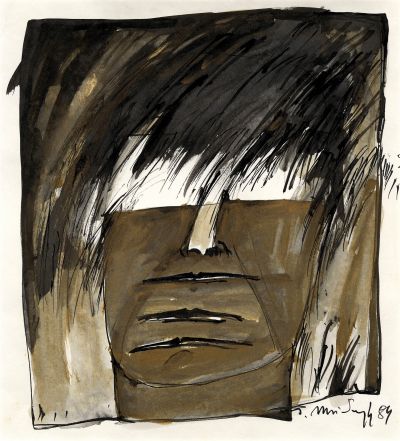

Janina Musiałczyk. W drodze, on the road

Mediathek Sorted

However, Musiałczyk’s subjects don’t just herald “something ominous, an antagonism, a polarity that is impossible to overcome, an evil ending” (Klemm). In her series “Rented Rooms” (Mieträume), which she produced from the mid-1990s onwards as ink drawings and canvas paintings using different techniques, more conciliatory pastel tones dominate, which generate diffuse moods. In grid-like structures reminiscent of high-rise estates, figures, which look statically in different directions, come to rest.[16] At the same time, the people are arranged systematically in rows and are locked in box-like cells. The houses into which they boldly march in are new, with roofs, although it appears that escape from them is impossible (2002, Fig. 86). In dark moments, these “rented rooms” (1998, Fig. 43) seem like a lonely epicentre in a swirling maelstrom of life, which transforms the ecstatic joy of existence depicted by Henri Matisse[17] into the horror of never-ending isolation, as expressed by Edvard Munch in his paintings and graphic art.[18]

The series “For the Boy” (Für den Jungen) (1998–2000, Fig. 75–77) strikes a more conciliatory note. Musiałczyk created a house to live in and a protecting family for an isolated, lonely boy she discovered in a photo album. In the later series, “Ghosts and Houses” (Geister und Häuser) (2015, Fig. 64–66), the dread she herself felt as a child comes to the fore: Musiałczyk recalls that in 1948, “In the evening, before I go to sleep, I move the furniture, push it around like wooden blocks. It’s enough to push the sideboard out into the middle of the room, and there, behind it, I have my space”.[19] Her fear of houses and indoor spaces which are home to the ghosts of the past where the horrors of the present reside, are also reminiscent of the pictorial themes of Edvard Munch.[20]

Surrealist artists such as René Magritte, Paul Delvaux and Giorgio de Chirico turned abandoned buildings and interior spaces into background scenes of frightening, dream-like worlds that floated between life and death. In these spaces, day and night, the internal and external worlds,[21] past and present times,[22] merged with each other. Time stands still,[23] or terrifying events from childhood are invoked.[24] For the Hamburg art journalist Evelyn Preuß, Musiałczyk’s subjects are a “variant of Polish Surrealism”, suffused with a depth of feeling.[25] Wolfgang Till Busse, an art historian from Cologne, notices a “particularly poetic-surreal pitch”, which has its origins in an unconscious experience that has not been intercepted by external influences, when “the hand moves as of its own accord. In so doing, she uses the écriture automatique technique developed by the Surrealists during the 1920s”.[26]

The writer Franz Kafka developed an obsession with interior spaces and dwelling places. He found his parents’ apartment in Prague oppressive and frightening, and fled from there to Berlin in 1923 when he was severely ill in order to create a home of his own with his new life companion, Dora Diamant. Torn between a liberating idyll and financial hardship, he was forced to repeatedly search for new places to live there, too, until his illness prevented him from leaving his final abode. In his novels and novellas, he had already described a rented apartment on a suburban street in a remote town in North America as a prison ruled over by a prostitute.[27] There are attic rooms branching out in all directions, with lawyers’ offices and interrogation rooms; a boundary experience of human existence and the precursor to execution.[28] It is no coincidence that the metamorphosis of Gregor Samsa into an insect takes place in the room of Samsa’s parents’ apartment.[29] For Kafka, the rooms where he lived in Berlin also became places of terror. He and Dora were forced to leave their first home by the unfriendly behaviour of their unsympathetic landlady,[30] and the last place where they lived reminded him of an underground, labyrinthine badger’s burrow, in which sounds of digging brought on feelings of paranoia.[31]

Musiałczyk found paths to reconciliation. In one of her poems, which she wrote between 2001 and 2014 after travelling between Hamburg and Łódź, she recognised that the “shadow on the wall / around the door / has perhaps always / been here / has two legs / and two arms” (“schatten an der wand / um die tür / vielleicht immer / hier schon gewesen / hat zwei beine / und zwei arme”) – that the shadow disappeared at night and returned in the morning. The phantom, which was only visible in daylight, was nothing more than an image of herself: “shadows on the wall / head all / tousled” (“schatten an der wand / kopf ganz / zerzaust”).[32] In the paintings of the “Steps” (Stufen) series (2006–19, Fig. 79–83, 87), which she produced during the same period, she shows houses which, reduced to basic geometric shapes, exude security and joy of life with their bright, even glowing, colours. In an interview given in 2015 on the occasion of her exhibition “When searching for form, I find the anecdote” (Szukając formy znajduję anegdotę at the Galeria Nieformalna in Warsaw, she claimed that: “The four walls are important – safe and silent. No noise from the outside world penetrates them”.[33] Later, she said that for her, a real home means “Safety. Independence. [...] One has more space for oneself, and calm from the turbulence of the world”. However, the search for this place is “often a burden and a difficult path”.[34]

[16] From the series “Rented Rooms” (Mieträume), 1995, acrylic, pencils, stamp on canvas, 54 x 65 cm; from the series “Rented Rooms” 1995, acrylic, pencils, stamp on canvas, 40 x 50 cm; from the series “Rented Rooms”, 1997, acrylic, collage on canvas, 50 x 60 cm; from the series “Rented Rooms”, 1997, acrylic, collage on canvas, 60 x 80 cm; all in: Zeichnungen und Bilder 1998 (see note 11), No. 11–14, 16.

[17] Henri Matisse: “Dance (I)”, 1909, oil on canvas, 259.7 x 390.1 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

[18] See e.g. Edvard Munch: “The Dance of Life”, 1925, oil on canvas, 143 x 208 cm, Munch-museet, Oslo.

[19] Zeichnungen und Texte 2001 (see note 1), page 8.

[20] Edvard Munch: “Red, Wild Wine”, 1898–1900, oil on canvas, 119.5 x 121 cm, Munch-museet, Oslo; “Evening on Karl Johan Street”, 1892, oil on canvas, 84.5 x 121 cm, Bergen Kunstmuseum; “The Storm”, 1893, oil on canvas, 92 x 131 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York; “Death in the Sickroom”, approx. 1893, tempera and colour pencil on canvas, 152.5 x 169.5 cm, Nationalmuseum Oslo; “Jealousy”, 1907, oil on canvas, 57.5 x 84.5 cm, Munch-museet, Oslo.

[21] René Magritte: “The Empire of the Lights” (L'empire des lumières), 1954, oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels; “The Key of the Fields” (La Clef des champs), 1936, oil on canvas, 80 x 60 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

[22] Paul Delvaux: “Sunset over the City” (L’aube sur la ville), 1940, oil on canvas, 175 x 202 cm, Belfius Art Collection, Brussels.

[23] René Magritte: “Time Transfixed” (La Durée poignardée), 1938, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago.

[24] Giorgio de Chirico: “Mystery and Melancholy of a Street” (Mistero e malinconia di una strada), 1914, oil on canvas, 87 x 71.5 cm, private collection.

[25] Evelyn Preuß: Aus Wiesen schauen Gesichter. Janina Musiałczyks Bilder behandeln Seelenzustände, in: “Hamburger Abendblatt”, 19.5.1988.

[26] Wolfgang Till Busse: Ungebeten. Agata Schubert-Hauck & Janina Musiałczyk, opening speech in the Galerie Kunstraub99, Cologne, on 14.1.2016.

[27] Franz Kafka: America (Amerika – Ein Asyl), 1911–14.

[28] Franz Kafka: The Trial (Der Prozess), 1914/15.

[29] Franz Kafka: Metamorphosis (Die Verwandlung), 1912.

[30] Franz Kafka: A Little Woman (Eine kleine Frau), 1923.

[31] Franz Kafka: The Burrow (Der Bau), 1923.

[32] schatten an der wand ..., 5. April 2006, in Janina Musiałczyk: w drodze_unterwegs (W DRODZE_trzy zeszyty – UNTERWEGS_drei hefte, Heft 2), self-published, Hamburg 2015.

[33] Porysować cały świat (Drawing the Whole World), Janina Musiałczyk in conversation with Stanisław Gieżyński, in: Weranda. Najpiekniejsze polskie domy, rezydencje, ogrody i sztuka, No. 11/155, November 2015, page 50.

[34] Conversation during the visit of fashion designer and freelance editor Larissa Wasserziehr. See: Zu Besuch bei Künstlerin Janina Musialczyk (On the Visit to Artist Janina Musialczyk), 12 May 2019, at https://derblauedistelfink.de/zu-besuch-bei-kuenstlerin-janina-musialczyk/ (last accessed on 25.10.2023).