger Kulturbehörde) in collaboration with the Hamburg Culture Foundation (Hamburgische Kulturstiftung) and the Hamburg professional artists’ association (BBK Hamburg).

The fold-out double pages of the artist’s book, which was published in 2022, show people beating their way through deep forests, pushing on through undergrowth and grassland, standing in front of fences and screaming for help, and finally, emerging from the darkness (Fig. 93–99). However, their situation is not hopeless: finally, at the end of the book, a few of them step into a field of light blue. In summary, Piotr eL wrote: “... what a horribly painful scream. [...] ... the sublimated hypostasis of a drastic observation – in other words, what the purpose of art can also be”.[81]

The title of this, the artist’s most recent book, “I Don't See It, so It Isn’t There” (Nie widzę, więc nie ma / Seh nicht, also ist nicht)[82], in which the viewing slits between the folded-in double pages offer the reader a glimpse onto the drama that is taking place behind them, could also be the motto for Janina Musiałczyk’s work overall: events can only persist in reality when we do not close our eyes to them. Only that which is made visible, if only through art, can exist. That to which we close our eyes is in danger of being forgotten.

Axel Feuß, October 2023

Voices of people who have accompanied the artist on her journey:

The search for the perfect composition

Janina Musiałczyk, or INKA to us. 20 years ago, I received the small artist’s book from Inka, “Drawings and Texts” (Zeichnungen und Texte), with reduced, almost dry, short texts about her journey from Poland to Hamburg. When I read them, I cried, I just cried. I couldn’t control myself. With her minimalistic techniques, Inka has succeeded in tackling a serious issue, MIGRATION, on a very profound level. I have read this small book again several times, and again, I have cried.

Of course, there are beautiful, balanced, colourful areas in Inka’s paintings. You can feel an incredible consistency and stubbornness in her search for the perfect composition. Yes, as a painter, I am always rather jealous of the way Inka works with colours. With Inka, you can feel a great love of colour and great respect for painting, and at the same time, a modesty in her relationship with art. Perhaps she learned this from her professor in Łódź, Stanisław Fijałkowski.

Wiesław Smętek, illustrator, painter, drawer and friend of Janina Musiałczyk. Seevetal, 2023

Art teacher in Łódź

I was eight years old when my father took me to an art class given by an unusual woman, who every week for the next ten particularly formative years would exert an incredible influence over me. For forty more years, we continued to meet, both in letters and in a more fleeting exchange of ideas.

Piotr eL. Częstochowa, 2023

Art teacher and wonderful human being

Inka Musiałczyk is one of the most important people in my life, to whom I have much to be grateful for. I already inherited an interest in and affinity towards art from my parents in Poland. At an age which shaped me as a person and which presented me with decisions about my further course in life, namely as a 16- or 17-year-old, I ended up in the art class run by Inka Musiałczyk. There, I was lucky to get to know not only the outstanding artist, but also a wonderful person. After a break lasting several years, which was interrupted only by the occasional letter, I was able to meet Inka again in Germany, where I have lived for years and where I work as a paper restorer. The relationship between teacher and pupil became a close friendship. Inka not only enriches my life with her art, which I value highly, but she is always ready to listen and, when necessary, gives good advice.

Krzysztof Nast M.A., restorer. Kleve, 2023

“For us, she embodied the world of art”

The Palace of Youth (Pałac Młodzieży) in Łódź, housed in a beautiful modernist building in the centre of the city, contained a large number of creative workspaces, including an atelier for the fine arts, run by Janina Musiałczyk.

It was a place of artistic initiation and inspiration, as well as a place to meet other people of my own age with similar sensibilities. Some of us remained friends for life.

Our initiation into art included drawings, simple graphic techniques such as monotype, and, only later, painting from watercolour through to the long-desired challenge: oil colours and painting at an easel on a canvas. Sensual, secretive names of colours on the palette: ultramarine, Paris blue, Egyptian blue, ochre, umbra, satin ochre, Veronese green ... Concepts and basic knowledge of image composition, expressing ideas through symbols, and graphic drawing for posters, realism of visualisation and abstract thinking. Study trips, discussions about art, a feeling of belonging to an extraordinary place. These attempts took place under the custody of Janina Musiałczyk, Inka. Beautiful, friendly, clever, stylish like a whisper of artistic perfection. We worshipped her. For us, she embodied the world of art towards which we strove. It was she who had created the atmosphere in this powerful, influential workshop. Above all, she was an inspired teacher. Later, she gave us, a group of her students, her friendship.

I only really became acquainted with Janina Musiałczyk’s work later on, and it surprised me. There was no superficial aesthetic, although in her paintings, there are beautiful, subtle compositions rendered in carefully selected colours.

It is existential art, candid, intimate, at times almost painful. The record of a journey on foot, indeed of the wandering to and fro with no clear sense of direction, the lack of rootedness, as reflected by the titles of her works – such as “Coming, Becoming, Going” (Kommen, werden, gehen). The motif of the house borne on one’s back or on wheels, one’s entire world packed into a suitcase, on a cart, in a bundle, the cipher of the house, which needs to be furnished again and again, on the road, in “rented rooms”, in the search for a new mooring.

Drawings that express the imbroglios with the other, for better or for worse, in love and conflict, entanglements, the head carried on the back like a hump of sorrow, meetings and separations along the road. Emotions captured in brief dramas, like short theatre scenes.

I especially like the drawn (self-)portraits, where a second face appears on the ribcage or on the stomach, like an inner child furtively observing the world outside, or an inner observer that has been awakened.

For this existential, secular meditation, Janina Musiałczyk has found a raw, simplified form that sharpens one’s observation, and allows what is observed to come more sharply to the fore. The courage to be candid, the courage to show the inner, internal world in all its existential struggle, is what makes this art so extraordinarily valuable. She is a mirror that reflects back the universal fate that we all share.

Małgorzata Misiowiec, graphic designer. Łódź, 2023

As a teacher and mentor in Hamburg

Meeting with fate: My approach to painting, drawing and composition was expanded in the deepest sense by Janina Musiałczyk, and even today is still accompanied by her own empathetic capability.

Rosemarie Burmeister, student adviser, writer and painter. Hamburg, 2023

“Trust in our capabilities”

Our teacher Janina: giving us tasks that gave us the greatest possible freedom as to how we completed them; individual, empathetic instruction and support, borne by the sincere, passionate desire that we find our way to our own expression and style; an infectious trust in our ability. I have learned a great deal from Janina the person and the artist, and also about myself, and I will always be grateful to her.

Remda Saborowski, student of drawing, painting and composition at the art school run by Janina Musiałczyk 1990–2008. Wedel near Hamburg, 2023

A bridge to art

Janina Musiałczyk is one of my most important teachers. She built a bridge for me to art, which had been lacking in my study of visual communication. As a teacher, she was always inspiring and very precise in her observations. I still hear her voice when I am working. Also her “just keep going” when things weren't working out so well. She was always generous with her knowledge and contacts, and gave us insights into her work and life. Her view of the world expanded my own, and without doubt, her style, especially in drawing, was a big influence on me.

Silke Storjohann, freelance photographer. Hamburg, 2023

“Years spent together”

I was never a student of Janina Musiałczyk’s. And yet our many years together, through friendship and our artistic work, have influenced and instructed me. Her profound works have always touched me so deeply that I am lost for words when I stand in front of the tender, yet so strong strokes in her graphic images. She is and always was consistent and positively strict, and she loved her homeland. The themes of a “person filled with feeling”, so heartfelt, so profound, sometimes achingly sad, and yet so human ... simply wonderful! We are cousins; her mother and my father were siblings. We didn’t become close until adulthood, yet we gained our sense of connection through art, through her art.

Agata Schubert-Hauck, artist. Berlin, 2023

Memories of Janina Musiałczyk from Paris

If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man,

then wherever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you,

for Paris is a moveable feast.[83]

If you were lucky enough to have met Inka as a young person,

then wherever you go for the rest of your life, she will stay with you,

like a moveable feast.

In the magical, winding lanes of the moveable feast, anything is possible. In magical places, the past sometimes turns into this afternoon. And although fleetingly, it has its form, its shape and its size. These are bounded by time and place. Yet memories have their power, their colour tone, their rhythm of appearing and suddenly disappearing. While I was looking out at the Place de la Contrescarpe from the restaurant Le Volcan in Paris, I observed the shadow of Ernest Hemingway’s steps moving towards his apartment.[84] You could hear his conversation with Gertrude Stein borne on the wind. Another whisper, a small, quiet voice on the breeze, this time from the Santiago du Chili park[85].

I heard, barely audible: Please draw me a sheep.[86]

Suddenly, I heard the following words, somewhat louder: Please record memories.

I stood up. Looked around. Tried to make out where the request came from. Pedestrians walked hurriedly or slowly, sometimes lost in thought, past the tables, which at this hour were still empty.

Mindful of Herbert’s advice, I did not return to the table: Everything that you do at the table, you do coolly and matter-of-factly.[87] Therefore, I did not sit back down. You do not record memories in a cool, matter-of-fact way.

Inka’s magical classes on experiencing art are still alive within us, and if we look around more carefully, we become aware that they still accompany us today. And at times even hurry on ahead of us. Only later do we become conscious of the fact that the steps we took afterwards were also guided by Inka, even at times when she was far away.

She was a friend of extraordinary authority, not just in terms of the master-student relationship. With a tender smile, she showed us the way without expressly describing it to us. She allowed us to make our own choices and interpretations. She expected us to make independent decisions. With her warm voice, she alleviated resistance and failures, waited patiently until we had achieved our goal.

We had to grow up quickly in order to follow this instruction and to understand what it meant. Ever so often, it is enough to close our eyes to be able to see – and to concentrate in order to feel the magic of the art.

It was the most wonderful lesson in the discovery of

shifts of mood, which are hidden in art.

It was a moveable feast.

Prof. dr hab. inż. arch. Marek Pabich, head of the department for drawing, painting and sculpture, Director of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Planning, Łódź Technical University (Politechnika Łódzka), 2023