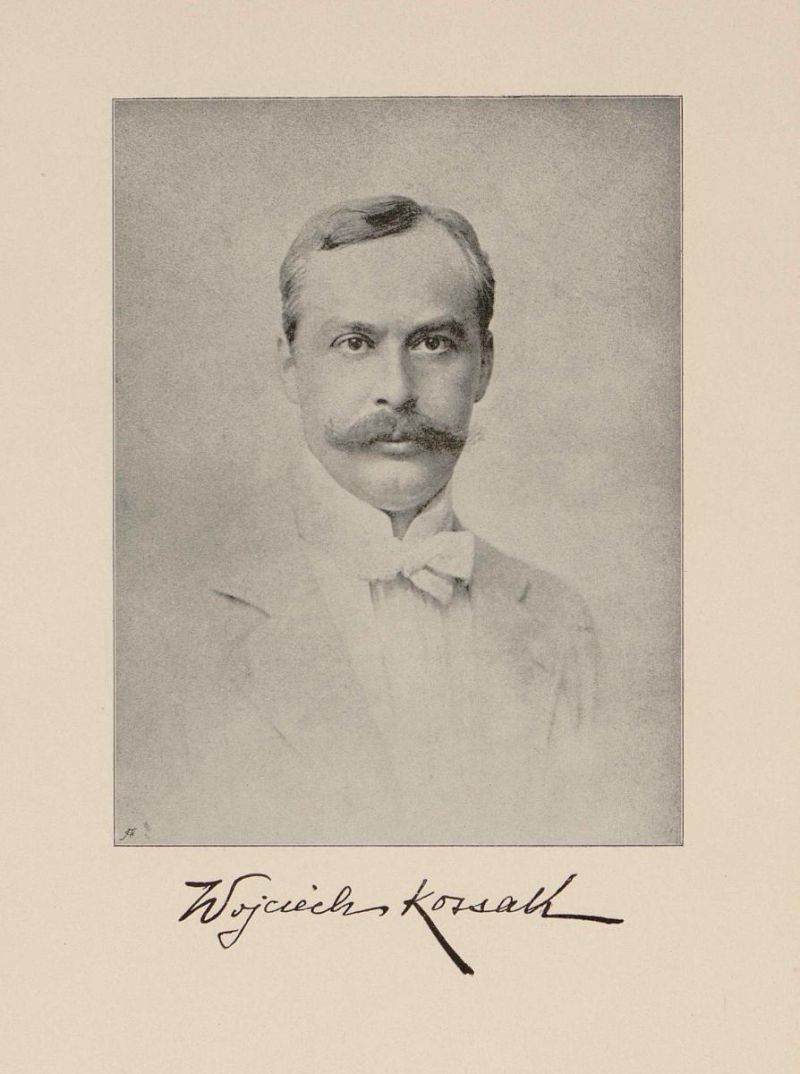

Wojciech Kossak: Memoirs, 1913

In contrast to the Polish edition (see PDF 1) the German edition appeared without the illustration on the binding, but as a half leather volume with marbled book covers and leather corners (see PDF 2).[1] With the exception of a few changes in the chapter structure, the two editions appear to differ only slightly. They are illustrated throughout with 92 (90) black-and-white illustrations, namely contemporary photographs, reproductions of paintings, as far as they belong to the textual context, and watercolours and sketches created especially for the book, as well as with 8 (9) colour plates again based on oil paintings by the artist. Both editions are dedicated to his mother, Sophie von Kossak/Zofia z Gałczeńskich Juliuszowa Kossakowa, and to his wife, Marie von Kossak/Marya z Kisielnickich Wojciechowa Kossakowa, "the two Polish ladies who knew how to be women artists. Today the volumes are available in at least one hundred libraries worldwide.r.[2] The manuscript can be found in the National Library/Biblioteka Narodowa in Warsaw in the Wojciech-Kossak-Archive/Archiwum Wojciecha Kossaka.[3]

Wojciech Kossak[4] was born on New Year's Eve 1856 in Paris, his twin brother Tadeusz (1857-1935) shortly thereafter in the New Year. During his law studies in Lviv his father, Juliusz Kossak (1824-1899), had studied painting at the private painting school owned by the portrait and genre painter Jan Maszkowski (1793-1865), and had already become a portrait, hunting and horse painter at a young age. After his marriage he went to Paris in 1855, where he studied museum collections, maintained close relations with the battle painter Horace Vernet (1789-1863), worked with a group of Polish painters led by Wojciech Gerson (1831-1901) and where his sons Wojciech, Tadeusz and Stefan were born. From 1861 to 1868 Juliusz Kossak was the artistic director of the magazine Tygodnik Illustrowany in Warsaw. In 1868/69 he resumed his studies in Munich for about ten months in the private studio of the battle painter Franz Adam (1815-1868), where he had intensive contact with the Polish painters Józef Brandt (1841-1915) and the brothers Aleksander (1850-1901) and Maksymilian Gierymski (1846-1874). Back in Poland he settled with his family in Krakow and became known as a painter of historical and battle scenes, a watercolourist and illustrator.[5]

Horace Vernet became Wojciech's mentor, "a kind of kinship between two painter dynasties that is still unique in art history," as Kossak writes (German edition, p. 3). His earliest memoirs are dedicated to the soldiers on the forecourt of the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris, where war-wounded soldiers, illustrated in a painting from 1912, are looking into the pram of the little Wojciech and posing with his Masurian nanny (Fig. 1). His father had contacts with old Polish politicians who had emigrated to France, and officers of the Polish army like Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski (1770-1861), head of the Polish revolutionary government of 1830, and General Władysław Zamoyski (1803-1868), his close confidante. For the father, "these long-gone types of soldiers were an inexhaustible source of study" (p. 7), the stories of old gentlemen that he presumably recounted later. For the child, they were exciting episodes from the infernal world of war.

The start of the "childhood years in Warsaw 1863-1866" for the five-year-old was marked by crowds of wild horsemen wearing huge fur caps, scimitars and long pistols. During the January Uprising, they galloped past the balcony of his parental home from Neue-Welt-Straße/ul. Nowy Świat to the suburbs of Krakow/Krakowskie Przedmieście (p. 24), a scene that Kossak illustrates in watercolours that he also painted in 1912 (Fig. 2). The twins narrowly escaped a bomb attack on the Russian governor, Friedrich von Berg (1794-1874). Numerous relatives joined the uprising. There were denunciations and apartment searches, from which the Kossak family was not spared. Arrests, deportations of exiled persons and public executions soon became part of everyday life in Warsaw. At the grammar school, Wojciech sketched battles, horses and armed cavalry. When Russian was introduced as the official teaching language in 1867, the Kossaks moved to Krakow to have their children educated at Polish schools (p. 32).

The Krakow chapter takes the reader to the time of Wojciech's first studies at the Krakow School of Drawing and Painting/Szkoła Rysunku i Malarstwa, (from 1873 the School of Fine Arts/Szkola Sztuk Pięknych), which he attended after leaving grammar school at the age of fourteen with his father's permission. Under the guidance of the history painter and art historian Władysław Łuszczkiewicz (1828-1900), a man "without any artistic talent", as Kossak writes (p. 38), the young art student learned to draw and paint from male and female nude models and from nature. The atmosphere at the school was relaxed and cheerful. The young Polish "Bohème" students, whose parents did not live in Krakow, lived in dire poverty.

One year later Wojciech's father brought him to Munich for further training and placed him "under the guardianship of a whole Plejade" of older Polish artists like Maksymilian Gierymski, Józef Brandt, Stanisław Witkiewicz, Józef Chełmoński and Władysław Czachórski, as well as "lesser known, less famous" artists like Władysław Malecki, Ludwik Kurella, Antoni Kozakiewicz and Franciszek Streititt, who were "the most pleasant colleagues and comrades, free from any professional envy". In his Munich chapter Kossak also mentions younger Polish painters "who joined them after work": Alfred (Wierusz-)Kowalski, Henryk Piątkowski, Franciszek Kostrzewski, Stanisław Czachórski, Jan Rosen, Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz, Włodzimiersz Łoś, Wojciech Piechowski, Roman Szwoynicki, Antoni Piotrowski and Michał Pociecha. A "wonderful harmony" prevailed among them, "the older ones were sincerely kind towards the boys and the boys could feel it" (p. 41).[6]

Twice a day, according to Kossak, the artists met without exception for a coffee in Café Carlsthor, and in the evening for a game of billiards in Café Tambosi[7] The painter Josef/Józef Brandt was the main figure in the circle. At that time Munich art dealers were pushing motifs of the "Polish landscape" and these were sold in droves: "Anyone who could paint a flat horizon with a grey sky and a few wolves on it was sure to make a bargain, no matter what the work was like. "Enormous quantities" of such landscapes were exported to America. Many painters "secured material independence for the rest of their lives during these few golden years" (p. 42). He himself had scarcely left the Munich Academy of Arts where he had studied under Alexander Strähuber (1814-1882),[8] kand alternately drawn scenes from ancient mythology and, in evening classes, female and male nudes (p. 43). He experienced the working anniversary of the academy director Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874), which was celebrated by the student fraternities, as well as attending numerous opera performances and philharmonic concerts. Ultimately he left Munich "without the slightest regret, but enriched with technical knowledge" (p. 44).

A little more than the ten pages describing his artistic studies in Krakow and Munich are taken up by the section of Kossak's memoirs entitled "military service" in 1876/77. The reason for this is that they played a decisive role in the development of his "singularity as a painter". His portrayal of military service "with the Ulans, a genuine Polish Krakow regiment" is a homage to the "Polish cavalry of men and horses" (p. 47) and to a special type of Polish soldier: weather-beaten, full of energy and determination, with an attentive eye, straight back and the typical "Masurian moustache... the horse makes him lithe and agile" (p. 49). A detailed anecdote describes Kossak and his twin brother during drill and a demonstration of galloping, attacking and retreating - again illustrated with matching watercolours.

After one year of service, Kossak left for Paris in 1877 - the author seldom mentions concrete dates, and the reader is therefore forced to deduce them from the context - on the advice of his father, to complete his painting studies at the art schools of Léon Bonnat (1833-1922) and Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889). One of his first visits was to a friend of his father, Count Konstantin Branicki and his wife,[9] who had "made their home the meeting point of Polish circles", and invited a group of Polish exiles every day to morning tea, as well as distributing alms to petitioners. They also provided financial support to the Polish school of Batignolle, a project run by Brother Xavier, and to the Polish church in Paris, Notre-Dame de l'Assomption (p. 61 f.). Through the intervention of the Polish painter Henryk Rodakowski (1823-1894) Kossak met Bonnat, who accepted him into his private painting school. Anyone hoping to gain historical insights into Kossak's six years of studies in Paris will only find two anecdotes described in detail in the corresponding chapter. These are his admission as a newcomer to the school of painting (p. 64-67), accompanied by a variety of jokes, and the unsuccessful hanging of a portrait of a lady painted by Kossak in the Paris Salon (p. 69-74). Kossak's return from Paris to Krakow in 1884, his marriage, the opening of his own studio and the following nine years of artistic activity there are left unmentioned in the "Memoirs".

However, in the chapter entitled "Gödöllő" he reports on the first presentation of a pictorial motif in the Künstlerhaus in Vienna in 1886, which was based on his experiences during his military service (p. 77). The life-size painting of a bayonet attack by an infantry regiment with a mounted officer and a trumpeter on horseback, depicted in the book as a black and white plate (Fig. 3), aroused the interest of Emperor Franz Joseph I, who opened the exhibition and asked to get to know the painter of the picture during a tour. Kossak, in the uniform of a Ulan lieutenant, explained to the emperor his roots as the son of Juliusz Kossak, elucidated his military and artistic career and provided him with information about his painting. The purchase of the painting, which later hung in the Emperor's study in the Hermes villa in Lainz, led to an invitation to a par force hunt in Gödöllő, the royal Hungarian hunting residence north-east of Budapest. Of course Kossak, "being a thoroughbred Pole, the finest cavalry material from birth", made an excellent figure in the hunt and was heaped with praise by the Emperor (p. 89). Today, the page-long descriptions of hunting with horses and dogs will only be of interest to hunting historians and connoisseurs of the Danube Monarchy.

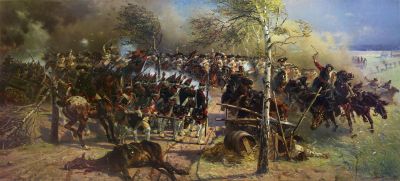

From 1893 Kossak worked alongside the Lviv painter Jan Styka (1858-1925) on the Panorama of the Battle of Racławice, which was presented to the public the following year at the National Exhibition in Lviv. The success of this panorama painting[10] moved the Polish painter Julian Fałat (1853-1929)[11], who had been living in Berlin since 1886 and worked for Emperor Wilhelm I, to offer Kossak the chance to work on another panorama painting. They jointly agreed on the theme: "The crossing of Beresina by Napoleon's troops". While Fałat was responsible for the construction of a suitable building in Berlin and the technical preparations, Kossak travelled to Lithuania "to acquaint himself with the banks of the Beresina" together with the painters Michał Gorstkin Wywiórski (1861-1926) and Kazimierz Pułaski (1861-1947)[12], a cousin of Kossak. From the War Ministry in Vienna he brought large amounts of literature to study the historical basis.

The chapter on "Berlin" in Kossak's "Memoirs", which begins with the work on this panorama, covers a period of seven years and comprises 35 pages of the book. Kossak himself describes this section of his life as perhaps the most interesting.[13] Probably because of the hostile reactions from Poland, it was the author's special wish to publish the memoirs during his lifetime in order to be able to personally counter any "accusation of lies or even an excess of fantasy" (p. 93 f.).

The building for the panorama painting was erected not far from the Teltow Canal in Herwarthstraße in the Berlin suburb of Lichterfelde opposite the building of the Imperial General Staff. A scaffolding and ovens were erected inside. On four large canvases, corresponding to the points of the compass, Fałat applied the colours of the landscapes according to the position of the sun, and then travelled to Krakow because he had been appointed director of the School of Fine Arts/Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych as successor to the late Jan Matejko (1838-1893). Wywiórski transferred the snow landscapes designed in watercolours by Fałat to the canvases, while Kossak, supported by Pułaski, designed and executed the figurative compositions.

In the winter of 1895, Fałat suddenly appeared in a gala suit and announced the visit of the imperial couple, who shortly afterwards appeared in the company of officers and court ladies. Kossak, utterly unprepared and clothed in a garment smeared with paint, felt compelled to greet the Emperor and expound on the battle composition (Fig. 4). The latter, obviously impressed by the artistic work, recalled not only a painting by Kossak that he had seen in the art trade, but also his military scene hanging in the Emperor of Austria's Lainzer study. Kossak's controversial opinions on the historical details of the Battle of Beresina and the role of the Polish cavalry corps, which were actually a serious violation of etiquette, were received favourably by the monarch, who thereby acknowledged the artist's honesty.

As a result, the Emperor visited the city more frequently to examine the progress of the panorama painting and finally expressed the wish that Kossak, who intended to return to Poland immediately after completion, stay in Berlin. After the Emperor had talked about the panorama painting at court dinners and diplomatic receptions, visitors from Berlin society and the diplomatic corps crowded into the panorama building. In particular, members of the Austrian, Russian and French legations wanted to find out whether the role of their respective countries in the painting of the battle corresponded with their own ideas (p. 95-108).

Wilhelm II subsequently ordered "a whole series of larger battle compositions" from Kossak on battles between Prussia and France during the Seven Years War and the liberation wars of Prussia and Russia against Napoleonic domination in Europe (p. 108). He received his first commission, a painting depicting Napoleon's victory over the Prussian marshal Gebhard von Blücher and the corps of the Russian general Sachar Olsufiew at Champaubert, (Kossak's later "Battle of Étoges/Bitwa pod Étoges" (1898, Fig. 5)[14], by letter during a family stay in Zakopane, immediately after he had completed the Beresina Panorama. Kossak again returned to the study of historical literature and finally travelled to Paris to cycle from Château-Thierry along the route that Napoleon had travelled some forty kilometres to Étoges, in order to view the scenes of the battle (p. 111). Once Kossak had returned to Berlin to draw a sketch of the painting, he informed the Emperor, who visited the painter in his studio in Charlottenburg alongside the Empress, his younger brother, Prince Henry of Prussia, and his wife, adjutants and court ladies. The party talked not only about the commissioned design, but also about Kossak's completed paintings, which were exhibited in the studio and showed battle scenes between the Polish army and Russian troops during the November Uprising of 1830/31 (p. 114-119).

Kossak does not go any further into other paintings commissioned by Wilhelm II, nor into his monumental painting "The Battle of Zorndorf" (1899), for which he was commissioned in March 1898 while he was still working on the "Battle of Étoges".[15] In order to fulfil the new commissions, the Emperor provided the painter with a studio not far from the city palace, "a magnificent, huge hall in Frederick the Great's palace, 'Monbijou'" (p. 114). Monbijou Castle on the northern bank of the Spree served as the Hohenzollern Museum from 1877. In the following five years, Kossak painted two equestrian portraits of the Emperor and six battle paintings in this studio.[16]

In the section entitled "A Dinner at the Court", Kossak writes that "the Emperor's benevolence and grace grew every week with each new picture painted for him; and his visits to my studio became more and more frequent" (p. 120). The expression of this "benevolence" was an invitation to dinner at the City Palace, where, apart from the imperial couple and Kossak, only court ladies and aides were present. The discussion at the table revolved around the battle painters of the time, Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891) and Adolph von Menzel (1815-1905), who were highly esteemed by the Emperor, and the - in the Emperor's opinion - wrong-headed purchasing policy of the director of the Berlin National Gallery, Hugo von Tschudi (1851-1911), who preferred the French Impressionists, Munch and Hodler (p. 125). In the smoking room, over liqueurs and cigars, Kossak observed the Emperor as an interested and inquisitive conversationalist, who was also able to discuss music in Europe. Finally, he took Kossak on a tour around the "Polish Chambers" in the city palace, which had been created in the 18th century for the stay of the Saxon-Polish kings, Frederick Augustus the Strong and Augustus III (p. 126). Finally, Kossak tells of the evening gatherings of Princess Marie of Radziwiłł (1840-1915), née Comtesse de Castellane, in the palace of her husband, Prince Antoni Wilhelm Radziwiłł (1833-1904), a confidant of Wilhelm I, at Pariser Platz, which were also attended by the Emperor (p. 127 f.).

The chapter on "Zakopane" (p. 131-150), depicting Kossak's first stays in his holiday resort between 1880 and 1935, describes the place and the High Tatras as a pristine world around 1880. It had never really been occupied by the partitioning powers of Russia and Austria and, apart from a few writers and painters, had also been unknown to many Poles. Kossak tells of an unspoilt, rugged mountain world that could only be explored by local guides, with a population that persisted in ancient traditions, and few holidaymakers, some of whom had travelled from far away. His detailed description of his mountain hikes explains the fascination of numerous Polish painters[17] for the Tatra landscape and the culture of the native population of the Gorals. Kossak himself was obviously only sporadically interested in these motifs in his painting.[18] In 1886 Zakopane was granted the status of a health resort, and hotels and boarding houses were built. In 1899 the town was connected to the railway.

Back in Berlin, Kossak was invited by the Emperor to attend the annual recruits' swearing-in ceremony of the guards regiments in autumn. He took part in the ceremony wearing an Austrian Ulan uniform, as he would in future do at all official occasions and receptions. As in the years that followed, as a member of the Austrian legation he attended the annual reception in the city palace, the "Schleppcour", at which all high-ranking personalities had to present themselves to the imperial couple individually, (p. 153-160).

The following chapter, "The Return of the Imperial Couple from Palestine" (p. 163-170), follows Kossak's acquisition of the studio in Monbijou Castle in 1898. From October to November of that year, William II and his wife had travelled to Palestine, part of the Ottoman Empire, consecrated the German Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem and visited the cities of Haifa, Jaffa, Beirut and Istanbul. Immediately after the reception of the imperial couple at the Brandenburg Gate and still in gala uniform, Wilhelm II visited Kossak, who had been looking forward to the reunion with his "sublime and powerful patron", in his studio: "This was a proof of great benevolence and sympathy, since several other painters and sculptors were working on imperial commissions in Berlin at the same time as I was: Begas, Rocholl, Röchling, Koner, Walter Schott etc." (p. 163-165) The Emperor gave Kossak a detailed account of his experiences in the Orient.

The painting "The Battle of Zorndorf" was not yet finished in the spring of 1899 because Kossak's father's illness and death had prevented its completion. Thereupon, Wilhelm made a personal appeal to Anton von Werner (1843-1915), chairman of the jury of the Great Berlin Art Exhibition and director of the Royal Academy of Arts, to ensure that the monumental painting could nonetheless be submitted to the exhibition later (p. 168-170); it was then exhibited there from May to September that year.[19]

Around 1900 the first problems for Kossak's stay in Berlin became apparent. The increasing phenomenon of "Hakatism",[20] synonymous with a growing hostility towards Poland in Prussia, and the criminal trial against Polish citizens after the school strike in Wreschen, made it impossible for Kossak to continue his stay in the Prussian capital. Despite his overtly Polish nationality and his Austrian uniform, he had never experienced any problems in Berlin, but "every trip to Poznan", he writes in the section entitled "Wreschen" (p. 170-172), "led him into an atmosphere of growing conflicts and national agitation". Kossak took the constructional changes in Monbijou Castle and the necessary abandonment of the studio as an opportunity to ask the Imperial Chancellery to allow him to complete the outstanding paintings in his studio in Krakow. However, the commander of the imperial headquarters, Hans von Plessen (1841-1929), saw through the pretext and rejected the request in the following words: "In any event, as a Pole, you should remain at your post more than ever. You can serve your compatriots much better here than if you were to leave."

In August 1900 Kossak received a court telegram from the Emperor ordering him to travel to Naples, from where he was to go to China as a war painter in the staff of Field Marshal Alfred Graf von Waldersee (1832-1904). On 27th July, an international expeditionary corps had left Bremerhaven to quell the Boxer Rebellion in China. Kossak had just signed a contract for a panorama of the "Battle of the Pyramids" and wanted to travel to Egypt to prepare it. At the last moment, he succeeded in averting the assignment thanks to a personal conversation with the emperor during a cavalry inspection in Altengrabow, to which he had also been ordered. The battle painter Theodor Rocholl (1854-1933) travelled to China in his place (p. 172-175).

Kossak then accepted another commission, that of a consortium founded in Warsaw to create a new panorama showing the Battle of Somosierra on 30th November 1808, as Kossak reports in the eponymous chapter. Other national-Polish subjects had previously been ruled out because they would not have passed the Prussian censorship. On the other hand, the battle of Somosierra, in which Napoleon had defeated Spanish troops on the mountain pass 60 miles north of Madrid and then fought his way to the Spanish capital with the substantial participation of Polish cavalrymen, could be considered as an innocuous topic of pan-European significance. Kossak was guaranteed a sum of 100,000 roubles for the production of the panoramic painting and the sculptural foreground terrain. It is interesting to note that in the general context of battle painting, Kossak admitted that previous paintings on this theme by French and Polish painters like Vernet, Suchodolski, his father and himself had been pure "fantasy creations" in terms of the landscape and the battle terrain. For the new panorama, however, it would have been essential to create as faithful a representation as possible. In this case also, Kossak not only studied historical literature, but also consulted a proven military historian, the Russian infantry general Aleksandr Puzyriewski (1845-1904) (p. 179-181), who came from Lithuania.

After taking a holiday with the Emperor, Kossak and his colleague Wywiórski travelled by train via Paris, Bordeaux and Madrid to Segovia, then on to the Castilian foothills in an "omnibus" pulled by mules. From there they travelled on foot to the mountain pass in question equipped with permits from the Austrian embassy, a local guide and a two-wheeled cart pulled by mules, carrying painting utensils and photographic equipment. The author describes in detail the battlefield and other geographical details known from the historical writings. These were captured by the painters in sketches and photographs (p. 181-202), including the associated troop formations.

Despite the Emperor's benevolent assessment of the first drafts created in Monbijou Castle, the Somosierra panorama was threatened with remaining unfulfilled. Kossak travelled to Warsaw with four sketches on a scale of 1:10, where the work was approved by the consortium and the military historian Puzyriewski. The latter agreed to work with the Russian Governor General of Warsaw, Alexander Imeretynski (1837-1900), to exhibit the future panorama in Warsaw. But Imeretinski refused, as he apparently feared nationalist Polish riots, as can be read between the lines in the chapter entitled "Prince Imeretynski and Grand Duke Vladimir" (p. 205-217). In view of the financial loss incurred by the Panorama building that had already been rented in Warsaw, and the canvas ordered in Brussels, Kossak appealed for mediation to Wilhelm II, who in turn contacted Grand Duke Vladimir Romanov, son of Tsar Alexander II, the man responsible for artistic affairs in Russia. Finally Kossak himself travelled with his designs to St. Petersburg to lend emphasis to the Emperor's despatch. But not even Grand Duke Vladimir was able to persuade Imeretynski to change his mind. In the meantime, in Berlin Kossak had completed the "Battle of Zorndorf" and a portrait of the Emperor on horseback, for which he was personally awarded the Order of the Red Eagle by the Emperor, after having received the Order of the Royal Crown six months earlier (p. 208).

Kossak dedicates three chapters totalling 45 pages, "Stuttgart – Kaisermanöver – Franz Joseph I. in Berlin", "Stettin" und "Des Kaisers ‚Rache‘", to his participation in manoeuvres of the Prussian army under the leadership of Wilhelm II. Due to his membership in the Austrian army he held the title of a "military attaché of foreign powers". As a guest of the Emperor he had a court equipage, a service horse and an orderly at his disposal, stayed in the best hotels and participated in the meals of the diplomatic corps (p. 219 f.). Foreign officers and diplomats were admitted to the manoeuvres as observers, but excluded from the demonstration of new means of transport and guns. On the battlefield he was regularly summoned to the Emperor (" Herr von Kossak, please report to his Majesty") in order to view particularly "picturesque" battle orders from his vantage point (p. 224).

His participation in a manoeuvre at the beginning of September 1899 in the Stuttgart, Metz and Karlsruhe area, his presence at a court ball held by the King of Württemberg in his Stuttgart residence, at an inspection of the King's Ulan forces in Hanover in the entourage of the Emperor (p. 231f.), at the visit of Emperor Franz Joseph I to Berlin on 4th May 1900 as President of the Association of Reserve Officers of the Austro-Hungarian Army (p. 233-238), at the imperial manoeuvres near Stettin in the retinue of the Austrian heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand (p. 246), at a manoeuvre in Altengrabow in the Jerichower Land east of Magdeburg (p. 251), at parades on the Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin (p. 256) and finally at the inauguration of an officers' casino in Langfuhr near Gdansk, for which Kossak had produced three paintings (p. 260), demonstrate in vivid detail his military and equestrian knowledge, his adept dealings with officers and diplomats, but above all his close connection to Emperor Wilhelm II and the Austrian imperial family. While his participation in manoeuvres was initially due to the task of producing portraits of the Emperor on horseback (Fig. 6) (p. 251), Kossak soon became part of the usual military entourage of the monarch, as the author also revealed in his anecdotes ("The Emperor's Revenge", p. 251-262).

Since the Somosierra panorama could not be created because of the intervention of Prince Imeretynski, Kossak and the Warsaw Panorama Consortium opted for a new theme, the "Battle of the Pyramids" from Napoleon's Egypt campaign in July 1798. In the corresponding month, July 1900, Kossak travelled with Wywiórski to the original site in Egypt, because the weather and lighting conditions should also correspond to the historical facts. They travelled across the Mediterranean from Trieste to Alexandria on a passenger ship belonging to Austrian Lloyd, and from there by train to Cairo (p. 265-271). Kossak was received by Prince Muhammad Ali (1875-1955, Fig. 7), the son of the former Ottoman Khedive of Egypt, who introduced him to the director of the war archives and accompanied him to the battlefields of Embabeh and Giza (p. 271-273). That said, two motifs shown in the book of Kossak's later Panorama, a gun emplacement of the Napoleonic infantry (p. 277) and an attack of the Mamluk army (p. 278) under the leadership of Murad Bey Muhammad show hardly any of the typical elements of the country.

"The end of my life in Berlin was approaching," wrote Kossak in one of the last chapters of his "Memoirs". "At the height of my success, in full possession of imperial patronage and the recognition of Berlin's circles of art lovers, I was to leave this city" (p. 283). As a member of the aristocratic Union Club, which specialised in horse racing, he had close ties to the German nobility in Poland. According to Kossak, this clientele was also affected by the anti-Polish agitation of the Hakatists and the restrictive measures of the Prussian government. On the occasion of a feast of the Order of St John at Marienburg in June 1902, to which Kossak had been invited, but had not appeared "in anticipation of what was to come", the Emperor made a speech, according to Kossak, "personally against the Slavic Front" (p. 286). This incident fuelled his decision to turn his back on Berlin immediately and forever. He accepted an invitation from the Emperor to visit the Guard Cavalry at Tempelhofer Feld, during which Wilhelm advised him of extensive commissions for paintings, including a portrait of the Empress on horseback. As Kossak sums up, "this list of large works ordered en masse was an attempt to "hold back the painter in Berlin while there was still time". (p. 293)

Back home, Kossak received telegrams from Poland criticising his alleged participation in the St John's festival at the Marienburg, as well as a message from his brother Stefan, requesting him to correct corresponding reports in the Polish press. Kossak telegraphed the newspapers in Poland that he had not been to Marienburg and explained to his brother that he had decided to leave Berlin because of the intolerable situation (p. 293 f.). A visit by the imperial couple to his studio in Monbijou Castle, where Wilhelm sat for a portrait of himself on horseback, took place in a tense atmosphere: "While I thanked and accompanied their majesties to the park gate, I was totally aware that I would never again find such a powerful and benevolent patron of my art in my life". Wilhelm, who had no knowledge of Kossak's final farewell, wished the painter a swift return from his holidays. The following day the entire telegram to Kossak's brother, who had given it to the press in Lemberg, was published in the Berlin newspapers (p. 294-296). Kossak had the commander of Plessen convey his gratitude to the Emperor and explained that he had "lost his moral peace as a result of the latest political events ..." that "my conscience is in doubt as to whether I, as a Pole, may now continue to work here" (p. 297). Kossak used his last week in Berlin to complete painting commissions and settle some personal matters.

Kossak's return to Krakow and his stays in Vienna in 1903/04 and London in 1905-07 remain unmentioned in the "Memoirs". The only episode described by the author in the penultimate chapter (p. 303-316) is the preparation and implementation of the celebration of the sixtieth anniversary of the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph I on 12th June 1908 in Vienna. After the murder of the governor of Galicia, Andrzej Kazimierz Potocki (1861-1908), on 12th April in Lviv, the Galician associations had cancelled the Polish contribution to the historical section of the procession. Only two ethnographically motivated groups were to represent Poland, a "Krakow Wedding", prepared by the painters Henryk Uziemblo (1879-1949) and Włodzimierz Tetmajer (1861-1923), and a "Section of Masurian Horsemen", designed by Kossak (p. 304). However, when the Vienna Festival Committee planned to include a group on the history of Polish King Johann III Sobieski in the historical part of the train, Kossak was asked by the Galician side to travel to Vienna, supervise the preparation of the costumes (p. 306 f.) and finally lead the Polish section in the role of King John on horseback (Fig. 8). Kossak vividly reports on the design of the decorations, a failed intrigue to banish the Polish group to the end of the march, and the festive procession past the Emperor on the Vienna Opera Ring (p. 308-315).

IIn a concluding chapter devoid of any internal context and exact dating, Kossak tells of his participation in a cavalry manoeuvre in the Galician village of Chłopy (now Peremoschne) near Komarno (now in the Rajon Horodok/Ukraine) not far from Lemberg (now Lviv), which Emperor Franz Josef I had presumably held in September 1907 with fourteen thousand men (p. 319).[22] The Emperor took up his quarters in the castle of Count Karol de Brzezie Lanckoroński (1848-1933). The aged monarch greeted Kossak personally and was sufficiently informed about his departure from Berlin (p. 321). The painter returned the favour with a series of water-colour menu cards depicting humorous scenes "from military and camp life", which he produced daily for the Emperor (p. 322). In this chapter there are also richly illustrated descriptions of the riders and horses involved in manoeuvres which culminate in eulogies of the Polish cavalry that Kossak puts into the mouths of Austrian and Prussian officers (p. 324). It concludes with a letter from the adjutant of Emperor Wilhelm II, later General August von Mackensen (1849-1945), which reached Kossak in Chłopy and in which he praised Kossak's painting in the Berlin City Palace, "The Grenadiers at Château-Thierry": "His Majesty shared my delight ... Will this be your last brushstroke to the glory of Prussian military feats? (p. 326)

Anyone expecting Kossak's "Memoirs" to provide them with far-reaching information about individual paintings, his style of painting or contemporary art trends will be disappointed. Individual references to the production technique used in the commercially marketed battle panoramas, to Kossak's efforts to reproduce the scenes depicted in the panoramas and battle paintings historically and faithfully by studying literature and travelling to the original locations, as well as the monarch's constant supervision of the works, are, however, valuable for the history of history painting. All in all, however, Kossak places his military duties and experiences, and his close connections to contemporary monarchs, aristocrats and officers, in the foreground: "Fate has granted me the privilege of entering interesting circles and situations as a result of my work". The affirmations of his Polish origin and his love for his homeland, which were intended to correct the negative image he had created in Poland, are reinforced by his desire to live and work in his homeland in the future (p. 330). A photograph taken in front of the entrance to his studio in Zakopane completes the "Memoirs" (Fig. 9).

Axel Feuß, April 2019