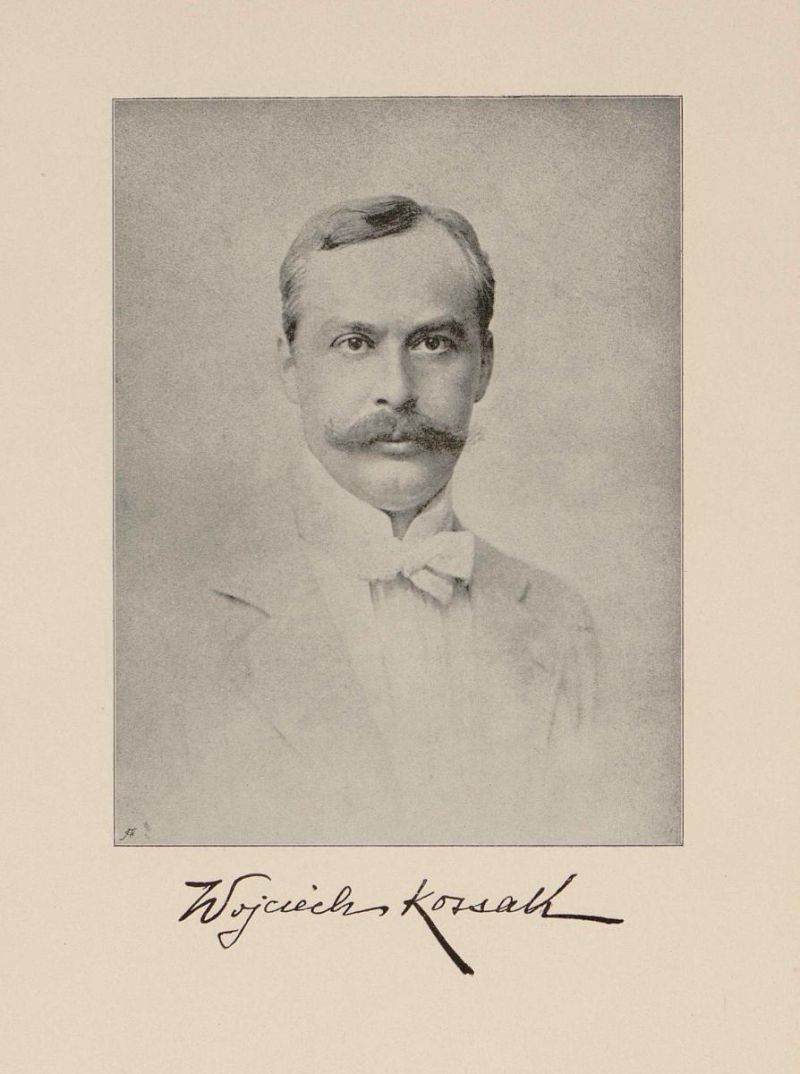

Wojciech Kossak: Memoirs, 1913

In August 1900 Kossak received a court telegram from the Emperor ordering him to travel to Naples, from where he was to go to China as a war painter in the staff of Field Marshal Alfred Graf von Waldersee (1832-1904). On 27th July, an international expeditionary corps had left Bremerhaven to quell the Boxer Rebellion in China. Kossak had just signed a contract for a panorama of the "Battle of the Pyramids" and wanted to travel to Egypt to prepare it. At the last moment, he succeeded in averting the assignment thanks to a personal conversation with the emperor during a cavalry inspection in Altengrabow, to which he had also been ordered. The battle painter Theodor Rocholl (1854-1933) travelled to China in his place (p. 172-175).

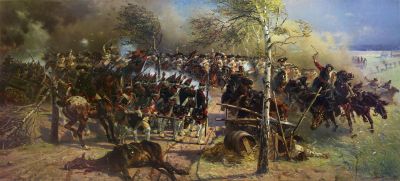

Kossak then accepted another commission, that of a consortium founded in Warsaw to create a new panorama showing the Battle of Somosierra on 30th November 1808, as Kossak reports in the eponymous chapter. Other national-Polish subjects had previously been ruled out because they would not have passed the Prussian censorship. On the other hand, the battle of Somosierra, in which Napoleon had defeated Spanish troops on the mountain pass 60 miles north of Madrid and then fought his way to the Spanish capital with the substantial participation of Polish cavalrymen, could be considered as an innocuous topic of pan-European significance. Kossak was guaranteed a sum of 100,000 roubles for the production of the panoramic painting and the sculptural foreground terrain. It is interesting to note that in the general context of battle painting, Kossak admitted that previous paintings on this theme by French and Polish painters like Vernet, Suchodolski, his father and himself had been pure "fantasy creations" in terms of the landscape and the battle terrain. For the new panorama, however, it would have been essential to create as faithful a representation as possible. In this case also, Kossak not only studied historical literature, but also consulted a proven military historian, the Russian infantry general Aleksandr Puzyriewski (1845-1904) (p. 179-181), who came from Lithuania.

After taking a holiday with the Emperor, Kossak and his colleague Wywiórski travelled by train via Paris, Bordeaux and Madrid to Segovia, then on to the Castilian foothills in an "omnibus" pulled by mules. From there they travelled on foot to the mountain pass in question equipped with permits from the Austrian embassy, a local guide and a two-wheeled cart pulled by mules, carrying painting utensils and photographic equipment. The author describes in detail the battlefield and other geographical details known from the historical writings. These were captured by the painters in sketches and photographs (p. 181-202), including the associated troop formations.

Despite the Emperor's benevolent assessment of the first drafts created in Monbijou Castle, the Somosierra panorama was threatened with remaining unfulfilled. Kossak travelled to Warsaw with four sketches on a scale of 1:10, where the work was approved by the consortium and the military historian Puzyriewski. The latter agreed to work with the Russian Governor General of Warsaw, Alexander Imeretynski (1837-1900), to exhibit the future panorama in Warsaw. But Imeretinski refused, as he apparently feared nationalist Polish riots, as can be read between the lines in the chapter entitled "Prince Imeretynski and Grand Duke Vladimir" (p. 205-217). In view of the financial loss incurred by the Panorama building that had already been rented in Warsaw, and the canvas ordered in Brussels, Kossak appealed for mediation to Wilhelm II, who in turn contacted Grand Duke Vladimir Romanov, son of Tsar Alexander II, the man responsible for artistic affairs in Russia. Finally Kossak himself travelled with his designs to St. Petersburg to lend emphasis to the Emperor's despatch. But not even Grand Duke Vladimir was able to persuade Imeretynski to change his mind. In the meantime, in Berlin Kossak had completed the "Battle of Zorndorf" and a portrait of the Emperor on horseback, for which he was personally awarded the Order of the Red Eagle by the Emperor, after having received the Order of the Royal Crown six months earlier (p. 208).

Kossak dedicates three chapters totalling 45 pages, "Stuttgart – Kaisermanöver – Franz Joseph I. in Berlin", "Stettin" und "Des Kaisers ‚Rache‘", to his participation in manoeuvres of the Prussian army under the leadership of Wilhelm II. Due to his membership in the Austrian army he held the title of a "military attaché of foreign powers". As a guest of the Emperor he had a court equipage, a service horse and an orderly at his disposal, stayed in the best hotels and participated in the meals of the diplomatic corps (p. 219 f.). Foreign officers and diplomats were admitted to the manoeuvres as observers, but excluded from the demonstration of new means of transport and guns. On the battlefield he was regularly summoned to the Emperor (" Herr von Kossak, please report to his Majesty") in order to view particularly "picturesque" battle orders from his vantage point (p. 224).